By David Ovalle

July 9, 2025 — 7.30pm

The Central Texas flash flooding that killed more than 100 people is among the deadliest flood events in the past 50 years. But it’s the disproportionate number of children who perished that sets it apart from others in recent history.

As of Wednesday (AEST), at least 28 children were among the dead, about a third of the total casualties, a number made more jarring in an era of modern forecasting and communication meant to prevent such disasters.

Twin sisters Hanna, left, and Rebecca Lawrence were killed by the flooding at Camp Mystic.Credit: AP/John Lawrence

Angry river water, engorged by historic levels of rain, attacked the most wholesome of American institutions: summer camps for kids. Unlike the “Children’s Blizzard” believed to have killed hundreds of young people in the Midwest in 1888, or the hurricane in Galveston, Texas, that collapsed an orphanage and claimed 90 kids in 1900, the scenes of innocence lost this time unfolded almost immediately on social media and television for a global audience.

The 10 girls from venerable Camp Mystic who remained missing amid the threat of more floods. The father desperately searching for his eight-year-old among twisted trees and waterlogged stuffed animals near the banks of the Guadalupe River. Twin sisters killed by flooding are granddaughters of a former Miami Herald publisher, who founded and chairs an organisation that advocates for early childhood education.

The Texas tragedy comes as experts worry that children around the globe are increasingly at risk from extreme weather events because they are smaller physically, less developed psychologically and dependent on adults for support and protection. An estimated 710 million young people around the world, most in developing countries, are at particular risk because of climate change, the advocacy group Save The Children estimated in 2021.

In the US, research on how natural disasters impact young people remains limited. Nearly two decades ago, US researchers analysed mortality data and concluded that among young victims, children between ages five and 14 are most likely to die as a result of cataclysmal storms and flood events – but such fatalities are few and far between.

“Overall, child death in disaster is very rare in the United States,” said Lori Peek, sociologist and director of the Natural Hazards Centre at the University of Colorado Boulder, who co-authored that study. “That is what makes a tragedy of this scale all the more disconcerting and makes it feel all the more urgent that we come together to prepare for future weather extremes.”

In Texas, the larger toll won’t be clear immediately. Child survivors – like those displaced by Hurricane Katrina in 2005 – will suffer psychological trauma long after the spotlight has receded. That could include separation anxiety, nightmares, depression, engaging in risky behaviours or withdrawing from activities, said Alice Fothergill, professor of sociology at the University of Vermont, who along with Peek studied the long-term effects of Katrina on kids.

“Disasters last a very long time in the lives of children,” Fothergill said. “They are incredibly vulnerable in so many ways.”

Military personnel carry a child’s camp trunk salvaged downriver from Camp Mystic along the Guadalupe River.Credit: AP

Taking stock of history

Tallying the number of children killed in natural disasters is difficult, particularly for events that happened decades ago when record-keeping was less precise.

Even declaring them natural disasters can be complicated. Scholars point out that the impacts of floods, fires, storms and earthquakes are exacerbated by human-produced vulnerabilities.

Earthquakes in Pakistan (2005) and Sichuan, China (2008) claimed thousands of young people who were crushed when their shoddily constructed schools collapsed. In 1988, more than 8000 children in Colombia are believed to have died when a volcanic eruption caused mudslides in a town built near the volcano, a tragedy marked by searing images of a 13-year-old girl who succumbed after she was trapped in the rubble for days.

How we define children is different too. The flood of 1899 in Johnstown, Pennsylvania – a hellacious storm caused a neglected dam to burst – killed more than 2200 people, most certainly an undercount. Officials recorded nearly 400 children among the dead.

Girls from a summer camp near the Guadalupe River are reunited with their families on Friday.Credit: AP

Working teenagers in the late 1800s, who today might be considered children, were often counted as adults, said Amy Regan, historian at Heritage Johnstown, a historic preservation organisation. In Johnstown, it could have been worse – most children were at home, not congregated at schools, when the dam burst. Still, 99 entire families died. “It was a matter of what the water picked up, what debris hit what area, what building you were in,” Regan said.

Nearly a century later, in 1977, another dam failure and flash flooding again devastated Johnstown, killing 84 people, including 19 children dead or missing.

More recent US natural disasters have inflicted high death tolls with fewer child deaths, but no less heartbreaking.

Estimates vary, but Hurricane Katrina in 2005 killed at least a dozen children in Louisiana alone, according to state death data. A tornado in Joplin, Missouri, killed 13 high school students in 2011. Two years later, a tornado in Moore, Oklahoma, collapsed a concrete wall at an elementary school, killing seven students.

Children arrive at a reunification centre in Ingram on Friday.Credit: NYT

Last week’s floods stand out because so many children were gathered in the Texas Hill Country, where about two dozen camps offer cooling refuge for students on summer vacation. For generations, young people have come to canoe, swim, fish, hike, practise archery – and taste freedom away from their households.

The region had experienced similar tragedy before: In 1987, 10 teenagers from a Christian camp died when their bus and van were swamped by a deluge of floodwater from the Guadalupe River and its tributaries.

The camper deaths underscore every parent’s worst fear: tragedy striking when you have entrusted your kids to the care of others, vulnerable and far from home.

“It’s similar to how we think about school shootings – schools are supposed to be particularly safe places,” said Jacob Remes, professor of disaster studies at New York University. “These deaths are not supposed to happen.”

Eight-year-olds Sarah Marsh (left) and Renee Smajstrla, who were both staying at Camp Mystic, died in the flood.Credit: Camp Mystic / Facebook

The Children’s Blizzard of 1888 happened when what had been a mild sunny day suddenly morphed into a maelstrom of wind and freezing weather across Minnesota, Nebraska, Iowa and the Dakotas. At least 200 people died – many students caught walking home from school. The Army Signal Corps failed to issue a cold warning the previous night, although at that time the telegraph was the speediest form of communication and newspaper accounts at the time revealed more outrage about damaged crops than dead children, said David Laskin, author of The Children’s Blizzard.

Nearly a century later, students and staff from Oregon Episcopal School found themselves in a similar freak snowstorm on Mount Hood, marring what was supposed to be an easy day hike to the summit. Nine people died in the 1986 tragedy, prompting an investigation, legal settlements and a wrongful-death lawsuit.

Loading

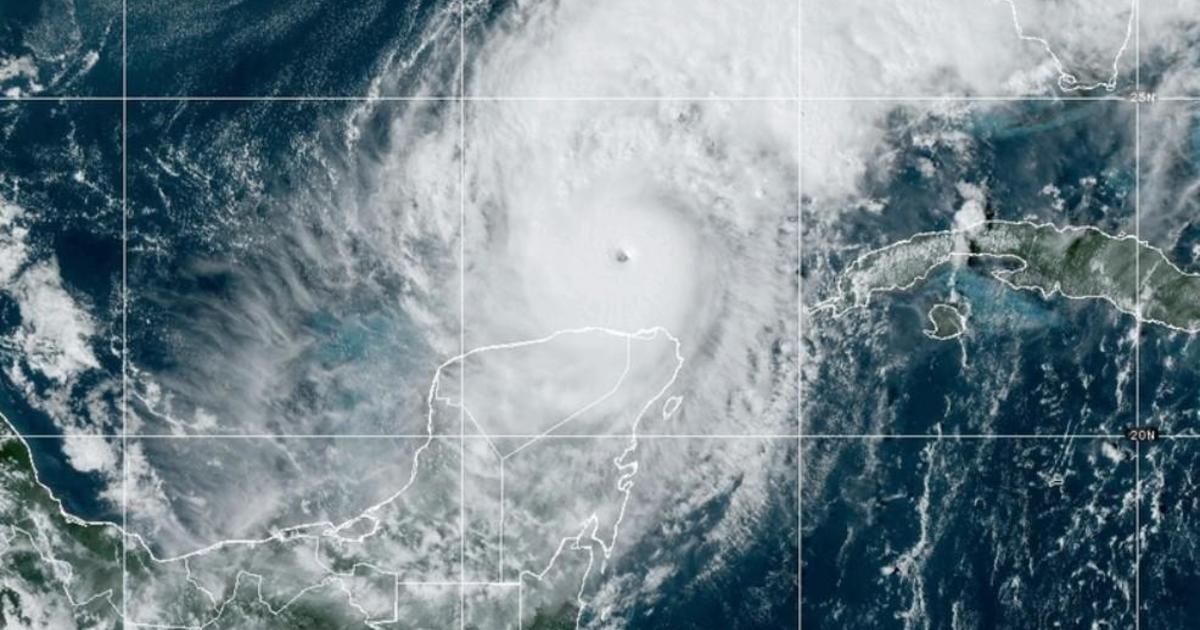

Now in 2025, with forecasters using state-of-the-art satellite technology and the ubiquity of smartphones, children aren’t supposed to die like they did in Central Texas. Officials vow to investigate whether warning systems were sufficient – or will ever be sufficient – in a region dubbed “flash flood alley” for its history of dangerous inundations.

“There is something particularly frightening about flash floods. They move so quickly. It’s so hard to predict where it’s going to happen,” said Remes, of NYU. “It’s coming in the middle of an incredible downpour – it feels very biblical.”

This article originally appeared in The Washington Post.

Get a note directly from our foreign correspondents on what’s making headlines around the world. Sign up for our weekly What in the World newsletter.

Most Viewed in World

Loading