Creative Australia’s one job is to invest in and champion Australian creativity. But its botched handling of the appointment of artist Khaled Sabsabi and curator Michael Dagostino to represent Australia at the 2026 Venice Biennale raises serious doubt about the organisation’s leadership and processes.

From books, music, paintings, plays and artists such as William Dobell and Barry Humphries, bureaucrats have thrown creativity to the wind to protect themselves. But rarely has an arts organisation been caught so cravenly looking over its shoulder for government approval, first dumping Sabsabi and Dagostino, and then when the coast was clear nearly five months later, reinstating them this week to represent Australia next year.

Their removal saw Creative Australia sacrifice integrity and judgment to a panic more political than moral that followed the Dural caravan bomb hoax, and graffiti and fire attacks around synagogues and schools. The agency’s artistic quandary was clearly fanned by Labor and the Coalition’s attempts to look tough on antisemitism in the lead-up to the federal election.

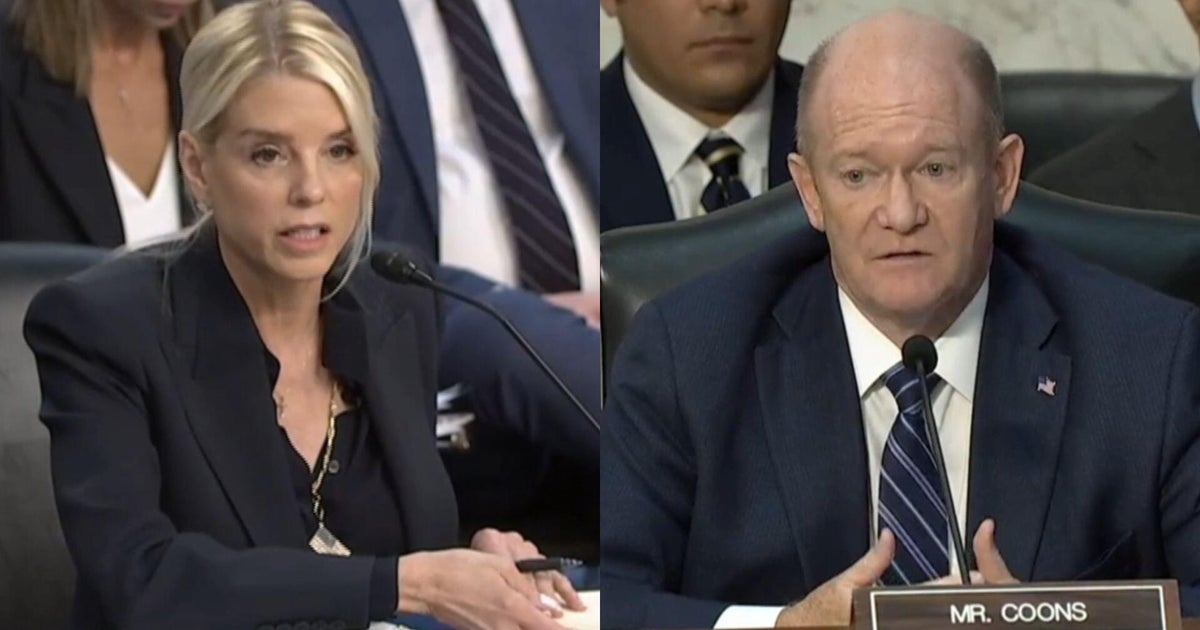

Artist Khaled Sabsabi (left) and curator Michael Dagostino.Credit: Steven Siewert

Creative Australia announced Sabsabi and Dagostino as our representatives to the Venice Biennale on February 7, after briefing Minister for the Arts Tony Burke. The previous month the caravan was found in Dural, and subsequently The Australian newspaper ran a story highlighting a 2007 Sabsabi video installation featuring Hassan Nasrallah, the leader of the Lebanese militant group Hezbollah, a declared terrorist organisation. The story prompted questions in parliament about two of Sabsabi’s historic works, and Burke then called Creative Australia’s CEO Adrian Collette, asking why he had not been alerted to the contentious artwork. Hours later, the board met and resolved to dump Sabsabi and Dagostino.

The board’s action triggered uproar in the arts sector, with artists pitted against the very organisation that is meant to serve them, resignations, and potential embarrassment on the international stage with admissions that the Australian Pavilion in Venice could be left vacant in the face of an artists’ boycott.

Loading

A subsequent review by Blackhall & Pearl into the pair’s abrupt termination on February 13 does not lay blame on any single individual for the “series of missteps, assumptions and missed opportunities”, but it has certainly reduced Creative Australia’s artistic credibility.

Its chair, Robert Morgan, retired last month and the Herald’s Linda Morris suggests Collette, an experienced arts administrator, will seek to set things right, and then make a diplomatic exit.

This is an organisation founded on the principle of artistic independence, but the episode illustrates the dangers of knee-jerk reaction and surrender to political pressure. Burke insisted he did not demand that heads roll, but it is clear some sort of collective political osmosis gripped Creative Australia.

With a base appropriation of $312 million in the 2025-26 budget, the agency had plenty of reasons to curry favour with political masters. But censorship is the job of law, not arts administrators, and despite the investigation, the public is little the wiser on how lobbyists, cultural warriors, an election and a distant conflict forced Creative Australia to self-harm.

Bevan Shields sends an exclusive newsletter to subscribers each week. Sign up to receive his Note from the Editor.