By John Shand and Peter McCallum

July 20, 2025 — 1.33pm

OPERA

Rusalka. Opera Australia

Sydney Opera House. July 19

Reviewed PETER McCALLUM

★★★★½

Making a welcome and triumphant return to Sydney, Nicole Car sang the title role of Rusalka with all the warmth, strength and depth of humanity that notionally eludes the operatic character she portrays.

I say “notionally” because Rusalka is an allegory for a person who, in failing to understand human fickleness, superficiality and venality, ends by performing the most deeply human act of compassion, sacrifice and love.

Nicole Car as Rusalka.Credit: Carlita Sari

Car is at her magnificent best when opening out climactically at the peak of phrases with thrilling sound and immaculate melodic arc, but the sound is evenly controlled and shaded across the full range. She unfolded the lines of the opera’s most well-known aria, Song to the Moon, with gentle reserve, allowing the melody’s natural grace to place a stamp of beauty on this mysterious tale at its outset.

It is a performance that fulfils in every respect the exciting promise Car revealed in her earliest roles with Opera Australia (including as Michaela in Carmen, one of the first roles in which she attracted listeners’ ears).

Tenor Gerard Schneider sang her Prince with attractive light sound and Disneyesque good looks, true in pitch and tone and unforced in expression. As the Water King, Warwick Fyfe maintains a fierce, fretful and doom-laden tone, his chief narrative function being to warn that this isn’t going to end well.

His appearance in this role accentuated the resonance of Dvorak’s opening scene with that of Wagner’s Rheingold, in which Fyfe sang a ferocious Alberich in 2023. As though to clinch the connection, director Sarah Giles has chosen to locate this scene not beside the lake, as the stage directions say, but in it.

Charles Davis’s set, David Bergman’s projections and Paul Jackson’s lighting create this illusion deftly, conjuring a sense of strangeness and, later, of alienation from the brightly lit vacuousness of the human world. Poetically, the water is the cool subconscious, linked with the unsullied but austere purity of moonlight, which, though corrupted by human contact, remains an ideal of chaste beauty that the Prince aspires to but can attain only in death.

By contrast, the human scenes in the castle are filled with paper-cutout people. In this world, Natalie Aroyan has a glowering edge to her tone as Rusalka’s flouncing rival, the Duchess. Just as Dvorak leavens the gloom with folk-like music (anticipating the stylistic collisions that his compatriot Janacek was later to exploit), Giles mixes the opera’s sorrowful aspect with comedy.

Andrew Moran and Sian Sharp inject rustic simplicity and humour, Sharp singing with incisive brightness. A different level of comic subversion comes from Ashlyn Tymms as the witch Jezibaba. With shopping trolley and glittering accessories, she pollutes both the human and natural world to feed acquisitive consumption, and Tymms sings her mocking incantations with penetrating brittleness.

Renee Mulder’s costumes range from pallid fish-like grey for the water dwellers to meretricious colour for Jezibaba. Her Wood Sprites, brightly sung by Fiona Jopson, Jennifer Bonner and Helen Sherman, lumber comically with branches for arms and bad hair.

Conductor Johannes Fritzsch mines the symphonic richness of the orchestral textures expressively though he, and the Opera Australia Chorus articulated crisply the distinctly Czech snaps in the rhythm. At the end, Giles has Rusalka ambiguously turn towards Jezibaba, undermining Dvorak’s redemptive message with a hint that malignancy is constantly shape-shifting.

THEATRE

CIRCLE MIRROR TRANSFORMATION

Wharf 1 Theatre, July 17

Until September 7

Reviewed by JOHN SHAND

★★★½

Annie Baker can make a play out of minimal words and minuscule gestures. The effect borders on shock because we’re so used to huge emotions with titanic consequences. You have to readjust, put your antennae on higher alert.

Baker wrote two of this century’s best plays: The Aliens and, above all, The Flick, about the death throes of a cinema. If Circle Mirror Transformation isn’t in that league, it’s because her sheer daring doesn’t always succeed.

On the page, the play sometimes presents the merest sketches of the characters, and at other times, she exercises infinite precision about what happens and, most particularly, what doesn’t happen. If the spaces between notes define a rhythm, the spaces between words or events can define the feel as well as the pace of a play.

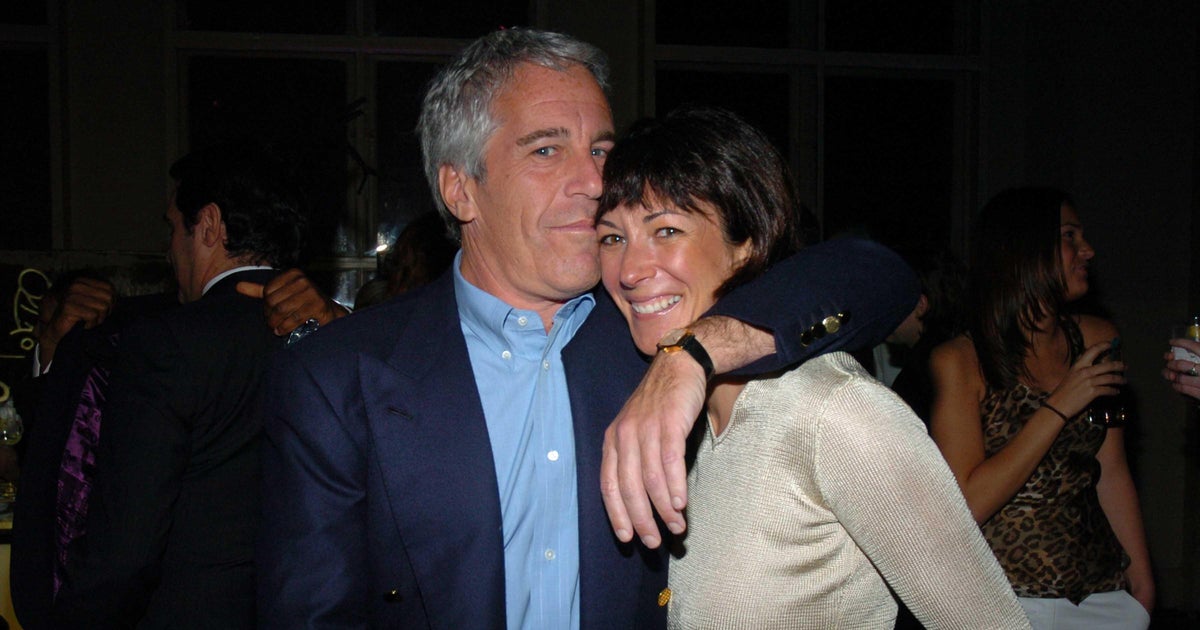

Cameron Daddo and Ahunim Abebe. Credit: Daniel Boud

Just as Beckett famously used a metronome when directing a Happy Days production, so one can imagine Baker writing Circle Mirror Transformation with a stopwatch by her side.

The setting is a weekly adult acting class in a Vermont community centre, run by Marty, admirably played by Rebecca Gibney after a 20-year hiatus from the stage. Marty doesn’t use texts, but rather games and improvisations. Her four students are James, her husband (Cameron Daddo), Schultz, a recently divorced carpenter (Nicholas Brown), Theresa, an ex-actor (Jessie Lawrence), and high school student and wannabe actor Lauren (Ahunim Abebe).

We come to know them by the way they engage – or don’t – with Marty’s games, and by how they interact before, during and after these sessions. Baker manages to squeeze fulfilled and unfulfilled romances into her scenario, but they are merely cross-hatched; we do the colouring-in.

Poor Lauren was hoping to do some “real” acting before auditioning for a West Side Story production, and she speaks for us when she doesn’t “get” some of the perverse and even irritating games. It’s in the repetition of these that Baker dares us to stay on board, the experience being akin to one of those elaborate jokes where you pray the pay-off is worth the wait.

For me, she stretched our patience. In this Sydney Theatre Company production directed by Dean Bryant, the casting and acting are largely on point, with Gibney and Daddo bringing an easy charisma to bear that suits their likeable characters.

Schultz and Lauren suck us in, too, with Abebe’s portrayal of the latter replete with her toes pinching each other as she initially feels excruciating discomfort in participating (just as Gibney beautifully “conducts” her exercises with tiny hand gestures). Theresa is the least interesting character, and Lawrence does well to keep us engaged.

If you want to see a play contrived almost out of thin air; a play with warmth, humour and a perfect capturing of our stuttering attempts at real communication, this is it, yet you leave with a nagging sense that a deeper emotional impact went begging.

Most Viewed in Culture

Loading