Glenn Sanders was a troubled genius, and when it came to heavy machinery there was just about nothing he couldn’t fix. But by the time he went off the rails, his mind had turned to destruction, not construction.

Sanders mixed a deadly cocktail – an appetite for smoking meth that brought on acute paranoia, and an explosives licence that allowed him to stockpile a military quantity of homemade bombs.

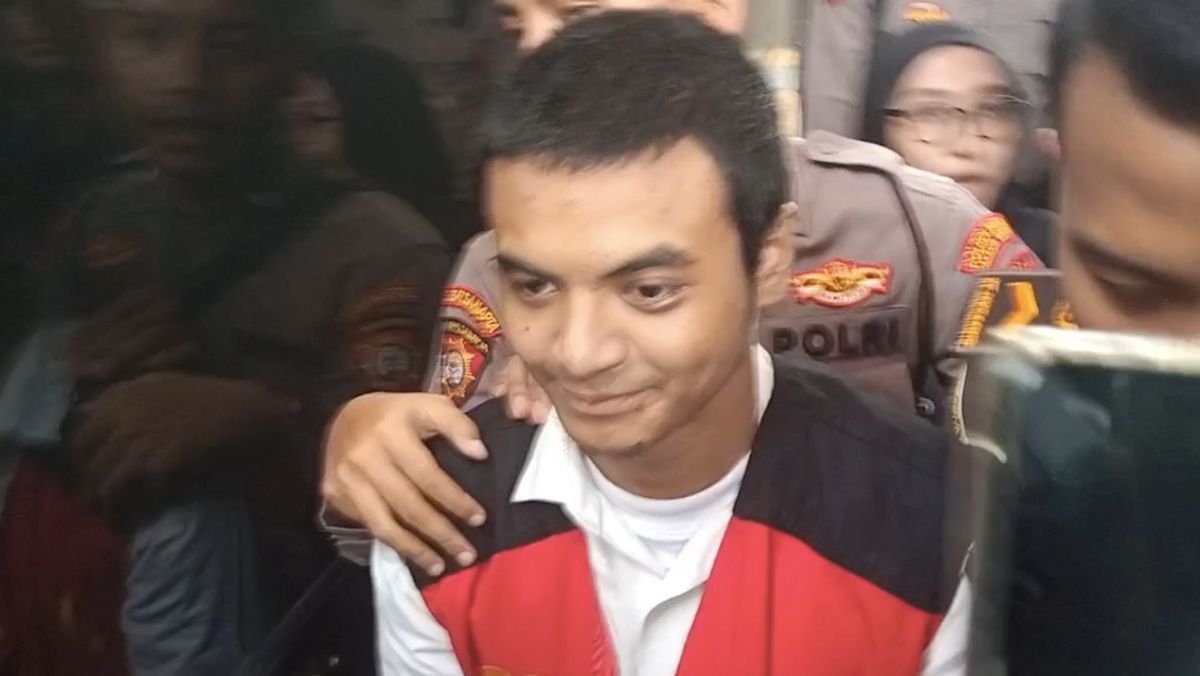

Deadly cocktail: Glenn Sanders at his property in Derrinallum in 2014.Credit: Leigh Henningham

But the self-taught expert made a rookie mistake. He failed to tell the time. When he had an inevitable stand-off with the special operations group, many of his explosives had been laid in seven interconnected bombs linked to a clock detonator.

Trouble was the trigger was set on daylight savings time, which had ended a week earlier.

For the first time, the inside story of Sanders, and many other secret police operations, has been told by veteran SOG member John Taylor in the book Through Fear and Fire: The explosive true story of a bomb squad veteran.

Usually, an author includes a CV on the back cover. For the sake of brevity, let me produce Taylor’s edited package. He is one of the longest-serving and smallest (in stature) SOG members, and its longest-serving bomb disposal expert. He has been shot at three times, fired shots at armed offenders, and been in three major collisions (once driving into an armed robber trying to escape with a million dollars). He has run nearly 20 kilometres with a broken ankle, disabled countless bombs that could have blown him to Iran, set charges to blow open fortified targets, suffered frostbite, and required two knee replacements.

Oh, and he climbed Mount Everest.

Taylor served at the SOG for 33 years. He was known as JT, although for a while he was called “Kelvin” for attempting to shoot an armed offender through a fridge (the shot stopped in the meat-filled freezer). “The fridge was a Kelvinator,” he explains.

We will return to JT, but first to Sanders and the stand-off at Derrinallum, which sits under Mount Elephant on the Hamilton Highway.

Locals became used to the sound of explosions from his property, and it was rumoured he wore an explosives vest when he left the house.

“The military-grade cannon he’d made was capable of firing large projectiles, and it was confirmed that he’d fired cannonballs at Mount Elephant, even landing a few on top,” Taylor writes. The 380-metre peak was 1500 metres from Sanders’ property.

A rocket is almost unscathed after explosions destroyed Glenn Sanders’ farm.Credit: Darren Apps

Taylor says that when Sanders’ explosives licence was about to be taken from him, he “started amassing sticks of Powergel, gelignite, charges, detonators, reams of detonator cord and other bits and pieces”.

After the loss of his second wife to cancer, Sanders used ice to keep him awake so he would not be ambushed by imagined enemies. He buried booby traps, built secret underground containers, and littered his property with sensors to alert him if anyone approached.

When authorities went to the property to seize explosives, they didn’t find his three underground storage units.

Social workers, medics and police would check on “Colonel Sanders”, but the general view was that if he was left alone, he would remain harmless.

That is until April 11, 2014, when Glenn woke and had his usual breakfast of a chocolate milk and an ice pipe. Then he left to visit his ill mother at the local hospital wearing his suicide vest. Now the police had to act.

The siege at the property lasted seven hours, with Sanders repeatedly telling police he didn’t want to hurt them. There was no way the SOG could rush him because the vest had three detonating points, including on the shoulders, so that even if he was handcuffed, he could use his chin to detonate.

“A few times he asked the negotiators the time,” says Taylor.

Just after 4am on April 12, there was a massive explosion (felt 30 kilometres away) from the seven bombs. He had rigged them so professionally that while most of the area was obliterated, his mother’s house on the property remained intact.

Then Sanders was gone. His vest detonated, and his remains were found scattered around the property. Three SOG members were hurt in the blast.

Taylor believes it was an accident, and Sanders expected the big bomb to detonate later.

“It went off an hour before he was expecting,” Taylor says.

“One SOG member who was watching said he looked shocked and involuntarily shrugged his shoulders. That set it off.”

In the SOG there are many types of bravery which require different characteristics. During a raid, it is adrenaline-filled, in a siege it is patience, and for the bomb response unit, it is working at your best when knowing one mistake might be your last.

Taylor knew the police-issue suit didn’t make him Superman. As a reminder, he had been shown a picture of an Indonesian bomb technician who was wearing a similar suit when he made a mistake. He was “spread all over the scene – his suit torn to shreds”.

For three weeks after the blasts, Taylor and two colleagues spent 12 hours a day in their suits searching the property, setting off 22 counter-charges, destroying booby traps. “Every piece of equipment and item of clothing on the premises was checked, and we found explosives in the pockets of various pieces of clothing,” Taylor recalls.

Because of the risk, the Hamilton Highway was closed for three weeks.

When Taylor’s team blew a hole in a trapdoor, they found $200,000 in cash that Sanders had withdrawn from a bank weeks earlier.

It was not the only time Taylor found a fortune during a life-and-death operation.

John Taylor arrests Stephen Asling, who is having a very bad day.

On July 28, 1992, he was one of 52 police at Melbourne Airport waiting to arrest three armed robbers.

For four months, police had been working on bandits Normie Lee, Stephen Asling and Stephen Barci, who were planning a massive stick-up.

The gang had already carried out two jobs, netting about $430,000, and had fired a shot during an armoured van hijack.

This time they had two targets: the Tip Top Bakery payroll or the Ansett depot at Melbourne Airport. They chose the airport, looking to grab at least $1 million in cash that was to be flown to Mildura banks.

What they didn’t know was that police were listening to their calls, which usually ended with the gang singing the 1930s show tune We’re in the Money.

The bandits had a .38 revolver, a .357 magnum, a .380 pistol, a .223 rigged as a machine gun with 26 cartridges, and a .308 rifle. They also had three rubber masks (two Michael Jacksons and a Madonna) for disguises.

The special operations group vehicle (right) smashes into the bandits’ panel van at Melbourne Airport in July 1992.Credit: Police surveillance

The SOG arrest van was parked about 100 metres away in Depot Drive, and John Taylor was the driver in the intercept vehicle.

Asling reversed the stolen van to the Ansett office, allowing Barci and Lee to jump out of the back of the van and grab three large bags containing $1,020,000.

The pair threw the money into the van and were inside about to bolt the rear door when Asling saw the police, immediately flooring the accelerator, which threw his pals and a sack of cash from the van.

The SOG plan to drive into the getaway van from behind was in tatters, and just as well. A machine gun was mounted in the rear of the van, so the bandits could swing open the door and mow down pursuing police.

On foot and surrounded, Barci and Lee pointed guns at police. Lee was shot dead and Barci severely wounded.

John Taylor about to reach the peak of Mount Everest.

Meanwhile, Asling had reached 80 km/h, heading for the airport exit. If he made it, there would be a dangerous high-speed chase. Taylor made sure he didn’t.

“The speedometer had just reached 90 km/h when I turned the steering wheel sharply to the right and bounced the car over the concrete median strip.

“Asling attempted to swerve to avoid us, but it was too late. A split-second prior to impact, I removed my hands from the steering wheel to prevent injury and clenched my teeth, so I wouldn’t break any. The impact was immense, our vehicles met with astonishing force.”

The combined speed was nearly 170 km/h.

Taylor was straight out of the vehicle, arresting the understandably stunned Asling.

Through Fear and Fire, John Taylor’s memoirs.

It was rumoured an SOG officer serenaded Asling with the gang’s signature tune,We’re in the Money.

I asked JT if it was true. “I heard that,” he answered with a straight bat. “But I don’t know who it was.”

In the review, legendary SOG veteran Bruce Knight, who was part of the Tullamarine operation, applauded the action to smash into the getaway vehicle. “Knighty said, ‘If you’re going to park ’em, park ’em good,’” says Taylor.

One of the sad things about policing is that many cops leave the job bitter, burnt out and a little lost.

Having climbed six of the Seven Summits (Mount Vinson in the Antarctic is the exception), Taylor chose to kayak across Bass Strait (never mind that he had hardly ever been in a kayak).

“I loved my time in the job,” says Taylor. “It went so fast, and I have no regrets.”

Now he doesn’t waste time looking back. “I don’t miss work at all.”

Through Fear and Fire, by John Taylor with Heath O’Loughlin, is published on July 1.

Most Viewed in National

Loading