When the time finally came to decide, expanding marriage to include same-sex couples was the easiest big thing Australia has ever done. There was a lot of angst and soul-searching and politicking to reach that point and of course, not everyone agreed, but for many, it came down to a simple consideration.

Nearly all of us have gay people in our lives, whether they are family, friends, neighbours or work colleagues. We want them to be happy. If enabling them to marry the person they love would do this, who were we to block the aisle? It was a transaction that cost us nothing and offered something to people we care about.

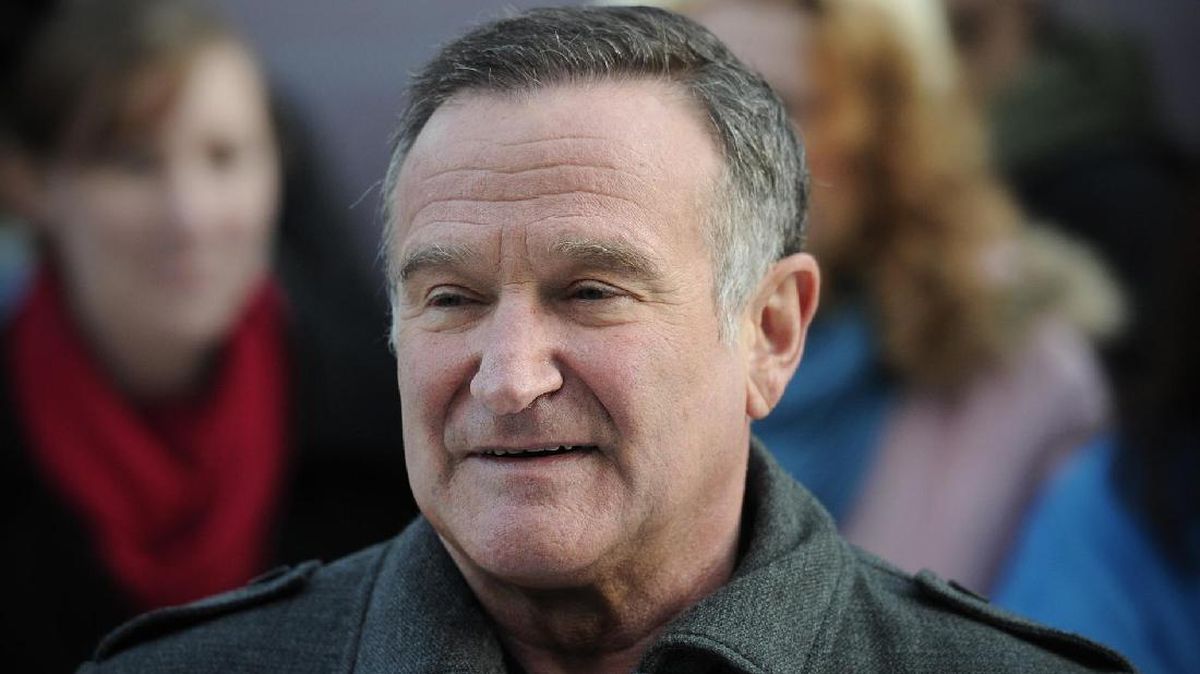

Gunditjmara and Bunganditj elder Uncle Johnny Lovett.Credit: Justin McManus.

Five years after the Marriage Law Postal Survey was carried in all states and territories we voted again, this time at a referendum. The question put to us was whether “to alter the Constitution to recognise the First Peoples of Australia by establishing an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice”.

As with gay marriage, we weren’t being asked to give something up. Rather, we were being asked to recognise something incontrovertible – that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were here long before whitefellas arrived – and to go give them something at no cost to us; the right to have their say when the government is making decisions that affect them.

Nearly two years on from that vote, there are plenty of reasons proffered for why the referendum failed. I suspect part of the story is the lesson of the gay marriage survey.

Most of us don’t have Aboriginal people as our friends or neighbours. We don’t work with them. There was an absence of empathy from us towards the people we were asked to help.

Given what we know about differences in life expectancy, rates of preventable disease and suicide, education levels, lifetime earnings, homelessness and exposure to child protection, family violence, and criminal justice systems between white and black Australia, this speaks to a shameful indifference.

There is a harder view of this, put to me by Aboriginal people who have thought about and lived this stuff in a way whitefellas can’t. Their explanation, both for the result of the 2023 referendum and decisions taken over the two and a half centuries that preceded it, is that at some level, we hate them.

It is a judgment which, if true, means that aspirations for reconciliation and closing the gap between the quality of lives experienced by Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australians are well-intentioned but futile. A more hopeful assessment of the Australian character, to borrow a phrase from an unlikely source in Donald Trump, is that when it comes to Aboriginal affairs, we “don’t know what the f---” we are doing.

Uncle Johnny and Claudette Lovett, two of 1500 First Peoples to provide evidence to Victoria’s Yoorrook Justice Commission, expressed it in more polite terms. “You can’t expect people who have never lived or never walked in the shoes of Aboriginal people to understand and get it right,” they told the commission.

All of us should borrow from the wisdom of Uncle Johnny as we contemplate the Yoorrook findings about systemic injustices against First Peoples in Victoria since European settlement and the state government and opposition frame their responses to its recommendations.

If the truth telling documented by Yoorrook and treaty negotiations currently under way between the First Peoples’ Assembly and the Allan government are going to lead to a change in script for Aboriginal people, we need to approach these matters with more seriousness than the facile debate that flared at the start of the week about whether this government is moving to legislate its own Voice to parliament.

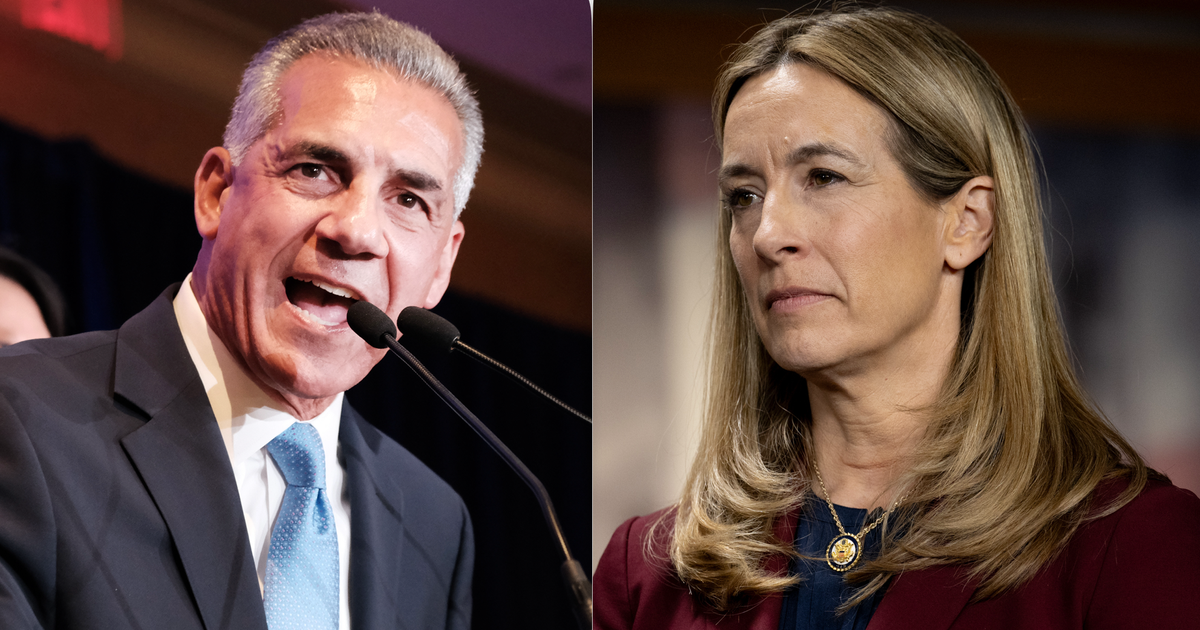

As soon as the idea of the Victorian Voice was floated, still undiscovered tribes in the Amazon knew what Brad Battin was going to say next.

Loading

The opposition leader accused Jacinta Allan, perhaps the least ideologically driven premier Victorian Labor has produced, of ignoring the will of the people (as expressed at the referendum) and more pressing concerns about cost of living and crime to pursue an ideological agenda.

From there, the flying monkeys of hot-take commentary gave voice to a dozen or so newspaper columns and Sky News op-eds, variously describing it as a slap in the face to Victorian voters and an affront to democracy.

All of which misses the point of what Yoorrook and Victoria’s treaty process are about.

The Yoorrook commissioners don’t want a Voice, a body conceived as a First Peoples’ advisory committee to federal parliament. They want far more – a permanent body of First Peoples, underpinned by legislation, with the power to make decisions on matters that directly affect Aboriginal lives.

Recommendation 96 of 100 of their final report reads: “The Victorian government must negotiate with First Peoples the establishment of a permanent First Peoples’ representative body with powers at all levels of political and policy decision-making.” This goes well beyond consultation.

Separately, the commission floated the idea of establishing reserved seats in the Victorian parliament for First Peoples representatives and for an Aboriginal person to always serve as minister for treaty and First Peoples.

At its heart, Yoorrook is a treatise for Aboriginal self-determination. Jacinta Allan in her evidence to the commission declared her government supports and shares this ambition. It is the basis of her government’s commitment to treaty.

A very big conversation is under way in Victoria about our future relationship with Aboriginal Australia. The best part we can play in this is to say less and listen more. Either slip on the shoes of Uncle Johnny or get out of the way.

Chip Le Grand is state political editor.

The Opinion newsletter is a weekly wrap of views that will challenge, champion and inform your own. Sign up here.

Most Viewed in Politics

Loading