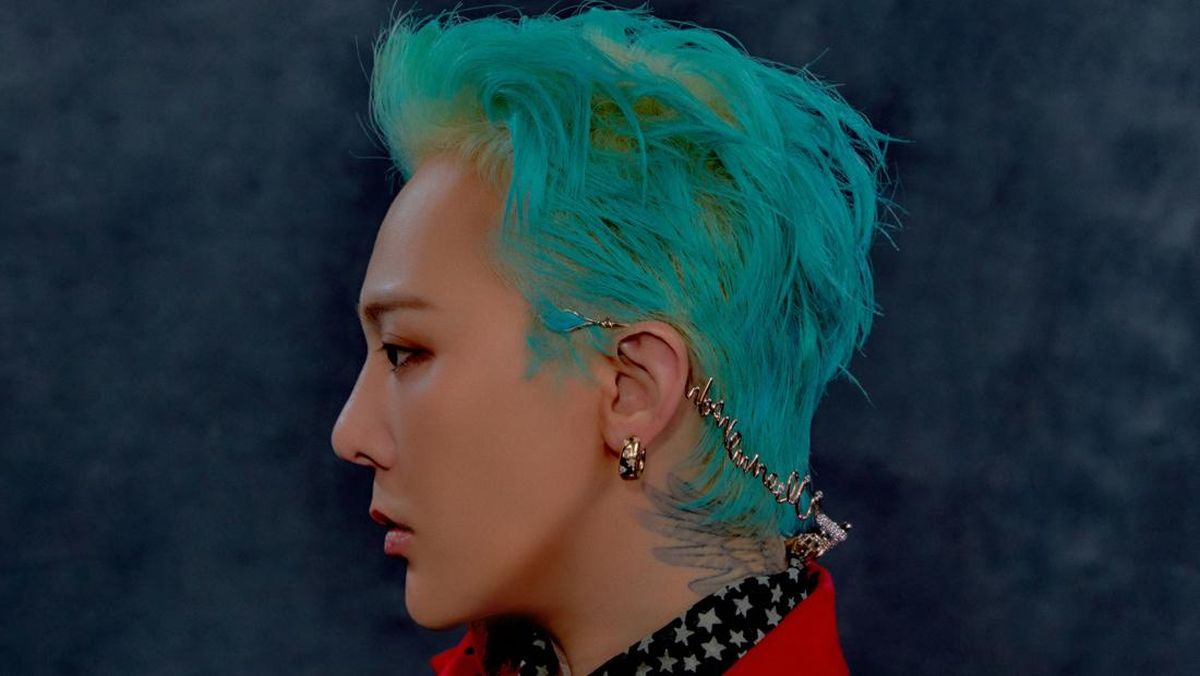

A rocking horse with its face carved into a frown. Misshapen pigs wandering the countryside. Predatory drones hunting from above. A rag doll playing dead. All are imagined and real horrors that manifest on Billy Woods’ new album. Glowering out from a thicket of dry branches on its cover, the album’s namesake boogeyman: black face, wild hair, red lips, white teeth and catatonic eyes – the golliwog.

“It’s a good word, the way it starts and ends with the same sound, the way it bounces around,” Woods says nonchalantly of choosing the racially loaded word as a jumping off point for his album. (Woods’ moniker is a pseudonym he uses, along with blurring his face in press imagery and music videos, to protect his anonymity.)

His response belies the lyrical, thematic and referential density of his work on Golliwog (a YouTube deep dive is advised). The album repurposes the often exploitative, gruesome and violent horrorcore rap subgenre as a vessel articulating the roots of the blanket dread it feels like we’re all living under. It’s part ode to late rapper MF Doom, part pyrexic political poem.

“I spent my childhood in Zimbabwe. People had the toys or the dolls, and it was not uncommon to encounter it. I’m sure there was an Enid Blyton book,” says Woods, whose father is a Zimbabwean Marxist intellectual and mother a Jamaican English literature professor.

“It’s been interesting putting out the album to a mostly American audience,” he adds. “The term and the doll has no real cultural resonance or relevance here.”

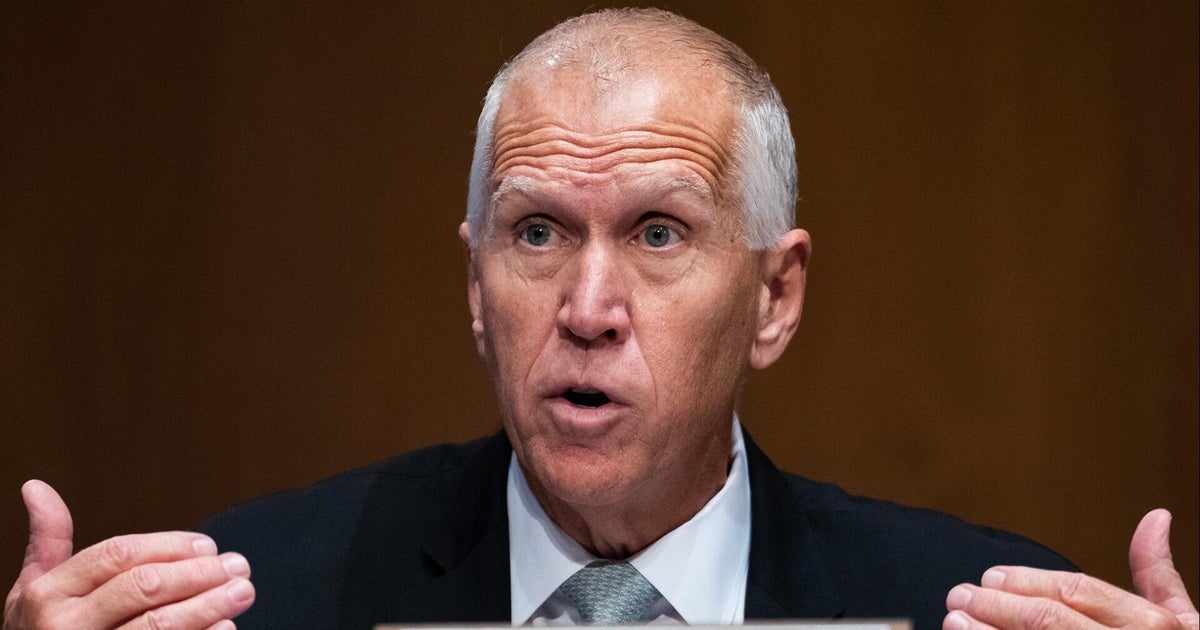

Billy Woods’ new album, Golliwog.

Created by the American cartoonist and author Florence Kate Upton, the golliwog is illustrated using racist, 19th-century blackface minstrel tropes common at the time of its invention. Cast first as a child’s friendly companion, the golliwog turned villainous when it found popularity in England and its colonies, including Australia, each with their own histories of subjugating and caricaturing black and First Nations peoples. Upton’s character had slipped her grasp and taken on a life of its own.

In Australia, golliwogs still hide in antique shops or on a relative’s mantelpiece. Golliwog is the etymological origin of the racial slur “wog”. A hot air balloon named Black Magic, nicknamed Golly, with a black face, red mouth, white eyes and a bow tie, was banned from flying in the Canberra Balloon Spectacular in 2019. One of Golly’s owners, Kay Turnbull, claimed it was never intended “to offend anyone”, “never received a complaint” and “not directed at Aboriginals or anyone that might be a different colour.” Turnbull feigned innocence, despite having already confirmed the balloon’s inspiration on the Aunty Monkey ballooning podcast in 2017.

“People end up in these situations and then take new discoveries as a threat to their childhood selves and their childhood memories: ‘I had a golliwog. I wasn’t racist. I just love this doll,’” says Woods. “The inability of them to contextualise that two things at the same time can be true, I find that battle is interesting. To see people refuse to fight that battle, or to lose it.”

Golliwog’s feverish lyrical inventiveness often casts its scares back into the realm of gallows humour. Its truly terrifying passages all come from the real world, particularly over three tracks closing its first third.

“Watched my mother cry from the top of the stairs. Scared when it came through the walls, I covered my ears … How many times I gotta tell you kids? It’s us in this room, that’s it,” raps Woods over a woman’s sobs on Waterproof Mascara, followed by his tongue-in-cheek refrain: “Don’t trust anyone!” The scene was sketched from Woods’ real-life experience of domestic violence.

“I love my father very much. He was an abusive husband. The existence of that dichotomy was one of the challenges that I was dealing with growing up,” says Woods.

‘I wanted to talk about things that make up this timeline we’re in … where you see so much but can do so little.’

On Counterclockwise, Woods articulates the present moment’s fugue state. The track samples an obscure ’70s New Zealand psych rock band, references the low-budget 2004 time travel film Primer, and samples a US official recounting the extensive torture of Abu Zubaydah – the longest-held prisoner in the US’s so-called “war on terror”, whose detention without charge at Guantanamo Bay for nearly 20 years has been broadly questioned.

Loading

“[I thought] about the techniques that were being used on people like Abu Zubaydah: sleep deprivation, noise, sensory deprivation, very small confinement in the dark,” says Woods. “Do they lose track of time? You put them in the box and then bring them out and tell them it’s been a week, or it’s only been five hours, they have no idea. What are your dreams like in that situation? Are you dreaming about your own torture? Do you dream of escaping? Is it like a waking dream? Do you wonder if your reality is even real?”

The album taps the terror of the slippage between what you know to be true and what you’re told is true: when political debates downplay climate change, or when airstrikes on Iran over alleged nuclear ambitions trigger memories of the Iraq War.

“Regardless of their political affiliations or anything, people would much rather have the history that they imagined to the actual complications of how life really is,” says Woods.

Corinthians closes the trifecta with a chest-crushing bass drop cracking open the nuances of perception. Out slip biblical references, A Scanner Darkly, The Sandman, big money, big oil and Gaza. “I wanted to talk about the things that make up this timeline that we’re in, this age where you see so much but can do so little,” says Woods.

Golliwog speaks to the adult concerns of politics and warfare, but it also uses the golliwog to explore the journey from childhood innocence into internalised adult fear states. It’s about how sometimes the scariest things are hiding in plain sight.

Woods reads me a Bible verse from 1 Corinthians 13:12: “For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part, but then shall I know even as also I am known.”

The night before my interview with Woods, the realisation that golliwogs were closer to home than a general encounter in popular culture shocked me like a jump scare at 11pm: my puppeteer mother had several golliwogs in our house. One, crudely constructed with a belted tunic and hair tied into five pigtails poking straight up in the air; another “topsy-turvy” twin doll, one white and one black, joined torso to torso. With a flip, they’d alternately disappear under their shared dress, imitating the upstairs/downstairs living arrangements of master and servant, slaver and enslaved.

Loading

Most horrifying of all, at least for me, was the one I’d hand-stitched myself, seemingly inspired by Disney’s animated Beauty and the Beast from 1991. Instead of the heroic beast’s flowing golden fur, my little monster’s white eyes and sharp teeth glared out from a jet-black face. Mum had collected the figures at a time of changing values in racial politics in ’70s New Zealand, both curious and repulsed by what they represented, but hadn’t passed on the message to me. My mother is not a racist and I wasn’t a racist child, but innocently enough I did regurgitate a racist image. Are all of these things true? Are none of them?

“People really struggle with that. They don’t want to think that the people, things, symbols that they love may actually have other bad connotations, meaning maybe that is actually their primary connotation,” says Woods. “To move back or allow any piece of that to be tarnished is just too much to take.”

Billy Woods’ Golliwog is out now.