By Graeme Turner

June 29, 2025 — 5.00am

There is a misconception about what it is like to work as an academic at a university, which imagines it as a place of privileged and leisured reflection. It’s a rosy view lately encouraged by the mini-genre of television and film depictions of academic life, many of which romanticise it (The Chair, say) or simply reinforce outdated stereotypes (Lucky Hank).

So, let me offer a reality check by presenting a series of snapshots of what it’s actually like for many who choose to pursue a career in academia. These snapshots are composites I have built from actual scenarios I have witnessed, but they are not portraits of the experience of any one specific individual. I am sure, though, that any academic who reads this will recognise something of themselves or their colleagues in more than one of these snapshots.

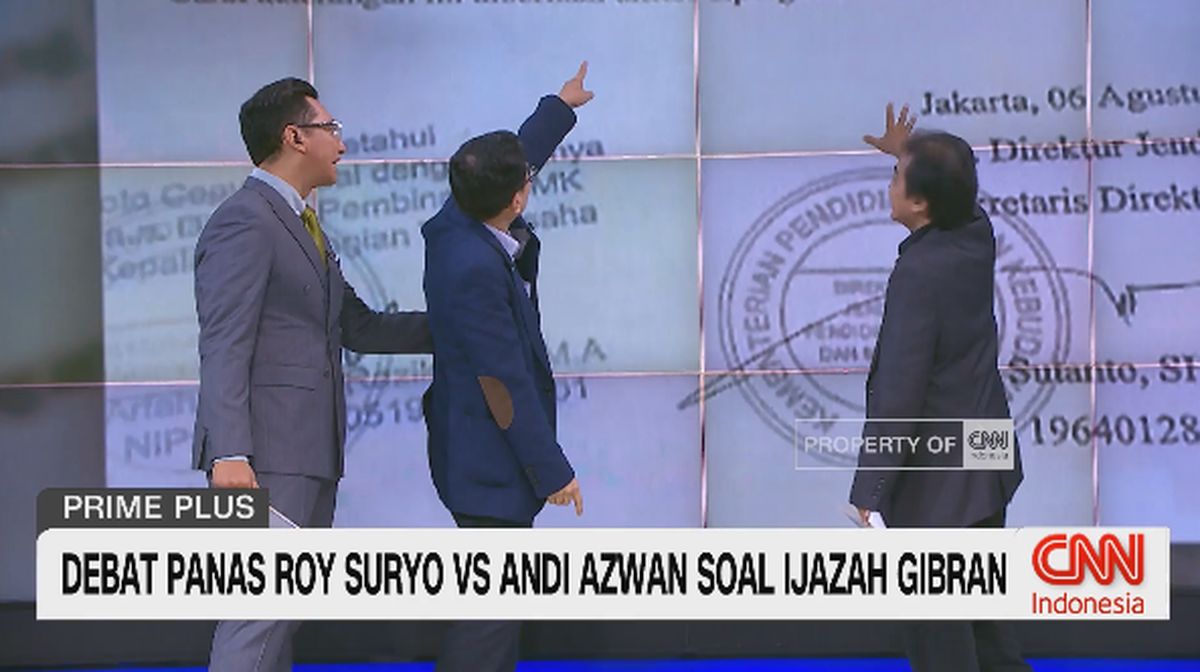

Sandra Oh is the head of the English Department at a minor Ivy League college in The Chair.Credit: Eliza Morse/Netflix

Let’s start with Jane, who has just graduated with her PhD in Australian history from a Group of Eight university. She has been submitting applications, unsuccessfully, for a permanent university position for more than two years. She has published a book from her PhD already. It has attracted strong reviews and even a shortlisting for one of the state premier’s non-fiction awards. But no jobs are advertised in history at the moment, and the field is shrinking. Teaching in history has largely contracted to the Group of Eight, and staffing numbers there have declined by 8 per cent in the last six years. Nationally, enrolments in history over the same period have declined by almost 23 per cent. Since Jane’s field is Australian history, there is little possibility of finding a job outside Australia.

Jane has some sessional tutorial work, but it is at two universities on opposite sides of the city teaching different historical periods. The work involved amounts to more than would be asked normally of a full-time member of academic staff, but Jane needs the money. The casual appointments at both universities commence a week before the start of semester and conclude at the end, so there is no income from teaching for up to four months of the year. As a casual staff member, she doesn’t have an office, so consultations with her students must take place in spaces she arranges herself. To appear like a good citizen and thus a prospect for future appointment, Jane has taken on the management of a first-year course that enrols 200 students, and so the administration (and email) load is significant. This is in breach of the mandated conditions for casual employment, but Jane is prepared to wear this.

Jane has applied for an Australian Research Council (ARC) early career fellowship, but the success rate for applications in the humanities and creative arts is sitting at 20 per cent. In 2023, there was only one successful applicant nationally from history, although there were three in 2025. Jane is trying to get some research done, but the combination of her teaching load, the time spent commuting across town, and the need to earn extra income to cover the gaps in her academic earnings, as well as to keep applying for grants and jobs, impacts on what she can achieve. Despite the time she has invested in getting this far – eight years of study, plus two years of part-time teaching – and despite her passion for the job, she is now reluctantly accepting that she will probably have to look elsewhere for employment. If nothing has changed by the end of this academic year, that is what she will do.

Now let’s meet Stephen. He is a lecturer in a humanities and social sciences faculty within a Group of Eight university. He has a PhD from a well-ranked American university, his first book is with a respected academic press, and he feels like he is getting on top of his teaching. Stephen enjoys working with most of his colleagues, but everyone seems pretty intensely focused on their own careers, so there isn’t much opportunity for collaboration or even conversation outside formal meetings. There is quite a bit of administrative work to do around the teaching, but there is also a steady procession of internal performance audits – classes must be surveyed regularly, student grading must be moderated, the annual performance appraisals involve substantial preparation, and promotion is a whole other matter.

History is only taught at the G8 universities.Credit: Sam Mooy

Senior staff at Stephen’s university keep telling junior academic staff they need to generate more “impact” from their research and do more “engagement” with industry and the community. Managerial exhortations like these are pointless since Stephen is flat out just trying to deal with the basic demands of doing the job. There is pressure to publish his research in high-quality journals, but they can take many months to deliver a decision on your submission and the convention is that you can only submit your article to one journal at a time. Even once accepted, it can take years for a submission to make it to publication.

There is constant pressure to win external grants, but no one seems prepared to acknowledge that, for most junior staff, this is simply an unrealistic expectation. In the humanities, there is only one central funder of research, the ARC, and its basic research grant program, Discovery, has a success rate of less than 19 per cent. Given that the track record of the applicant generates 35 per cent of the assessment score, the scheme is effectively skewed away from early career researchers, and they have very little chance of being part of that 19 per cent. There is some strategic research money at Stephen’s university, but pretty much all of it goes to the STEM disciplines: science, technology, engineering and mathematics.

Stephen is finding it harder to enjoy his teaching. Class sizes continue to rise, the administrative load has increased, and there is an expectation that staff are available 24/7 via email, whenever the student needs them. Attrition rates among domestic students are stubbornly high (around 30 per cent). With the increased enrolment numbers, it is inevitable that many students have turned up for the wrong reasons and end up regretting their choice.

A large proportion of Stephen’s undergraduate students, and a majority of those in the graduate classes, are international students, and many of them have inadequate command of English. It is not uncommon for students to use a translation app in class to understand what is being said. In the large undergraduate classes, which are offered online as well as in person, attendance can be poor. One of Stephen’s classes has 200 students enrolled but on occasion he has fronted up to find as few as 10 in attendance. The influence of artificial intelligence (AI) on written assignments has increased dramatically. In the last assignment Stephen marked, he estimated that something like 75 per cent of the class were covertly using ChatGPT to write their essays.

Fewer undergraduates are turning up to class in person.Credit: Wayne Taylor

As a consequence of all of these influences, the teaching experience is becoming increasingly unsatisfying. So Stephen has decided to make a move. He has been invited to apply for a position in a prestigious research institute in Europe (there are no equivalent institutes in Australia), and that is where he sees his future.

Finally, let’s see how things look for James, who is at the other end of his career. James is the head of a social sciences school in a metropolitan 1970s-era campus. He has been a head of school for three years, as part of a five-year term. He had a solid but not stellar research career previously, and is a successful and popular teacher. The skill sets he developed as a researcher and as a teacher are of limited use to him in this management role, either in dealing with his own staff or in “managing up” with more senior administrators.

James has responsibility for managing a permanent academic staff of 25, a support staff of six, and a fluctuating number of casual sessional teachers, and he must be available, in theory, to every one of the 2000 students enrolled in the school’s courses. The shift into administration was not something he particularly desired. As a senior member of a school with a rotating elected headship, it was simply his turn to take on this responsibility. It is disappointing for him that now he has little time for his own research and has difficulty fitting in even the small amount of teaching he has been keen to retain. At least he has been able to continue supervising some of his graduate students.

The budget for James’s school has been subject to successive cuts that have impacted his capacity to make the appointments he needs to service the course offerings. Even when staff have resigned and moved elsewhere (and this is now happening a lot), it has been difficult to secure approval to make a replacement appointment when the required “business case” demands projections of sustained levels of enrolments and secure funding. As a result, even though the enrolment figures have been relatively stable, his staff numbers have shrunk. Reluctantly, and notwithstanding his sensitivity to the exploitative nature of casual appointments, he has made numerous casual appointments to fill the gaps so he can at least put someone in front of the classes.

Bob Odenkirk in Lucky Hank reinforces an outdated stereotype.Credit: Stan

While James has almost no control over the size of his budget, he is regularly criticised by members of his staff for not doing better at generating funds for the school. At the same time, there is pressure from above on a range of institutional imperatives. Even though many of his staff are not likely to be competitive in pursuing ARC grants in the present circumstances, for instance, his superiors insist that he require them to submit applications nonetheless. James agrees to do this, but in some cases, he actually just doesn’t bother.

James’s situation is typical of heads of school across the university in that they are being squeezed from both sides. They are the target of criticism from their own staff for the consequences of their underfunding as well as pressure from above to do more with the less that is given. It is a thankless and stressful role, with very little opportunity to make things better for staff. If he doesn’t burn out along the way, James intends to serve out his term, take his accrued long service leave, and then move as quickly as possible towards an early retirement.

In each of these snapshots, the academic staff member has done everything that has been asked of them to become a productive contributor to the sector. But none of them can see a future for themselves within the contemporary Australian higher education system. What I have tried to highlight here is precisely the lack of hope in the future, the sense of resignation in response to institutional change they have no capacity to reverse, that is now firmly embedded in the sector’s workforce. It carries disturbing implications for the future of our higher education system.

Loading

This system is more than just an industry. It is a central location for the production, preservation and dissemination of knowledge, for the maintenance and investigation of a cultural heritage, and for the building of a civil society. As the Australian university has increasingly emulated what it thinks of as the practices of commercial business enterprises, it has distanced itself from these kinds of purpose. Along the way, it has also distanced itself from the ideals, capacities and aspirations of many of its academic staff. They are left without a home, forced to find ways to do what both Peter Fleming and Hannah Forsyth, riffing on Bill Reading’s classic 1996 critique, The University in Ruins, have described as “dwelling in the ruins”.

Broken: Universities, Politics & the Public Good, published by Monash University Publishing as part of the In The National Interest series, is available from 1 July 2025.

Start the day with a summary of the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up for our Morning Edition newsletter.

Most Viewed in National

Loading