Former RBA economist, and now HSBC Australia chief economist, Paul Bloxham was polite in describing the Reserve Bank’s communication as “quite choppy”.

Loading

“In February, the board appeared dovish and cut. In April, it was hawkish and held steady. In May, there was a dovish cut – with talk of a possible 50 basis point being discussed – while Tuesday’s event was comparatively hawkish,” he noted.

According to Bullock, the decision to hold was made largely because the bank wants to see the June quarter inflation figures due on July 30.

While the bank focuses on the quarterly inflation figures, the Australian Bureau of Statistics has been producing a monthly inflation report since the second half of 2022.

Monthly inflation, both headline and underlying, have been tracking lower than the quarterly figures for some time. But there are doubts over the accuracy of the monthly numbers, hence Bullock’s commentary about the importance of the July 30 numbers.

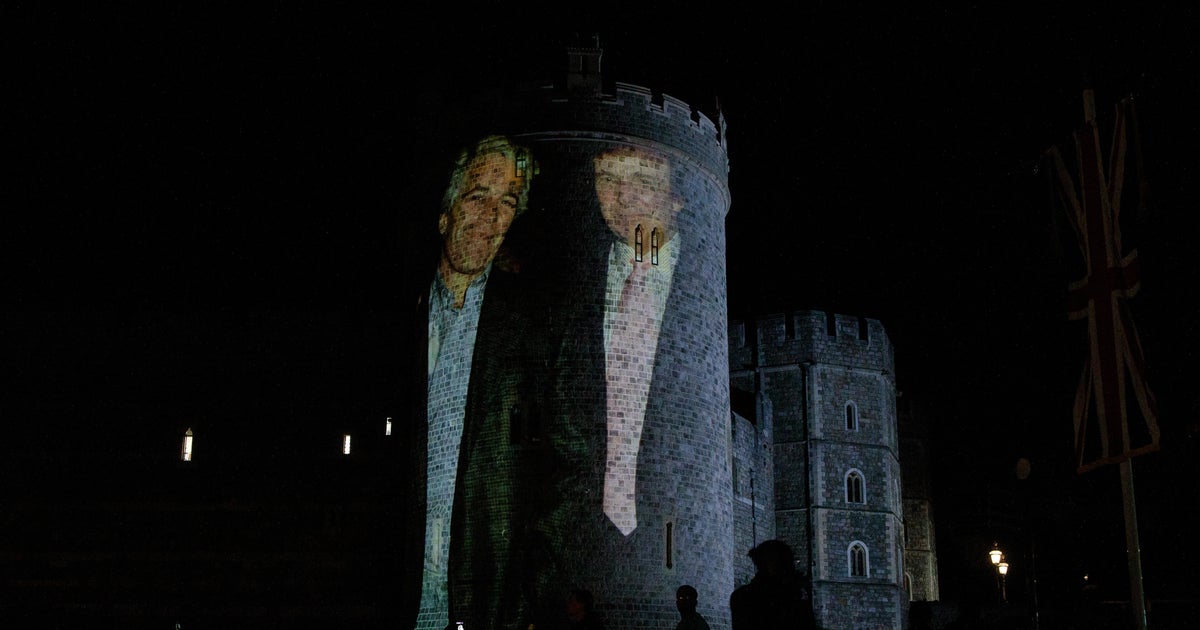

However, financial markets and economists believe the monthly numbers are giving a solid signal about overall inflation. The same markets and economists have also been influenced by other figures (such as recent poor retail trade data) and the turmoil in the global economy stemming from the Trump administration.

Donald Trump’s tariff plans are a key source of uncertainty.Credit: Bloomberg

The monthly inflation numbers were released on June 26. Before those figures, markets put the chance of a rate cut in July at more than 80 per cent. After the figures, the rate cut was fully baked in.

It was also when prominent economists, including former RBA senior economist Luci Ellis, started to change their call on the July meeting outcome. The economics team of every big bank in the country predicted a July rate cut.

Many of the questions put to Bullock at her press conference on Tuesday centred on how the RBA knew market expectations were at fever-pitch for a rate cut, but the Reserve did nothing to curb that enthusiasm.

Loading

Previously, if the bank believed markets and economists were getting too excited about a particular meeting’s outcome, it may have dropped a quiet line to a prominent commentator. More recently, they have put a line or two into a speech to signal the bank’s intentions.

Most famously, Phil Lowe used a speech in 2019 to say the bank would consider a rate cut at its next meeting.

Bullock argued that bank staff do “lots of speeches” to explain the Reserve’s thinking.

Between its May meeting and this week’s, there were three speeches by senior staff: one about the bond market (made on June 12 in Tokyo); deputy governor Andrew Hauser gave his reflections on China and tariffs in late May; while chief economist Sarah Hunter gave an address on June 3.

Hunter’s address focused heavily on the current global uncertainty, arguing that economic growth, the jobs market and inflation would likely be a little softer than expected.

That was three weeks before the monthly inflation numbers and the last public utterance by a senior bank official before Bullock’s press conference.

Another element of the decision was the way Bullock set the scene for a rate cut when the Reserve next meets in mid-August.

Since taking over from Lowe, who came under fire for signalling the bank would hold rates steady until 2024, Bullock has gone out of her way to say she would not give “forward guidance” on future rate movements.

But both her and the board used comments such as “wait for a little more information” or that rate cuts are now “timing rather than direction”. That’s forward guidance.

Whether an interest rate cut this week or one on August 12 matters all that much to the economy is debatable. But what is not debatable is that investors with hundreds of millions dollars sunk in financial instruments, and millions of people with a mortgage, believed there would be a rate cut on Tuesday.

Loading

Then there were the business owners who had hoped for a cut to loosen the nation’s purse strings. Lower borrowing costs could entice those business operators to investment in productivity-enhancing equipment that would help the economy’s long-term performance.

Deloitte Access Economics’ lead partner Pradeep Philip noted that given the ongoing global turmoil afflicting the domestic economy, the Reserve had made a misstep.

“In light of continuing sluggish economic growth and the increase in global instability, a rate cut would have been seen as taking out insurance for the Australian economy,” he said.

“Both monetary and fiscal policy needs to be focused on the supply constraints and run rate of the economy.”

Cut through the noise of federal politics with news, views and expert analysis. Subscribers can sign up to our weekly Inside Politics newsletter.