It’s time, Sussan Ley: What Gough Whitlam can teach her about saving a lost party

In 1967, Gough Whitlam was in a strikingly similar position to Sussan Ley today. The newly installed Labor leader was little known to the public. He bore no resemblance to his unpopular predecessor. His objective was to modernise a party that had lost touch with modern Australia.

illo from Joe Benke

Whitlam came to the leadership after Labor had suffered a devastating electoral rout in 1966 – a massive landslide to Harold Holt’s coalition, in which the number of Labor MPs was reduced to half those of the government: almost exactly the same ratio as the opposition today.

When Sussan Ley gave her first big speech as opposition leader last Wednesday, Gough Whitlam was probably the furthest thing from her mind. Her speech was as un-Whitlamesque as it is possible to be: humble, self-critical, even apologetic. Frankly acknowledging that “what we as the Liberal Party presented to the Australian people was comprehensively rejected”, Ley went on to say: “We respect the election outcome with humility. We accept it with contrition.”

I doubt we’ve ever heard such honest self-appraisal from an Australian political leader. Yet, to draw a line under the worst defeat in the Liberal Party’s history, that was precisely what the occasion demanded, and Ley hit the mark.

It tells you just how far the party had drifted from the political mainstream that the very fact the speech took place at the National Press Club – second only to parliament as the customary venue for important political addresses – was itself a story. By returning to a rostrum boycotted by her predecessor, the new leader sent an unmistakable message: we’re no longer in the echo chamber; the Liberal Party is back in the game.

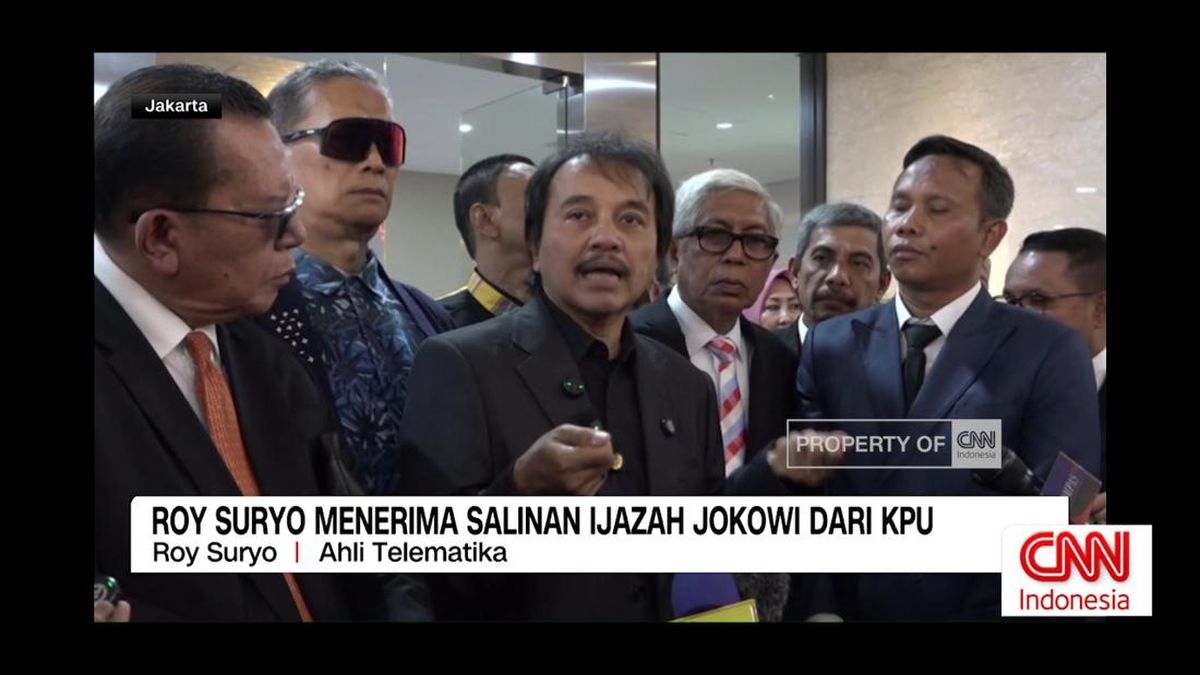

Sussan Ley at the National Press Club.Credit: Alex Ellinghausen

Ley used the speech to sketch a path forward for internal reform and future policy development.

One of the most important issues she dealt with was the party’s future approach to emissions reduction. She announced the establishment of a working group on “energy and emissions reduction” policy. Led by Dan Tehan – one of the Coalition’s most capable politicians, who was the only frontbencher to claim a ministerial scalp in the last parliament – it is tasked with developing policies that ensure a stable energy grid to provide affordable and reliable power, while reducing emissions “so that we are playing our part in the global effort”.

Ley did not specifically mention the 2050 net zero emissions target, which has been Coalition policy since 2021, although her carefully chosen language suggested no appetite to abandon it.

Nevertheless, I expect walking away from the net zero target will become the issue on which the party’s right wing will make its stand. That has already begun to happen.

Just four weeks after the election, the South Australian Liberal State Council – mulishly determined to show that it had learnt nothing from a result in which it was reduced to just two seats – passed a motion for the abandonment of the net zero target. It was orchestrated by backbench senator Alex Antic, who has led the takeover of the branch by hard-right fundamentalists.

Loading

(Antic is the protege of ex-senator Cory Bernardi. Remember him? He’s the guy who had to be sacked from a junior frontbench position after he gave a speech speculating that if Australia legalised gay marriage, the next step could be people having sex with dogs. Eight years on, Australia’s puppies remain happily unmolested.)

Net zero by 2050 is a distant aspiration, not a measure of present success. Its political importance is that it is a signifier of commitment to action on climate change. Despite the Morrison government’s adoption of the net zero policy, misgivings about the Liberal Party’s seriousness on the issue were an important reason why voters in the cities abandoned it in droves. Rescinding the policy would be understood by those people to mean only one thing: that the party was not serious about climate change.

The real metric of success is not what may (or may not) happen by 2050, but what will happen in 2030. Data on current emissions-reduction trends, including those revealed in the latest quarterly report published on May 31, suggest the government will fall well short of its 43 per cent target. That failure will have become obvious by the time of the next election.

The Liberal Party has a choice. It can frame the argument in 2028 as a debate about the failure of Labor’s policies. To do that effectively, it has to have credibility itself. Or it can spend the next three years having an abstract ideological argument about faraway 2050 targets, and make its internal divisions, rather than the government’s failure, the issue.

Loading

Yet there are those in the party room who want to do just that. They are usually people with no skin in the electoral game – commonly, senators in unlosable positions on Senate tickets. For these political onanists, the only elections that matter are internal ones.

When he became opposition leader, Whitlam knew that to win the confidence of middle Australia, he had to break the control Labor’s hard left exercised over key state branches. Nowhere was that more urgent than in Victoria where, as a result of more than a decade of Socialist Left dominance, Labor had not taken a single seat from the Liberal Party since the Split in the early 1950s.

His speech to the Victorian state conference in June that year was an epic denunciation of the mindlessness of ideological politics that drive a party to the political fringe: “We construct a philosophy of failure and find in defeat some kind of vindication of the purity of our principles. Certainly the impotent are pure.”

The Liberal Party’s hard right is the very mirror image of Labor’s hard Left. Both are equally as toxic to the electorate. Australians, in their wisdom, don’t like political extremes and won’t vote for parties that have been captured by them.

Ley is a very different style of opposition leader than was Whitlam. She will never achieve his oratorical greatness. But the political challenges she faces are essentially the same.

Whitlam won his internal battles and detoxified Labor’s brand. At the 1969 election, middle Australia rewarded him with a large swing that brought Labor close to government. Three years later, he seized the prize.

George Brandis is a former high commissioner to the UK, and a former Liberal senator and federal attorney-general. He is now a professor at the ANU’s National Security College.

Most Viewed in Politics

Loading