Opinion

December 23, 2025 — 5.00am

December 23, 2025 — 5.00am

On December 28, war-torn Myanmar will go to the polls. In a way.

No one really believes the long-promised elections will be free, fair or even close to representative.

Illustration by Joe BenkeCredit:

“Sham”, actually, is the word that keeps popping up.

Ballot boxes won’t appear nationwide, of course; only places controlled by the despised military regime and its warlord partners.

Reports have emerged recently of junta types going door to door in Mandalay leaning on would-be voters. Some citizens have also been arrested for uncomplimentary social media posts.

But even if the conclusion is foregone, is there a world in which the elections could in some way lead to a breakthrough in soothing almost five years of Myanmar’s latest iteration of civil war?

Maybe, just maybe, says Morgan Michaels, a Myanmar expert at the International Institute for Strategic Studies, a think tank.

Firstly, though, it’s important to know that the military is headed by a bumbling and ruthless general. He is Min Aung Hlaing, a 69-year-old career army officer with a reputation for talking instead of listening.

Since taking power from the democratically elected government of Aung San Suu Kyi in a February 2021 coup, Min Aung Hlaing and his cronies have busied themselves wrecking the economy, overseeing huge territorial losses, conscripting destitute young men, locking up and torturing political nuisances, and bombing opposition groups and civilians.

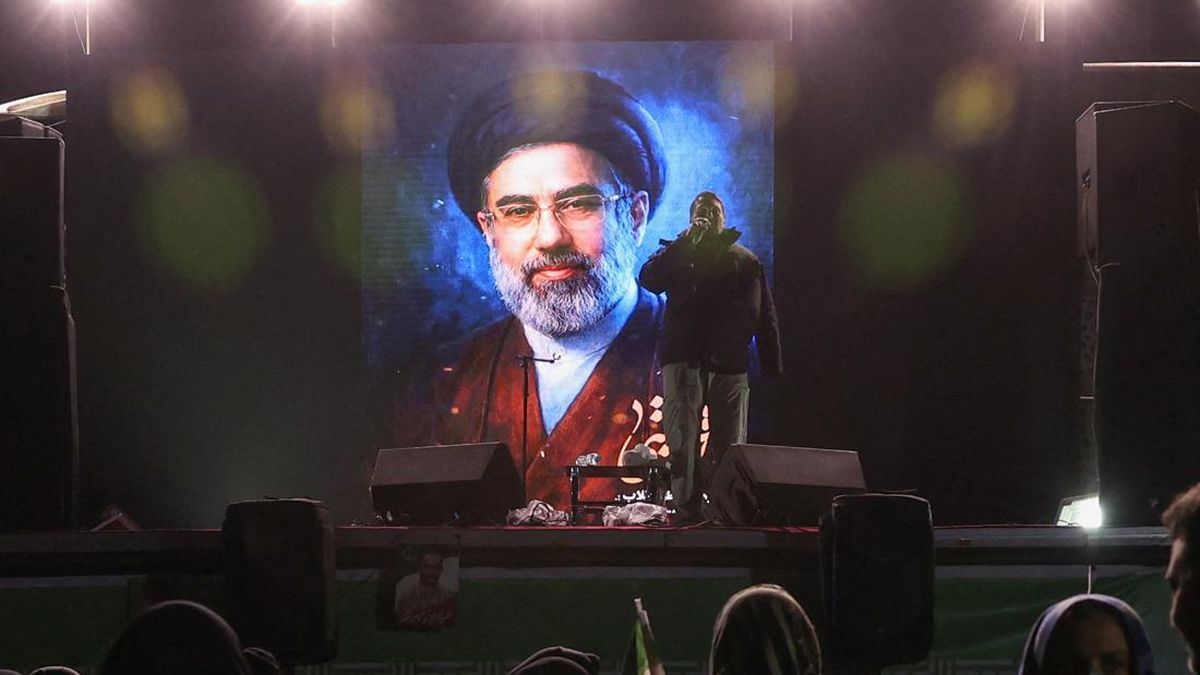

Myanmar junta leader Min Aung Hlaing.Credit: AP

The regime’s multi-front war against myriad well-equipped ethnic and peoples’ resistance armies has killed tens of thousands of combatants and civilians – more than 15,000 this year alone, according to conflict tracker Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED).

Loading

In one of its latest atrocities, the junta’s fighter jets bombed a hospital in Rakhine state, killing at least 33 people, including patients and health workers, according to health and medical agencies. The World Health Organisation said it was the 67th verified attack on a health care service in Myanmar this year.

On the evening of December 5, an airstrike on a tea shop in Sagaing region, a resistance area, killed 18 people watching a football game.

The NLD’s figurehead Aung San Suu Kyi, meanwhile, remain missing in Myanmar’s prison system alongside thousands of others.

And so the junta is toxic in just about every country other than Russia, China and Belarus, its arms dealers. Even the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), of which Myanmar is a member, does not invite the military leadership to summits.

Min Aung Hlaing, therefore, is desperate for his regime to be seen as legitimate, and it believes elections – scheduled in phases rolling into January– are a means to that end.

With political opponents in the voting areas either in jail, exile or barred from running, the generals, via their proxy, the Union Solidarity and Development Party, will declare both victory and a popular mandate.

Classic stuff.

Protests against Myanmar’s military after the 2021 coup led to thousands of arrests.Credit: AP

After the coup, remnants of the forcibly dissolved NLD and some ethnic leaders formed the shadow National Unity Government. It has asked the world to treat the junta’s elections as a fraud.

Australia has joined this chorus, saying the vote could lead to “greater instability and prevent a peaceful resolution”. In effect, entrenching military rule under the guise of a democratic process.

“Australia will continue to urge a peaceful transition of power to a democratic civilian government that reflects the will of the people,” the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade said in a statement this month.

But there is a school of thought that suggests the elections might just shift the dial on something. What that is, we don’t know. But something, anything, may be better than nothing.

Loading

Michaels, who produces regular and highly detailed conflict analysis for IISS, says some international stakeholders privately view the upcoming vote as an opportunity to rattle the status quo.

To what extent might depend on whether Min Aung Hlaing takes the presidency, keeps his role as the military’s commander in chief, or engineers both titles onto his desk.

“In any case, the leadership dynamic will change,” Michaels says.

“There’ll be new people in different roles, plus there’ll be a parliament. Will the parliament be representative? No. But there’ll be a couple of minority parties. And the USDP, which is the military’s proxy party … relationships between the military and the USDP have really soured in the past year, year and a half.

Aung San Suu Kyi with Min Aung Hlaing in 2016.Credit: AP

“So at a minimum, at a minimum, there will be a new leadership dynamic, and there will be some marginal compromise or bargain making going on, and then the hope is that that creates some change.”

Could that mean pressure on senior general Min Aung Hlaing? Possibly. He said to be on the nose with some in the military in part because of the territorial gains made by resistance groups. The junta has since taken back some of that ground, and the war is presently in a kind of stalemate, Michaels says.

Some of the junta’s rebound is owed to the economic and military support offered by China, which equates regime collapse with state collapse. It does not want heightened uncertainty along swathes of its southern border.

Australia emphasises ASEAN’s central role in bringing peace to Myanmar. But so far, the regional bloc’s limp efforts – namely the so-called Five-Point Consensus, which the junta agreed to but ignores – have come to naught.

Loading

Min Aung Hlaing wants regional legitimacy, but excluding him from regional summits seems like a hit he’s okay with taking. In any case, Chinese President Xi Jinping has welcomed him to Beijing. He has also met with Indian prime minister Narendra Modi and Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Belarussian strongman Alexander Lukashenko late last month became the second leader to visit Myanmar on the invitation of Min Aung Hlaing (the other one being long-time Cambodian ruler Hun Sen, another despised authoritarian).

Some of these characters might not engender a great deal of upwards thrust on the ledger of global standing. On this front, the biggest gift has come from none other than the USA.

In an extraordinary show of ignorance, racism, heartlessness or all of the above, President Donald Trump’s Secretary of Homeland Security Kristi Noem last month told thousands of Myanmar citizens living in the US that they would no longer be eligible for protection visas.

According to her, the situation in Myanmar had “improved enough that it is safe” for them to go home. Naturally, the junta loved it.

Among Noem’s stated reasons for America’s change of mind on Myanmar? “Plans for free and fair elections”.

Zach Hope is the South-East Asia correspondent for the Sydney Morning Herald and the Age.

Most Viewed in World

Loading