Rodrigo Zavaleta worked across four Merivale venues for five yearsCredit: Janie Barrett/Fiona Bianchinotti

Fair Work is investigating Merivale following fresh claims the hospitality giant underpaid and exploited vulnerable workers, including eight migrant chefs who say they were recruited from Mexico under false pretences.

The Fair Work investigation follows allegations by this masthead, Good Food and 60 Minutes that Merivale is still ordering staff to work more than full-time hours, as the company plots a huge expansion into Melbourne through a $55 million, 11-storey complex in the CBD and a new spa, hotel and nightclub in the heart of Sydney.

“The Fair Work Ombudsman is investigating Merivale Hospitality Group,” a spokesperson said. “We encourage any workers with concerns to contact us directly for assistance.”

The Fair Work probe has been launched just months after Merivale agreed to settle a $19.5 million wage theft class action with hundreds of workers without admitting fault. Lawyers for Merivale and billionaire owner, Justin Hemmes, said that the company “defended the claims in the litigation, at all times vigorously denying that any underpayment occurred”.

The multi-billion dollar company behind hatted restaurants Mr Wong, Mimi’s, and Fred’s filled industry-wide skill shortages by partnering with a recruitment agency to encourage migrant chefs to give up the life they knew in exchange for something better: a four-year working visa in Australia, where they would be paid higher wages, work shorter hours, and have the opportunity to advance their careers.

Instead, chefs said they worked upwards of 60 hours each week without penalty rates to cover staff shortfalls in high-pressure kitchens where they allegedly suffered discrimination and bullying.

For years, they kept quiet, fearful of Merivale’s ability to withdraw their sponsorship status and desperate to stay in the country they had fallen in love with. Now, having left the company, they’re finally speaking out.

Dream turns to nightmare

For skilled Mexican chefs seeking a better life, Merivale was the perfect sell. The hospitality giant promised greater salaries, glamorous staff parties and the opportunity to work alongside world-renowned executive chefs like Dan Hong of Mr Wong. Best of all, the company would sponsor the chefs’ working visas, allowing them and their families to live in Australia for up to four years, and putting them on a path to permanent residency.

“Everything sounded perfect,” said one female chef. “But it was a nightmare.”

Within weeks of arriving in Sydney, the woman found herself crying in the bathroom of her two-bedroom apartment, where she lived with six other Mexican migrants. She had just finished another 15-hour shift - without breaks - at a Merivale restaurant.

“We were all desperate,” she said. “I had this feeling like, ‘Why did I do this?’.”

A screenshot from an Alliance Abroad promotional video about life in Australia.Credit: Facebook

Merivale executives had flown to Mexico on recruitment missions to scoop up skilled chefs to fill chronic labour shortages in Australia in 2017 and 2018. The mother-of-three said she was one of about 100 vetted candidates to attend Merivale’s Mexican showcase, held in partnership with recruitment firm Alliance Abroad.

Merivale and Alliance Abroad hosted mystery box cooking challenges to whittle down the candidates, promising them a future filled with sun-drenched beaches, surf lessons, and kangaroos.

The applicants were told they were joining “one of the best companies in the world,” known for its high-end restaurants and extravagant fit-outs in 90 venues across Australia, including Totti’s, the Coogee Pavilion and Queen Chow. Among the crowd were chefs seeking better wages, improved working conditions, and travel opportunities.

The woman just wanted a safer life for her children. In her home state in Mexico, cartel violence had escalated to record highs in 2017. Months before she saw the Alliance Abroad ad for Merivale on Facebook, a mass grave containing 250 skulls had been uncovered outside one of its major cities. “My teenage cousin was kidnapped and killed,” she said. “It was scary. I didn’t want that for my kids.”

Inside Mr Wong in Sydney’s central business district.

Still, the stark disparity between her new reality and the fun, friendly workplaces portrayed in Merivale’s promotional video came as a shock. In her darkest moments, she considered returning home to the cartel-fuelled violence in Mexico rather than staying in a Merivale kitchen.

This masthead and Good Food have spoken to eight former Merivale chefs recruited from Mexico who claim they were overworked, underpaid and racially discriminated against while working for the hospitality group, which owns property worth an estimated $3 billion. Some requested anonymity to protect their future employment.

The claims are the latest in a long list of allegations against one of Australia’s largest hospitality companies. On Sunday night, a joint investigation with 60 Minutes revealed further claims of exploitation of Merivale workers, fuelled by a business that courted politicians and private club members with links to organised crime that has seen the company become one of the country’s most influential hospitality operators.

Merivale has denied all allegations against it.

‘No one gave a f–k about the employees’

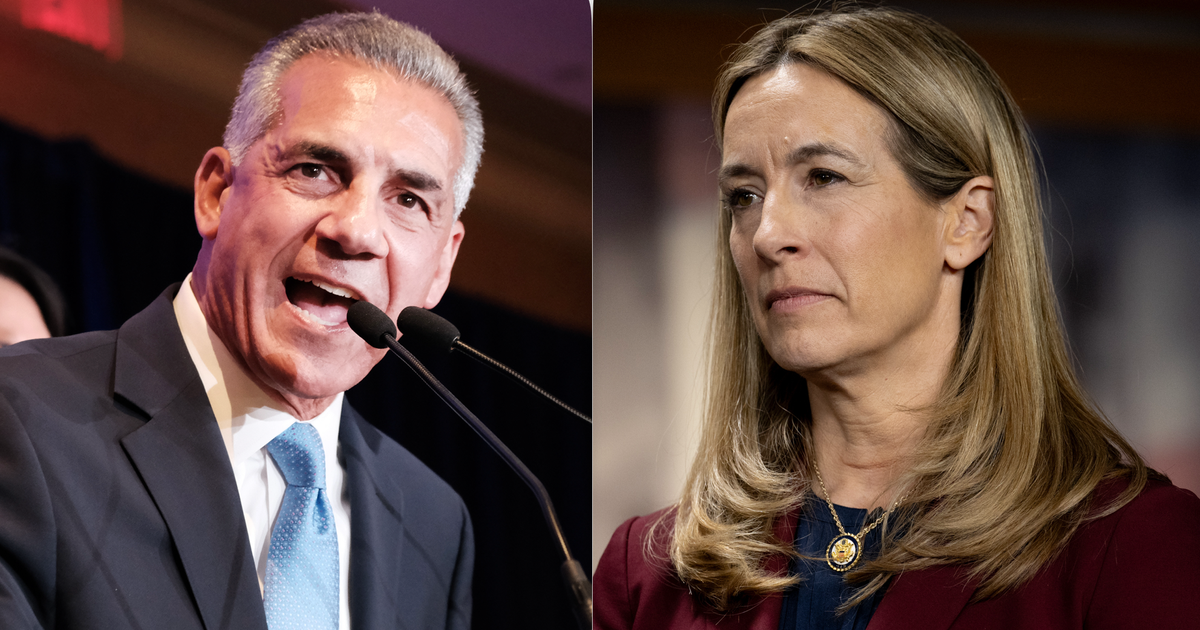

Mexican chef Rodrigo Zavaleta, who worked across four Merivale venues for five years, including Hotel Paddington, said the cost of produce was more important to the company than delivering on the vision promised to migrant workers.

“[Merivale] preferred to exploit humans instead of vegetables,” Zavaleta said. “It was clear that no one gave a f---k about the employees.”

Chef Rodrigo Zavaleta worked at Merivale for five years. Credit: Janie Barrett

The former Merivale chefs said they were bullied and pressured to work through physical injury – but in each case, they said they felt exploited by the hospitality empire, which they were fearful could revoke their working visa sponsorship at any time.

Another Merivale chef, Rodrigo Santos, said he would regularly work up to 65 hours in one week at Hotel CBD.

“Then at the end you see the roster, see the timesheets, and it says 40 to 45 hours, and you’re like, ‘Oh, I’m a sponsor, so maybe that’s normal’. He said that later on, he started looking into it, and realised it wasn’t.

In 2021, Santos was transferred to The Paddington, Merivale’s neighbourhood pub on Oxford Street. There, a small team of chefs would serve up to 350 customers a day while sometimes working weeks of up to 60 hours - almost double the maximum number of hours for full-time workers in Australia.

According to the Fair Work Ombudsman, an employer must not require staff to work more than 38 hours in a week, and no more than 11.5 hours in one day. Overtime under the Restaurant Industry Award must be “reasonable”, considering risk to employee health and safety, and paid at penalty rates.

“I didn’t know I was allowed to say no,” Santos said. He explained how some senior staff used his fear of deportation to the company’s advantage, prefacing requests for overtime with, “If you want to stay here,” or “If you want to keep your visa”.

“[New employees would come in, realise how bad it was, and] be like, ‘Why don’t you leave?’ and we would be like, ‘Well, we can’t’.”

“They knew they could treat people like shit because no one was going to have a confrontation with them,” said another chef. “They knew we were on a sponsorship, and if we said anything, they [could] fire us, and well … what could we do?”

Lawyers for Merivale have denied the company targeted migrant workers, stating the allegation was “baseless and offensive”.

The recruitment missions

Merivale’s overseas recruitment drive was necessary to combat industry-wide staff shortages, human resources representative Ash Campbell told Hospitality magazine in 2018. The company has also recruited from countries including Malaysia, Indonesia and Nepal.

Campbell, along with executive chefs Dan Hong (Mr Wong, Queen Chow), Ben Greeno (Fred’s, Hotel Paddington) and former executive chef Nick Imbragen (ex-El Loco), travelled to Mexico City to oversee the series of one-on-one interviews and mystery-box cooking challenges. There is no suggestion of any wrongdoing on the part of Hong, Greeno or Imbragen.

Merivale chef Dan Hong on one of Merivale’s recruitment missions to Mexico. None of the chefs pictured spoke with this masthead for this story, and it is unclear if they ever made it to Australia.There is no suggestion of any wrongdoing on the part of Hong.Credit: Instagram

Successful chefs signed a $US8500 ($13,000) contract with Texas-based recruitment firm Alliance Abroad International. The contract said the $13,000 for their Cultural Support Program included “relocation support for a period of four years”, but chefs said support was limited to a brief hostel stay and visa processing. It did not include flights. The total cost is more than four times the price of the $3115 skilled visa for chefs, according to the Department of Home Affairs. Alliance Abroad said its “comprehensive orientation program” also included pre-departure workshops and arrival briefings.

But when the chefs arrived in Australia, they said it was a far cry from the glossy images they were promised in Mexico.

“When we arrived in Sydney, it was just three days in a hostel, and then you had to find a place to live,” said Santos. “It was really hard to secure a lease because of no background, no bank account and no help.”

The $13,000 fee was automatically deducted from their bank accounts during the first 18 months in Australia.

Most were employed as a chef de partie and paid minimum wage, starting at around $54,000 per annum in 2018.

It was a “life-changing amount of money” compared to what they were earning in Mexico, said another chef. Then he did the math: if they worked between 13 and 15 hours each day, without paid overtime, their salary would be less than minimum wage.

The other chefs scoffed at the suggestion: “Well, if we worked that many hours, it would be just like Mexico,” one wrote. “The contract states the maximum number of hours is 52 per week … [and] it’s too late to get upset, anyway.”

In reality, the long hours were brutal, sometimes stretching up to and beyond 52 hours a week at restaurants such as Totti’s Bondi, Uccello, and Mr Wong, said sponsored staff. It’s alleged they were only paid for 38.

Former Paddington and Totti’s Bondi chefs said they often worked without breaks, despite senior staff recording - or asking them to record - breaks on their timesheets.

Alliance Abroad International had misled them, alleged three chefs, two of whom suspended support program payments within the first year. Where was the competitive salary, the work-life-balance, and agency support when things went wrong?

Alliance Abroad global marketing director Anna Downes said “a small number of chefs raised concerns regarding rosters and overtime”, which were then escalated to Merivale’s human resources team.

“[Merivale] advised us that the matters were being addressed internally,” Downes said.

“Any suggestion that we condone or facilitate the mistreatment of migrant workers stands in direct opposition to the values, safeguards, and global standards that underpin everything we do. We strongly reject any claim that we knowingly facilitated such exploitation.”

Merivale has denied knowledge of any such complaints, and maintains the company complied with its legal obligations to employees.

Mr Wong, the two-hatted jewel in Merivale’s hospitality crown, was considered the “worst” place to work in The Ivy precinct, said a female former chef. In another group chat of sponsored chefs, they described Mr Wong as a monster of a venue – constantly busy, with a weekly roster which sometimes had chefs working double shifts most days.

For her, that meant arriving at 10:30am, taking a break at about 5pm for three hours, then returning until 2am. She said staff slept side by side on daybeds in the break room between shifts.

“The sofas were super old,” she said of the couches. “You just had to find a space and sleep next to someone.”

Merivale said staff rooms were often used by staff to nap during their breaks or before or after their shifts. “Couches are provided within staff rooms for amenity and comfort,” Merivale’s lawyers said in a statement. “To link staff who nap in the staffroom to some form of nefarious behaviour by Merivale towards its employees is absurd.”

Those who struggled with speaking or understanding English, or used different cooking methods, were allegedly mocked or laughed at. Zavaleta recalled some chefs referring to their migrant counterparts as “the Mexicans”.

“I would remember listening to one of the team leaders regarding us [as], ‘the Mexicans’, he said. “The Mexicans should do this, the Mexicans should do that.”

The chef from Mr Wong said they rarely complained: “We were all fighting for the permanent residency [PR] … and there was an implicit understanding that if you wanted PR you needed to say yes to everything,” she said.

Chasing the ‘golden ticket’

Permanent residency became the “golden ticket,” incentivising staff to keep quiet, work hard and rise through the ranks, said another former chef who worked at fine-dining Merivale restaurants such as Uccello. “We saw permanent residency as a prize Merivale gave you – a prize you had to earn.”

It fostered an environment of fierce competition, he said, describing some kitchens in The Ivy precinct as a “dog fight” where chefs had to prove they were better than their colleagues by shouting at them.

“It was the hardest time of my life,” said another chef who spent time at a hatted restaurant in The Ivy precinct. He was used to the cut-throat world of fine-dining kitchens, having worked at a Michelin-starred restaurant in Mexico. But nothing compared to Merivale.

Chefs estimate that more than half of their Mexican colleagues left the company before receiving permanent residency. Merivale has denied knowledge of any migrant chefs returning to their country of origin due to workplace conditions.

One chef, a single mother-of-four recruited from South-East Asia, said the long hours and low pay eventually pushed her to find an alternative workplace willing to sponsor her.

“I explained to my kids that we can’t go back, and you need to fight for it, to stay here … [but] it was too much,” she said. She remembered the school events she missed, and the time she couldn’t leave work to comfort her injured child on an ambulance ride to the hospital.

“I just worked, worked, worked, all the time … but it wasn’t enough to [cover the cost] of the kids,” she said. After tax, rent and the Alliance Abroad fee were deducted from her weekly salary, she estimated she was left with around $300.

Alliance Abroad and Merivale are preparing to return to Mexico for another recruitment drive. This month, the agency emailed the Mexican chefs they’d recruited for Merivale in 2017 and 2018 to request testimonials that would “encourage other talented chefs in Mexico to follow in [their] footsteps”.

Staff warned to work

In late 2019, hundreds of staff who alleged they had been systematically underpaid for years by the hospitality giant filed a class-action lawsuit. When migrant workers were given the option to sign onto the lawsuit and receive compensation, many declined for fear of losing their sponsorship, despite the promise of confidentiality.

Alliance Abroad said it was unaware of the class action lawsuit until it became public through media reporting.

Merivale agreed to settle the $19 million class action without admitting fault in November. Lawyers acting for the company said Merivale has at all times vigorously denied underpaying its staff, and maintains the claims are false. The settlement prevents any signatory from making statements to the contrary.

But new documents show some staff are still being told to work more than full-time hours.

Internal emails reveal that in September, Merivale executives were forcing full-time staff to work 45 hours per week by warning to “pull lists of staff members” who were not hitting those hours.

A payslip from May shows a staff member being paid for a 38-hour week, despite a separate time card showing they registered 60 hours that same week. Some staff earning more than the award of $78,000 do not get any overtime until they have worked a sixth or seventh day in a row.

The staff member, who worked shifts of up to 14 hours, alleges they had 60 hours squeezed into five days.

Merivale denied these claims, stating its “employees receive pay that meets or exceeds the relevant award entitlements”.

But the punishing work conditions took a heavy psychological toll, fuelling depression and anxiety among chefs.

“Every day felt like a test,” Santos said. “People [would] tell you you’re wrong, you’re shit, whatever, so you started to [adopt] that kind of mentality.”

It took a plea from a concerned colleague for management to cut down their hours. For some chefs, conditions slowly improved after the COVID-pandemic. The staffing shortage had become dire, and Merivale fought to retain staff with promotions, shorter work weeks and the occasional overtime payment.

Some venues became known among employees as “less complicated” than others, said one chef from Totti’s Bondi, who received regular annual pay rises in line with the award.

Among the chefs who stuck it out and received permanent residency, one said he is traumatised, some suffer from ongoing physical injuries, and another is in therapy.

But, free from Merivale, they are happy.

“I’m glad I’m here,” said Zavaleta, who left the company in 2023. “[I just wish] they had told me: ‘Hey, we’re going to treat you like shit. We’re going to give you shit. But in five or six years, you’re going to become a resident of this beautiful country.’

“F--k it, I’ll take it, I’m down. But they didn’t deliver it like that. It was all smoke-screens and make-believe.”

Start the day with a summary of the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up for our Morning Edition newsletter.