Simon Claringbold picked and ate some wild mushrooms from his garden. Days later, he thought he was taking his last breaths.

Erin Patterson has been found guilty of murdering three people and trying to kill a fourth by poisoning them with death cap mushrooms.

See all 25 stories.The mushrooms, growing in the gentle shade of a backyard oak tree, had big, flat heads and thick stems. They looked too good not to eat.

“I thought, ‘They would go really great on my spag bol for dinner,’” Simon Claringbold recalled. “They just looked like field mushrooms.”

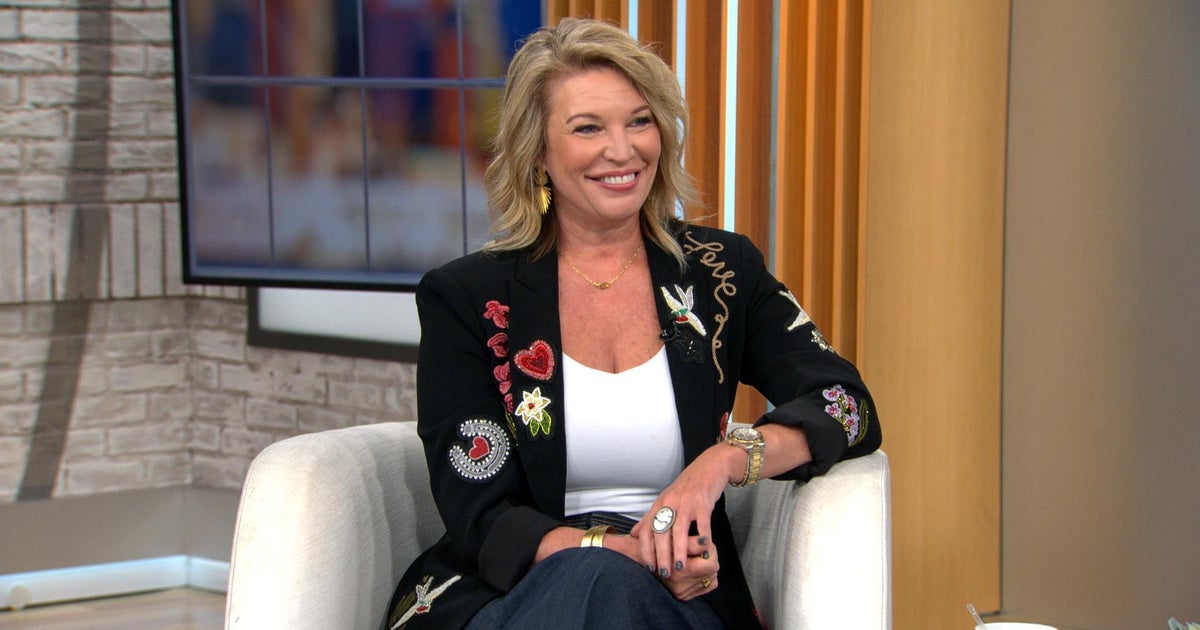

Simon Claringbold is one of Australia’s few survivors of death cap mushroom poisoning.Credit: Alex Ellinghausen

Within days, Claringbold was near death in a hospital bed.

“The lights were going out. I thought this was the end,” he said.

Loading

The mushrooms Claringbold ate more than 25 years ago were not Agaricus campestris – field mushrooms – but Amanita phalloides – death cap mushrooms.

He is one of Australia’s few survivors of death cap mushroom poisoning.

Another survivor is Ian Wilkinson, who was deliberately poisoned at a lunch held by relative Erin Patterson. Patterson was this week found guilty of attempting to murder Wilkinson, and murdering his wife, Heather, and her in-laws, Gail and Don Patterson, with a beef Wellington meal laced with death caps.

Death caps contain amatoxin, a chemical of startling lethality. After exposure, without treatment, “basically, every single cell would die. It would just kill it,” said University of Sydney geneticist Professor Greg Neely, who has studied the toxin. There are no proven successful treatments. For doctors, it is a mix of luck and hope.

An introduced species from Europe, death caps are becoming increasingly common in Australia as new subdivisions are planted with the oak trees that can harbour the fungi.

Recently, Claringbold saw a cluster of death caps growing near his neighbour’s letterbox and kicked them over.

Death cap mushrooms.Credit: iStock

“In Europe and the US, there probably is an awareness because people know they are in the environment,” he said of the deadly species. “In Australia, we think we’re different, we don’t have it. But we do.”

‘They tasted like tripe’

Claringbold grew up in the country, surrounded by sheep paddocks fringed with eucalyptus trees. As a child, he regularly foraged under the shade of the gums for field mushrooms, taking punnets of fat fungi home to grill on the barbecue.

After a long afternoon gardening at his Canberra home in 1998, when he came across some wild mushrooms, his eyes lit up.

His wife and children were more sceptical, put off by the slight greenish tinge. Not Claringbold. He ate three of the mushrooms, cooked and sliced over that night’s dinner.

They tasted like tripe, he said, but not bad enough to make him wary.

Claringbold, who works in IT, cites the Dunning-Kruger cognitive bias to explain why he picked and ate the wild mushrooms: the less we know about a topic, the more confident we tend to be in our knowledge. He was confident enough in his knowledge of mushrooms to eat some that nearly killed him.

Death caps are symbionts, meaning they live in symbiosis with other organisms.

They live in the roots of introduced trees – typically oaks, like the one overhanging Claringbold’s backyard – and trade nutrients with the tree in a mutually beneficial relationship.

Professor Brett Summerell, chief scientist at the Royal Botanic Gardens in Sydney, said: “Probably in the last 10 or 15 years we’ve started to see it be more widely spread, because there’s a preponderance of people growing oak trees in the right places for it to fruit.”

Nearly all the mass of the fungus sits below ground; it breaches the surface when it comes time to reproduce. The cap shades a stalk (known as a stipe); gills fan out beneath the cap, from where the fungus spreads spores through the air.

It is these areas where the concentration of the mushroom’s deadly poison, amatoxin, is highest.

Amatoxin, the death cap’s deadly poison

Amatoxin is an unusual molecule. Most proteins look like long strings folded together, but amatoxin belongs to a class known as cyclic peptides, in which the ends are joined in a loop.

From left: Don Patterson, Gail Patterson and Heather Wilkinson died after ingesting poisonous mushrooms. Ian Wilkinson is the sole-surviving lunch guest.

Micro-organisms and drug developers have gravitated to cyclic peptides because their shape gives them an exceptional level of stability: they are not destroyed by heat or stomach acid. A death cap mushroom can be charred black and its toxins are no less lethal.

Loading

Claringbold went to bed after the meal and felt no ill effects. He cycled to work the next morning, still feeling fine. It was only about 3pm that he started to feel unwell – but not so bad he was unable to ride home.

“I was having bad diarrhoea. My wife was going ‘oh, I reckon it’s those dodgy mushrooms from yesterday.’”

A typical patient will experience nausea, vomiting and stomach cramps about six hours after first eating death caps – which is unusual, given other poisonous mushrooms tend to quickly induce symptoms.

But the amatoxin soon left Claringbold’s stomach and headed towards his liver, a biological filter between the food that is consumed and the bloodstream. Amatoxin binds strongly to an enzyme called RNA polymerase II, gumming it up.

Loading

RNA polymerase II is used by nearly all life as an essential step in translating our genetic code. The poison essentially turns off the body’s ability to read its own DNA.

“If you’re trying to mess with other animals … you want to pick something super-common to all life, basically,” said geneticist Neely. “That’s basically the enzyme that allows us to express our genome.”

Cells contain lots of self-regulation mechanisms to sense when something goes seriously wrong. Being unable to read a body’s DNA is one of those moments. The cell triggers a self-destruct sequence.

“It just goes, ‘OK, I need to check out,’” Neely said.

‘I thought this was the end’

Claringbold recalls no pain or even vomiting – just waves of nausea. A friend of his, a doctor, came around to check on him. He took one look at the suspect mushrooms and rushed Claringbold to hospital.

Claringbold was soon taken via air ambulance to Royal Prince Alfred Hospital in Sydney, where doctors put him on an intravenous infusion of penicillin – one of several treatments doctors try for amatoxin.

“Often, when there’s so many treatments, what it really means is we don’t have one that’s really good,” said Dr Jonty Karro, a toxicologist and director of emergency medicine at St Vincent’s hospital.

In theory, the antibiotic can cut uptake of the poison by the liver, but no one is really sure how well it works.

Loading

As the liver cells die, the organ loses its ability to filter blood. Toxins build up and circulate through the brain, which can cause swelling and damage. The kidneys, which perform a secondary filtering function behind the liver, also take up the amatoxin and start dying.

In hospital, Claringbold was starting to drift in and out of consciousness. He recalls his vision narrowing, as though he were in a dark tunnel, but he still was not in pain. “It was definitely life or death. The lights were going out. I thought this was the end.”

In his moments of lucidity, he remembers watching a chart – probably a measure of damage done to his liver, doctors say – tracking up and up at a constant angle.

“It was like: I’m going to be dead in two days,” he said.

Loading

And then the rise seemed to slow, and plateau, and then fall. Claringbold thought he might not die immediately. And then he thought he might not die at all. About 11 days after he entered hospital, Claringbold was released. It took him another month to recover. Amazingly, he has no long-term damage, the liver being the only internal organ that can regrow.

Typically, 25 to 50 per cent of people poisoned by death caps die.

Claringbold isn’t sure why he survived; perhaps because he was young, fit and healthy. Or just lucky. One mushroom is usually enough to kill, and Claringbold ate about three.

“There were a ton of lessons for me, just being really laissez-faire with risk,” he said. “You have to be careful.”

Most Viewed in National

Loading