Ever since Donald Trump signed an executive order in February directing the US Commerce Department to examine whether there should be tariffs on copper, copper producers and traders have been expecting and pricing in their likelihood.

For months, US copper futures have traded at big premiums – as much as $US1300 a tonne – to their London counterparts as traders scrambled to ship physical copper from warehouses in London and Shanghai to the US to front-run the tariffs. The increased US price for copper has been flowing into the cost bases of US manufacturers.

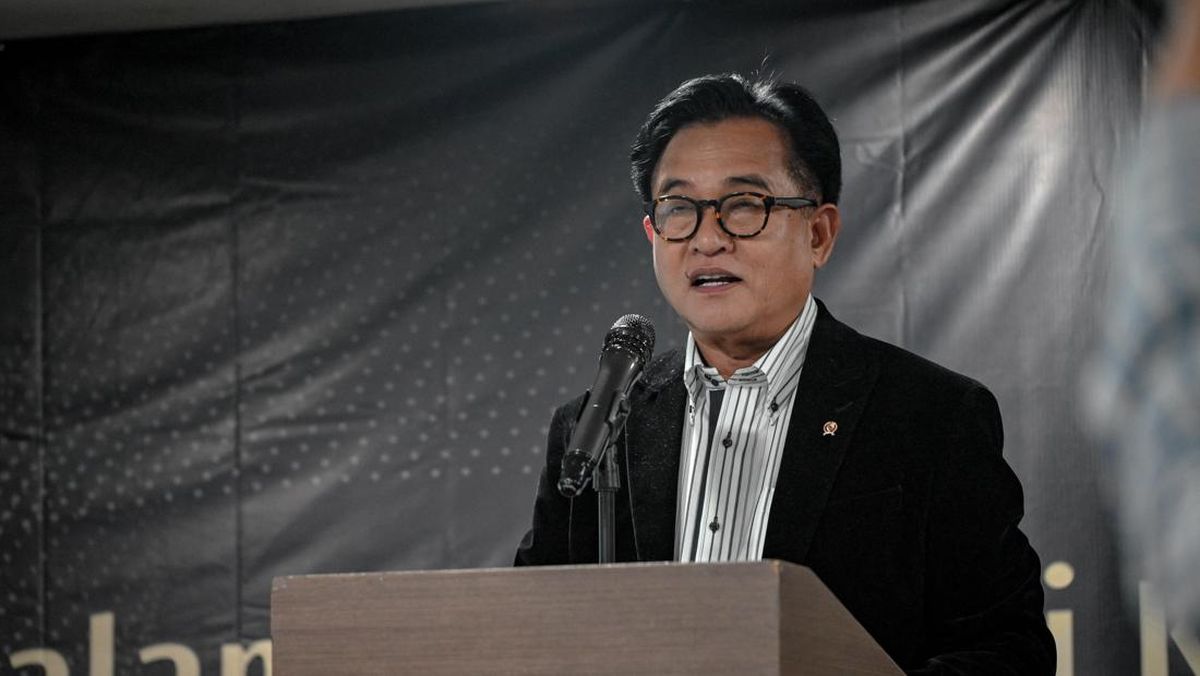

President Donald Trump has said he plans to impose a 50 per cent tariff on US copper imports.Credit: AP

The buyers and traders of the metal had expected the tariff rate to be somewhere between 10 per cent and 25 per cent.

On Tuesday, however, Trump, having received the Commerce Department report, announced there’d be a 50 per cent tariff on copper – the same level as those on steel and aluminium imports – in place by the end of this month. US copper futures, already elevated, spiked dramatically, with prices jumping as much as 17 per cent.

Trump is using national security grounds and Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act to effect the tariffs, which haven’t been subjected to the legal challenges that his base and reciprocal tariffs have faced. The administration is appealing a US Court of International Trade decision that those latter tariffs are illegal.

Unlike most of Trump’s tariffs, based bizarrely on US trade deficits with other countries, a national security case can be made for copper, arguably among the most strategic of commodities.

Loading

It’s vital for modern infrastructure and manufacturers, with demand exploding for its use in “green” technologies as electrification accelerates globally. The data centres that will be built to support artificial intelligence will alone consume enormous amounts of electricity and require huge volumes of copper.

Even as demand for the metal soars, new supply is under pressure. Existing orebodies are being depleted, their grades are diminishing and there are only a handful of large new projects on drawing boards globally. BHP has forecast a deficit – more demand than available supply – in the copper market within a decade.

The US has substantial reserves and resources of unmined copper, but produced about half the 1.64 million tonnes that it consumed last year. It gained another 150,000 or so tonnes from recycling but imported 810,000 tonnes of the refined metal.

The challenge for the US is that it has copper in the ground, but its smelting and refining capacity has shrunk over the past several decades.

A slump in the copper price in the 1980s and 1990s led to the closure of US mines and smelters. In the late 1990s it still had 11 smelters in operation; today it has two, with a third that processes scrap.

By contrast, China, which saw a strategic opportunity in the 1990s, made major investments in smelting and now has more than half the world’s smelting capacity. Ore from the rest of the world is exported to China to be smelted and refined and then either increasingly consumed within China – which is leading the global electrification race – or re-exported.

Given the centrality of copper to the 21st-century economy and advanced industrial and military technologies, China’s dominance of the sector is obviously seen by the US as a national security threat.

The obvious response would be to produce and process more of its own copper. The problem it has is that most of its undeveloped resources are on federal land, which creates challenging and lengthy approval processes. The average time to bring a new US mine into operation has blown out to about 29 years.

The giant Resolution Copper project in Arizona owned by Rio Tinto and BHP, for instance, was discovered in 1995.

The Resolution Copper mine in Arizona.Credit: Darryl Webb

Rio submitted a mine plan for the project, in which the companies have already invested several billion dollars, in 2013. It took until May this year for the US Supreme Court to clear the way for a land swap, opposed by native Americans, that will enable the project to proceed. It will take a decade or more to bring a mine into production.

BHP and Rio, via the giant Escondida mine in Chile, will, incidentally, be exposed to the copper tariff, although more of that project’s output is exported to Asia. Rio does have a mine – and a smelter – in the US that might benefit from the tariff and the higher domestic copper prices it will produce.

Adding more domestic supply of copper might address the threat of supply shortages and the increasing reliance on Latin America (although the US has a free trade agreement with Chile, the major producer), but it doesn’t solve the processing capacity shortage.

Loading

Smelters take at least a decade and $US3 billion-plus of investment to construct and involve environmentally unfriendly processes, which is part of the explanation for why much of the global capacity migrated to China which, at the time, was more interested in economic and strategic benefits than its environment.

Even if that capacity could be built in the US, it is unlikely to be competitive with China’s smelters. China already has about eight of the world’s 20 largest copper smelters.

Meanwhile, with the likelihood that Trump’s new tariff will apply not only to imports of refined copper but downstream semi-fabricated products like copper sheeting and wire, US manufacturers reliant on copper will face a steep increase in costs.

America’s reliance on imported copper, once the tariff is in place, means that those manufacturers will not only incur higher costs that they will try to pass onto their own customers, but those costs will be unique to the US. Therefore, they will, to the extent that they compete outside the US or with imports, be at a significant competitive disadvantage.

The ubiquity of copper usage means that it would be an economy-wide issue, adding to inflation while damaging US competitiveness. That’s a familiar aspect of Trump’s trade war against the rest of the world.

US copper buyers have already seen a preview of what’s to come in the differential in US copper prices and those in the rest of the world as traders scrambled to get ahead of the tariffs.

That rush to get their hands on physical metal has not only forced the copper price to record levels, but has inverted the normal futures price curve for copper, known as contango, where future prices are higher than the spot price to reflect the costs of storage, opportunity costs and risk.

The price curve is now in “backwardation” – spot prices are higher than future prices, with the prospect of losses for traders and hedged sellers of copper as their contracts expire and they are forced to cover their exposures at higher prices.

The shortage of physical metal in the market, driven by the urgency of getting ahead of the tariff, could lead to even more price rises and market disruption as sellers that have to deliver physical copper try to cover their positions.

Trump has claimed that “trade wars are good and easy to win”. With copper, as with all of his other tariffs, he’ll discover that they are nowhere near as straightforward as he has assumed, with hosts of unexpected and unintended consequences, some of them unpleasant and peculiarly so, not just for copper buyers and traders, but for US manufacturers and their customers.

The Business Briefing newsletter delivers major stories, exclusive coverage and expert opinion. Sign up to get it every weekday morning.

Most Viewed in Business

Loading