Prisons are often considered hidden, closed-off places – areas defined by how removed they are from everyday life. Most will go their entire lives not seeing the inside of one, perhaps fearing them or the people inside.

This is not the case for Tyson Tuala, a former prison guard stationed at the soon-to-be closed Port Phillip Prison. After working at the maximum-security jail for nearly four years, Tuala learnt every facet of the prison experience, including the “yellow line”, a metaphorical and literal boundary between guards and inmates. This divide was rarely crossed; however, Tuala became one of the few who managed to.

Tyson Tuala knows the prison system better than most. Now, he’s bringing it to the stage.Credit: Chris Hopkins

Now president of Melbourne-based Māori association Ngā Mātai Pūrua Inc., Tuala knew he wanted to share his story, along with those of the inmates he guarded, to lift the curtain on the prison system. But it wasn’t until he met Alaine Beek, founder of Essence Theatre Productions, that he discovered the best way to do so.

Together, they created The Yellow Line, a stage play based on Tuala’s real-life experience of attempting to teach a group of disinterested inmates the haka.

“If people can see and hear these stories, it starts to break down those barriers or the assumptions of what it’s like for different people – for guards, for prisoners,” Tuala says.

“If you only ever hear stories like your own, your beliefs will never be challenged … seeing this with 200 to 500 other people, it helps you change your mind, it creates empathy, it helps you release anger and frustration.”

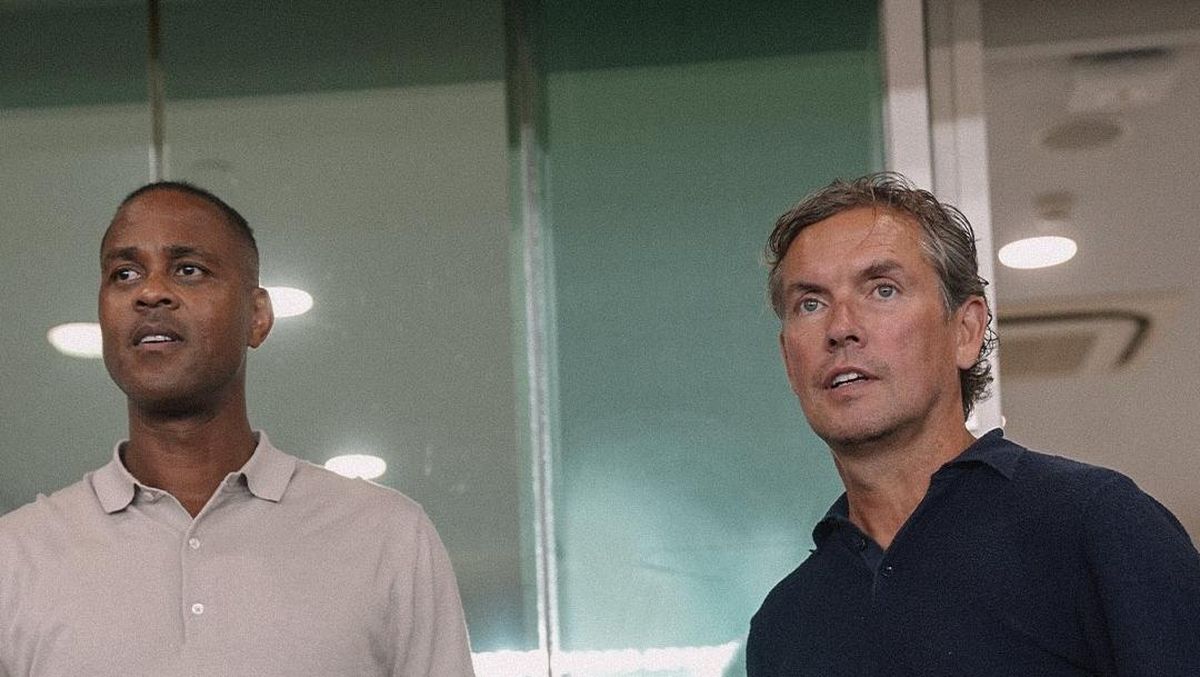

Tyson Tuala (left) and Alaine Beek (centre) alongside actor Wiremu Morris (right), who stars in The Yellow Line.Credit: Chris Hopkins

The Yellow Line doesn’t just reveal what it’s like inside a prison, it also shines a light on Māori and Pacifika communities, which are disproportionately impacted by incarceration in Australia. This, Tuala says, will hopefully resonate with First Nations people, who are also overrepresented in the Australian criminal justice system, and who helped pave the way for him to share his story on Woiwurrung Country now.

Many Australians’ only existing encounter with the haka – a Māori ceremonial war dance – may be while watching the All Blacks before a rugby game. However, Tuala says the play explores its deeper cultural and emotional significance.

“Haka is one of the best ways to express feeling, and also one of the best ways to tell a story. That’s why it’s so powerful in a prison context because it’s a really safe way of expressing extreme frustration, anger, sadness, grief, happiness, celebration.”

It’s these kinds of raw and distinctly human feelings that The Yellow Line explores. Made up of a nine-person cast, in which only three are trained actors, each character is based on a real person from the Australian prison system, bringing the audience inside prison walls.

Before co-writing the screenplay, Beek and Māori community leader Berne-Lee Edwards, visited the Metropolitan Remand Centre to witness a Waitangi Day performance (commemorating the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840) and to interview several prison guards and prisoners.

“That offered such insight into the heart of the story,” Beek says. “It’s often the little things that you see – like how nervous some of the prisoners were when they had to talk to us – that you end up using … I was just drinking everything in, the imagery, the vibe, the energy. I understood the world a bit more.”

It’s probably the most impactful play she has written, Beek says, largely because of how rooted it is in truth and reality.

Though no actual prisoners performed in the play (Beek says they tried to secure someone, but were unsuccessful due to timing issues), those who inspired the characters were honoured to be represented on stage – after they believed it was actually happening.

Alaine Beek co-wrote The Yellow Line with Berne-Lee Edwards to show audiences the humanity within prisons.Credit: Chris Hopkins

“I don’t think they believed me at first,” Tuala says. “I usually do different small things with community groups, but I don’t think they realised this would be in front of thousands of people.”

The first season of The Yellow Line in May saw multiple standing ovations. A prison guard, who currently teaches haka in prisons, even performed a solo haka as a form of thanks at the end of one show. After its closing night, the entire audience stood and performed the haka to the actors on stage.

“Someone from the audience told me it’s more than theatre … You just feel it,” Beek says. “As humans, we connect to truth. It’s a human story of feeling isolated and trying to find a sense of belonging, trying to find purpose.

“It’s now just a question of where do we go next? I’m already thinking about touring.”

Loading

The Yellow Line is presented by Essence Theatre Productions and Ngā Mātai Pūrua Inc. It will be performed at the Wyndham Cultural Centre three times between July 26 and 27.

The Booklist is a weekly newsletter for book lovers from Jason Steger. Get it delivered every Friday.

Most Viewed in Culture

Loading