For most Australian children, school is a place to learn and to socialise. But for Khurshid Mohammadi, attending classes is an act of defiance.

When the Taliban returned to power in Afghanistan in August 2021, women’s rights were eroded, including access to education.

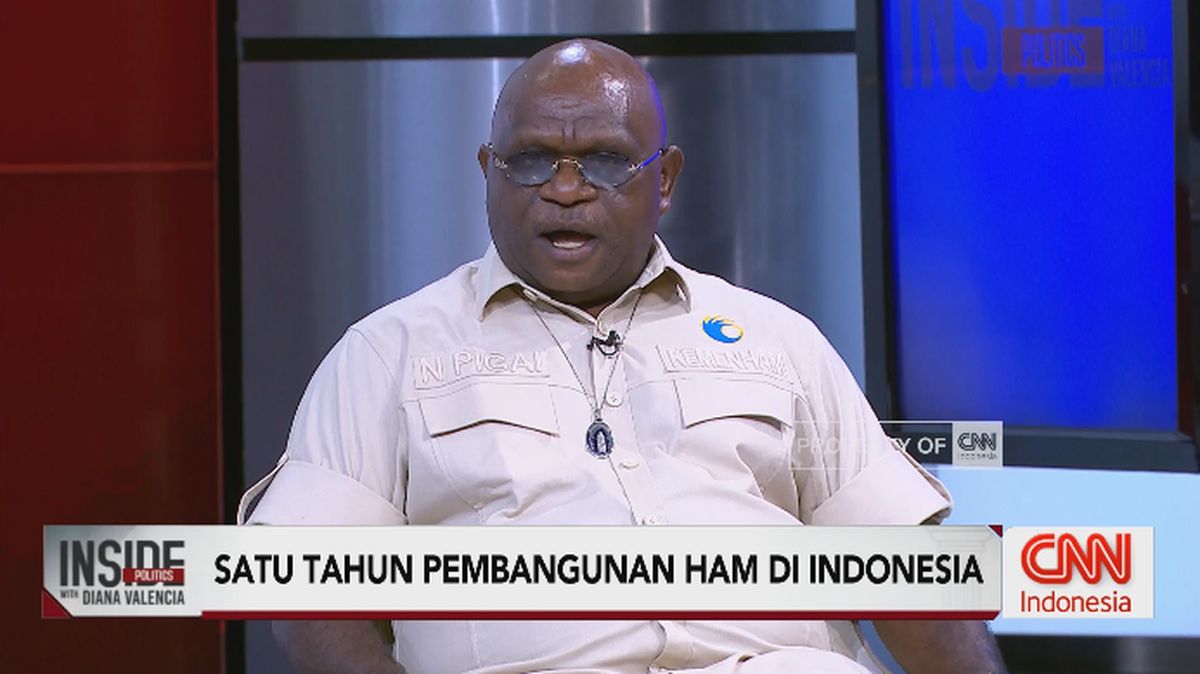

Boxer Khurshid Mohammadi is a student at North Melbourne’s River Nile School. Credit: Harjono Djoyobisono

“I was crying, it was unbelievable. Families were scared of the Taliban taking women from their houses,” said Mohammadi, 21. “It changed the dreams of women all over Afghanistan.”

But she, along with 120 other female refugees and asylum seekers, found hope and a community on the other side of the world at River Nile School, a small independent school in North Melbourne.

The unassuming school on Capel Street is a finalist for educational platform T4’s award for World’s Best School for overcoming adversity, alongside schools in Uganda, England, Latin America, Pakistan and war-torn Palestine.

Principal Charles Hertzog said the students – who he calls “friends” – had a real gratitude and desire for education that he hadn’t seen elsewhere.

Principal Charles Hertzog with students Raghad Jafari and Gulsum Saiahi at River Nile School.Credit: Justin McManus

“I think that having had education removed from you for some block of time, which is true for all of our young women, makes them their own advocates for school in really different ways, based on their lives and their family situations,” Hertzog said.

“But it does create this kind of shared camaraderie and gratitude that crosses over those country lines and experiences.”

He said access to education had been cut off for some students through civil conflict or patriarchal gender norms. Students had varying levels of education, English and trauma.

“We really want our friends to be finishing with us to the point that they can have financial agency and choice and decisions as they go on to the next step,” he said.

River Nile School opened in 2017 and teaches young women aged between 15 and 24 from around the world, including Afghanistan, the Horn of Africa and conflict-stricken Kayin State in Myanmar.

Students are offered free laptops, public transport fares, breakfast and lunch. The school also connects students with legal support, case management and trauma-informed practices, on-site VET subjects, and programs that allow students to complete VCE over a longer period of time.

“We have a really dedicated staff across a lot of really different disciplines that choose to work here, specifically because of our student cohort and our mission. And I think those two combining factors are the secret recipe of what we do.”

Raghad Jafari, from Iran, has been in Australia for 13 years. The recent Israel-Iran conflict has been a stressful time for her as she still has family there. “You never know, you just worry.”

She attended several mainstream schools in Australia but they were too overwhelming, busy or impersonal. She ended up not attending for months.

Raghad Jafari found her tribe at River Nile School.Credit: Justin McManus

“I went to three mainstream schools before this. You kind of get lost. When you have a smaller school like this one, it’s easier to have that connection and to say, ‘Hey, I need help’.”

When she finally found River Nile, she signed up on the day. It’s had a profound impact.

“Ever since coming here, I want to do educational support. The education team and support team here are really sweet. It made me realise I want to be like them. Because they helped me a lot.”

The connection with fellow students has also been helpful.

Gulsum Saiahi, who arrived in Australia from Afghanistan about a year ago to reunite with her father after 13 years, said her classmates are “like family, like sisters”.

“I’ve left my grandfathers, my aunties, my cousins. So that was a challenge. I really miss them,” she said.

“We have experienced how it is hard, education is a right for everyone. Education is the key to our success,” she said.

Hertzog said the school wants to help the women succeed on their own.

“It can be tempting to solve problems. And I think we’ve found over time that we need to be really careful, that the way that we’re removing barriers is doing that in a way that creates that skill and that agency for someone else to do it after we gone,” he said.

For Mohammadi, she wants to show the Taliban – and the world – that the regime won’t stop her. Last year, she was one of two women boxing on behalf of Afghan refugees in an international competition in Serbia. She dreams of competing in the Olympics.

“I’m going to this competition to show the Taliban that an Afghan woman, if they get a chance, they will do it best.”

Before she fled her home, Mohammadi was on the Afghan national women’s soccer team, which made her a key Taliban target. She escaped with the help of global players union FIFpro and the Australian government, after she and her teammates burnt their football jerseys and discreetly boarded a plane to freedom.

But her football dreams live on, with FIFA approving an Afghan women’s refugee team in May, which she hopes to play in.

Khurshid Mohammadi was a member of the Afghan women’s soccer team, who fled the country.Credit: Harjono Djoyobisono

“[The team] started again. They come back with power,” she said.

She plans to study social work at RMIT university to support other women with similar experiences.

Most Viewed in National

Loading