By Jessica Dettmann

July 3, 2025 — 5.00am

I’ve always been as besotted with the idea of living in London as I was embarrassed by being besotted with the idea of living in London. It’s such a terrible cliché: middle-class, white Australian girl grows up watching too much Press Gang, This Life and Black Books and, on finishing school, dreams of becoming an Antipodean Bridget Jones, follows the well-worn road of a gap year, moves to England, has a brilliant time and maybe never comes back. I thought for sure I would take that path.

But I kept putting it off. After my final high school exams, I was still not quite 18 and didn’t feel brave enough to go live in a strange city on my own. After university, I needed money before I could consider the move, so I found three jobs and got to work, putting off the trip for another year. The next obstacle was a boyfriend I didn’t want to break up with. That time, I even got as far as starting my year away, only to spend the first month with him in Europe before throwing in the towel on my plan to continue to London and coming home with him.

Then, back in Sydney, there was a job: a highly sought-after (by a particular subset of people with a fondness for books and extremely low salaries) entry-level position at a well-known multinational publishing house. I couldn’t say no to getting my foot in the door of such a glamorous and exciting industry, could I?

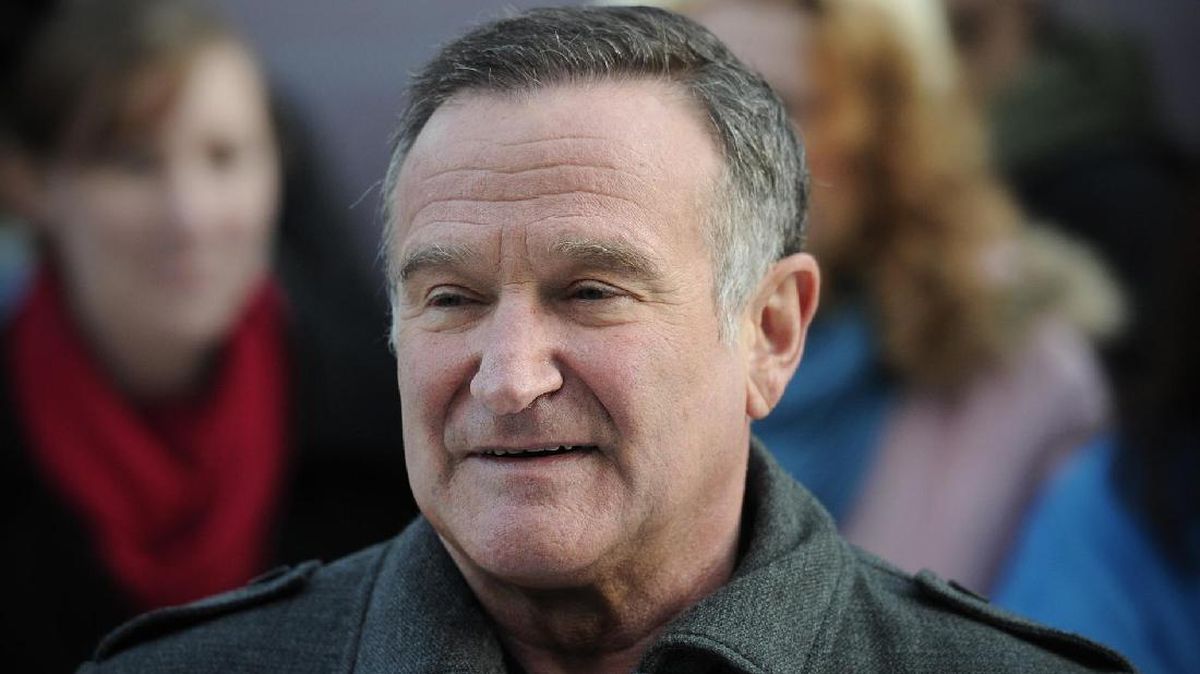

We can’t always have all of what we once wanted, but we can try to have some of it.Credit: Getty Images

You can see where this is going. For the next decade I worked away in publishing, moving up the ladder, quietly living through my 20s and watching as every year friends left for time abroad, building new lives that some returned from and some didn’t. I stopped thinking that could be me. I had a mortgage now, and a relationship, work I enjoyed, family I adored and great friends. It would be silly to throw all that away.

Before I knew it, 20 years had passed and I had a great life. I was a mother of two, happily married, living in suburban Sydney – and I had pivoted from editing to writing books for a living. Books largely set in suburban Sydney, about mothers living perfectly good lives. After three novels, I began to see a pattern emerging: all these women wanted more.

The regret I had swallowed about my permanently delayed gap year began to creep back. My world had closed up around that potential gap, leaving no great scar, but there was a tingle of discontent, like you get before a cold sore erupts.

Loading

The human propensity for dissatisfaction is what has led us to where we are today as a species. It’s why we figured out how to control fire and domesticate animals, and build shelter; what led us to strive for discovery, exploration and invention. (It’s responsible for the climate crisis and most wars, along with social media and celebrity culture – so, you know, not all good things.) It’s also pretty insufferable coming from a person of great privilege and good fortune, so I did what any writer does to try to validate their feelings: I turned it into material.

I began to consider regret and what it has to teach us. This regret about not taking a gap year has shaped me: I’m intensely curious about (read: deeply envious of) people who have moved to other countries, either briefly or permanently. I wondered if there was something in that regret that could be incorporated into my life now. Was this a sign that I wanted to uproot my family and move overseas?

Given that the logistics of living an adult life and child-rearing in the place I have always lived, with close friends and family moments away, were already almost more than I could manage, I quickly realised that no, I didn’t actually want to rent out the house, rehome the pets, find new jobs and schools and drag everyone across the world. Because I was pretty sure that if I did, I’d arrive in London only to discover that it was actually my 20-year-old self I wanted to be in London, not the same harried mother I am in Sydney, only now with lonely children and no parents to babysit them.

That regret, I began to see, was more a general sadness about no longer having my whole life ahead of me. For I am now closer in age to having a child ready to head off on a gap year than I am to the version of me who sat too long waiting for the right moment, and who I have become is probably more or less who I am going to be in this life. Unless someone invents a machine that can actually turn back time, I’ll never be a person who lived in London in their 20s. All those potential other versions of me, are they who I am mourning?

I didn’t actually want to rent out the house, rehome the pets, find new jobs and schools and drag everyone across the world.

The answer to all this middle-aged angst was staring me in the face. Yes, of course I needed to go to London, but I absolutely didn’t need to drag my family along. Instead, I would sell it to them not as a midlife crisis but as “book research” – after all, my job is creating characters and making them have adventures and learn things, and sometimes reinvent themselves. It’s not me who needs reinventing! I can stay my own trepidatious, boring self, and my characters can lead all the lives I haven’t. Fiction, both the writing and the reading, is a miraculous cure for regret.

Between my husband’s and my busy schedules of driving our children to sport and our parents to medical appointments, I managed to carve out nine days for the trip, which I spent walking the streets of London in the company of two made-up friends, Margot and Tess: one (fictionally) about my age, the other (fictionally) dead at 25 from ovarian cancer.

Tess is an English backpacker who meets Margot when they are working in a pub in inner-Sydney’s Balmain in 2000. They plan to travel back to live in London together, but when Margot falls in love in Sydney and delays the trip, it throws a spanner in the works. Tess throws an even bigger spanner in the works by dying a couple of years later, leaving Margot forever wondering what might have been. Twenty years later, when the book is set, Margot learns that Tess, before dying, left a bequest. She is sent to London to open a series of letters containing tasks for her to carry out, and thus Margot is forced to examine where she is in her life, compared to where she and Tess had thought she would be by this stage.

Loading

Through these characters and their story, I could examine all my feelings about the paths not taken, and they could lead the lives I didn’t. Through Margot, I explore how, while taking the sensible path in life can feel boring by comparison, there’s a bravery in recognising who you are, what suits you, and not simply following the crowd.

In looking honestly at my regret for not taking that gap year all those years ago, I have come to accept that it wasn’t the right thing for me, at the time. Maybe I was never destined to spend a wild year in London in the 1990s, right in the ecstasy-soaked heyday of Cool Britannia, the city by many accounts being the most fun it had been since the swinging ’60s.

Maybe my gap year was always meant to be nine days long, a melatonin-soaked trip taken when I was 44, post-global pandemic. Maybe it had to be, so I could write this book.

Your Friend and Mine (Atlantic Books) by Jessica Dettmann is out now.

Get the best of Sunday Life magazine delivered to your inbox every Sunday morning. Sign up here for our free newsletter.

Most Viewed in Lifestyle

Loading