By JP O'Malley

July 2, 2025 — 12.00pm

COLD WAR

The CIA Book Club: The Best-Kept Secret of the Cold War

Charlie English

HarperCollins, $29.99

In Nazi Germany books considered to be un-German were burnt in public. No such public ritual existed in the Soviet Union, where censorship was secretive and subtle.

During the Cold War (1945-1989), the Polish government suppressed culture behind closed doors too. The most populous central European country was then aligned to Moscow, which meant any criticism of the Kremlin was off limits.

This Sovietisation of Polish culture was resisted by certain writers, such as Czesław Miłosz, who fled to Paris in the early 1950s. The Polish poet won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1980, but his writing was banned in his native country. As was the work of many western writers, including George Orwell, Hannah Arendt, Albert Camus and Virginia Woolf.

But in communist Poland an underground literary culture still flourished. Books came from the west via various channels and sources. Some were hidden in the toilets of sleeper trains shuttling across Europe. A copy of The Gulag Archipelago, by Russian dissident Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, was said to have been concealed in a baby’s nappy on a flight to Warsaw. But banned literature wasn’t coming into Poland by sheer chance. “[It was] part of a decades-long US intelligence operation [that built] up libraries of illicit books on the far side of the Iron Curtain,” Charlie English explains in The CIA Book Club.

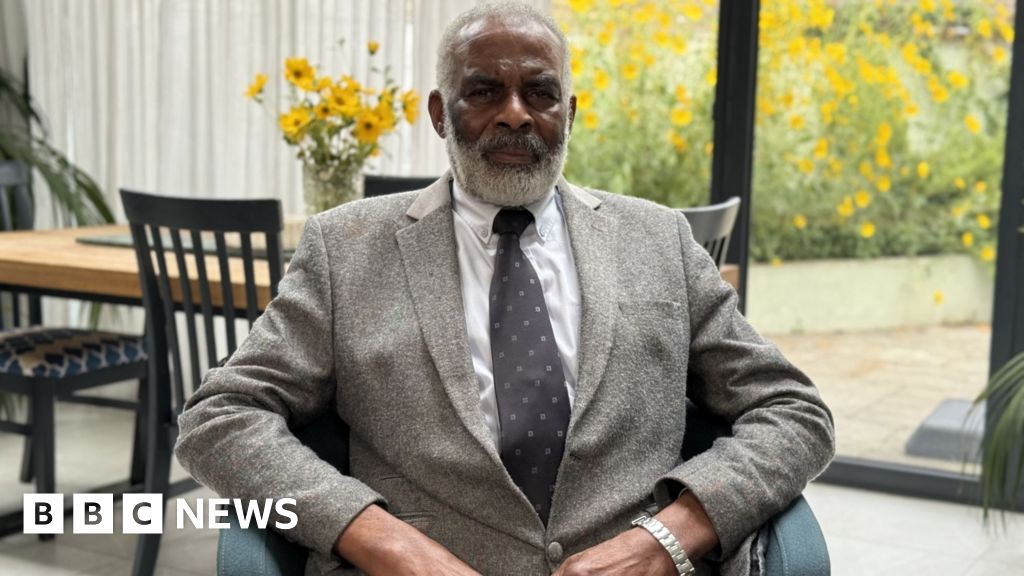

Journalist and author Charlie English.Credit: Nicola Hippisley

The British author begins this captivating story in 1955, when Free Europe Press printed 260,000 copies of Orwell’s 1945 political fable Animal Farm, which were sent by balloon into East-Central Europe. But the clandestine mission, the brainchild of Free Europe Committee (FEC), an anti-communist CIA front organisation, wasn’t very successful. So Langley, CIA headquarters, came up with a more effective strategy: direct mail.

Post was strictly censored behind the Iron Curtain, but some books got through. “No country responded with greater enthusiasm than Poland,” writes English, a former Guardian journalist. A persistent researcher who writes with flair, he notes that books with more controversial themes were typically sent to privileged intellectuals less likely to be persecuted. Among that list was Cardinal Karol Wojtyla, the Archbishop of Krakow, later elected Pope John Paul II. The world’s first Slavic Pope had been receiving books— indirectly at least— from the CIA for years. But like most of the recipients, he had no clue where the books were coming from.

The CIA book programme was “a complex organisation ... consisting of bookshops, publishers, libraries, book exporters, and Russian and East European personalities” living in various European cities, as George Minden once put it. During the mid-1950s the Romanian exile began working for the Free Europe Press Book Centre in New York, which handled the CIA’s mailing project.

Two decades later, Minden was president of the International Literary Centre (ILC), which controlled CIA literary influencing programmes across the Eastern Bloc and in the Soviet Union. Minden’s final field report in late January 1991 noted that the ILC had sent close to 10 million cultural items east of the Iron Curtain over a period of around 35 years.

Most files linked to the CIA programme remain classified, but Minden’s notes, made over several decades, are not, and English makes great use of them to piece together a compelling narrative that feels closer to a Cold War spy thriller than political history.

Elsewhere, English quotes from dozens of interviews with a colourful cohort of intellectuals, journalists, editors and dissidents, all of whom were directly affected by the programme, including Adam Michnik. The Polish writer had been a leading adviser to Poland’s Solidarity trade union, one of the most influential workers’ movements in postwar Europe. After martial law was introduced in Poland in 1981, Michnik became one of Poland’s most famous political prisoners and was eventually freed in August 1986.

English makes a convincing argument that Poland’s arduous path to intellectual freedom, and to democracy, are inextricably linked. Michnik was front and centre of that struggle. In May 1989, he co-founded Poland’s first independent daily newspaper, Election Gazette.

Loading

That November, the Berlin Wall fell. But it’s worth remembering that it was Poland— not Germany— that was the first domino to fall inside the Eastern Bloc. A monumental turning point came on June 5, 1989, when the Solidarity movement achieved a major victory in Poland, in what turned out to be the most significant election there since before the Second World War.

The final word goes to Michnik, who subtly suggests that literature played a significant role in ending the Cold War. “A book is like a reservoir of freedom, of independent thought, a reservoir of human dignity,” Michnik says. “We should build a monument to books.”

The CIA were no doubt very pleased. But they kept schtum.

The Booklist is a weekly newsletter for book lovers from Jason Steger. Get it delivered every Friday.

Most Viewed in Culture

Loading