Victoria could reverse its escalating trend of violent youth crime within a few years if it adopted the Scottish approach of introducing “a thousand small sanities”, say two of that country’s youth justice leaders.

Crime statistics released last week show children aged between 10 and 17 are committing almost two-thirds of Victoria’s robberies and half of all aggravated burglaries, and that Victoria Police’s taskforce on youth gangs has arrested 494 gang members a combined 1657 times in the past year.

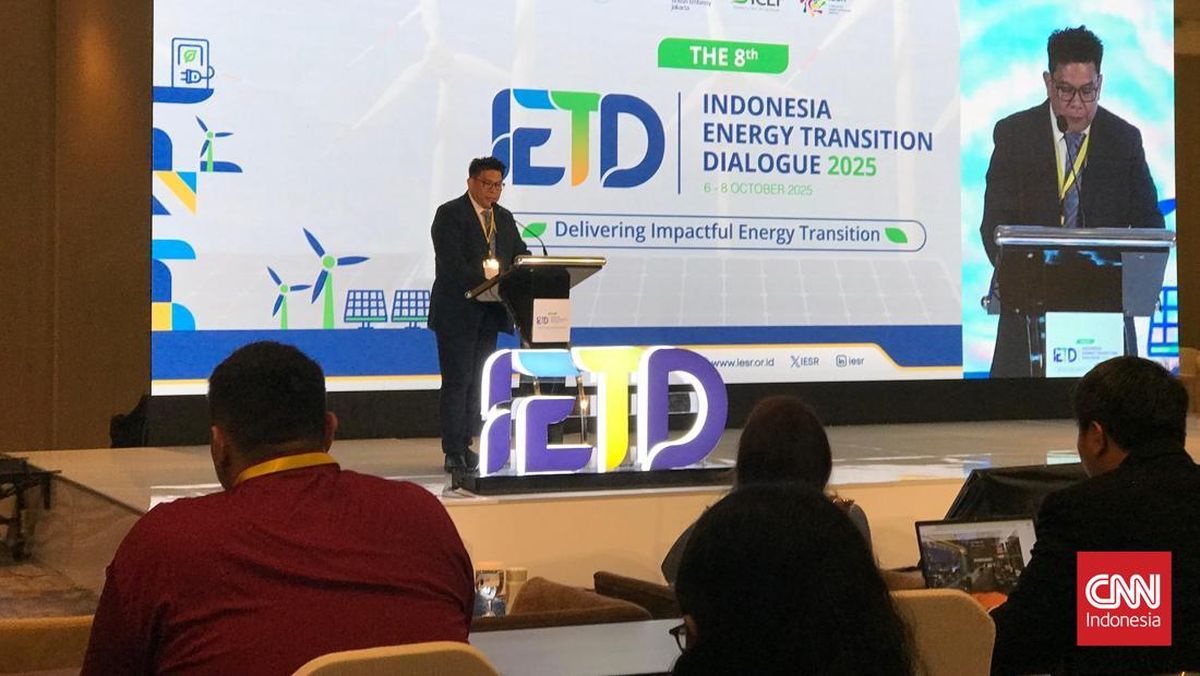

Karyn McCluskey, a former co-director of Scotland’s violence reduction unit.Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

But Scotland’s transition from the homicide capital of Western Europe to having no under-18s in jail provides a potential model for reform, says Karyn McCluskey, the founder of the country’s violence reduction unit.

In the early 2000s in Scotland, knife crime was prevalent and best illustrated by the number of victims sporting a “Glasgow smile” – the descriptor to scars around a victim’s mouth caused by blades.

“We didn’t just have a murder every weekend, we had sometimes two, three and four,” says McCluskey, who oversaw the Scottish Violence Reduction Unit, which helped transform the country’s justice system.

She says the answer was to ignore those who weaponise youth crime for political purposes and start treating the scourge as preventing a public health crisis.

There was no magic bullet. McCluskey and her colleagues engaged with health services, employers, the courts, schools, politicians and the media, to seek early intervention measures and prevent young people starting a life of crime.

Loading

In one memorable intervention, Glasgow police rounded up more than 100 gang members and put them in a courtroom, where the dangers of a criminal lifestyle was highlighted.

Surgeons described the trauma of stab wounds. A mother spoke about the heartbreak of losing her son to gang violence.

“You could see the guys in the back of the court, some of them were crying because whatever harm they were doing, they sort of loved their mums,” McCluskey says.

Police told the young men: “We know who you are, we know where you live and we could come in and kick your doors in.”

Or, officers told the group, the males could volunteer to engage with police and change their behaviour.

The vast majority of hands in the courtroom went up. “We were overwhelmed,” McCluskey recalls. “People said, ‘I’ve had enough of this, I want something different’.”

‘We can fill the jails. I mean, you’ve done it in Australia, we’ve done it in the UK. That’s not what prevents crime from happening. You have to be smarter, and so we did this very public health approach.’

Karyn McCluskeyWhen the Scottish unit began its work, more than 177 youth gangs with a combined 3500 members were operating across Glasgow and, McCluskey says, “We had lots of young people who thought that stabbing someone in the arse was fine.”

After the program’s inception, homicide rates declined almost immediately. From 137 homicides per year in the early 2000s, there were now 57 a year, and in September last year, the last teenager was removed from a jail in Scotland.

“We can fill the jails,” McCluskey says. “I mean, you’ve done it in Australia, we’ve done it in the UK. That’s not what prevents crime from happening. You have to be smarter, and so we did this very public health approach.”

Loading

But it was not easy, she says, “in this environment when everything’s weaponised”.

“We had a few murders, and people would say, ‘Right, this isn’t working. You need to get back to your work and start jailing people’.”

Will Linden, the current deputy head of the Scottish Violence Reduction Unit, says at the time the program was introduced, those behind it thought the country’s crime problems would take a generation to fix.

“It didn’t. It took a few years. We started to see things change as services changed, as policing changed, as the message got out into the community,” Linden says.

If Victoria adopted a program like Scotland’s, it needed support across the political spectrum and from the public, McCluskey says.

Both Premier Jacinta Allan and Opposition Leader Brad Battin are projecting tough on crime approaches. Credit: Various

“You can’t just have all the problem admirers – the ones that wring their hands, and they clutch their pearls ... you actually need to get to the solutions.”

As youth crime in Victoria reaches its highest rate since electronic records began and police are seizing unprecedented numbers of knives, there are worrying similarities between the Scotland of the early 2000s and present-day Victoria.

Crime has become a hot political issue, with both the government and opposition taking tough approaches. Victoria Police Chief Commissioner Mike Bush has backed calls for tougher punishments for youth offenders, but despite police increasingly arresting and charging offenders, crime rates have not fallen.

Loading

In 2024, Premier Jacinta Allan walked back support to raise the age of criminal responsibility to 14 and overhauled bail laws in May to treat accused children the same as adults in serious cases.

Opposition Leader Brad Battin, a former police officer, has repeatedly declared crime is out of control in Victoria.

Battin made a $100 million pledge to grant police more stop and search powers, but has also proposed a boot camp-style program aimed at rehabilitating repeat offenders aged 12-17 if the Liberals win the 2026 election.

Ahmed Hassan, the chief executive of Youth Activating Youth, has spent almost the past decade working with reformed young offenders in Melbourne.

He has seen firsthand the devastation of a young person he has worked closely with slipping back into a life of crime, but has also seen others entirely change their lives’ trajectory when they are given the right opportunity and support.

Ahmed Hassan, youth worker ansd the founder of Youth Activating Youth, based in Melbourne. Credit: Chris Hopkins

“Some of the incidents that are taking place are quite unfathomable,” Hassan says.

“This can’t become the new normal.”

The youth worker says breaking the cycle of reoffending is about setting up the correct support and preventative measures for young offenders before their release back into the community.

These include stable employment and housing, and addressing issues such as mental health and substance abuse.

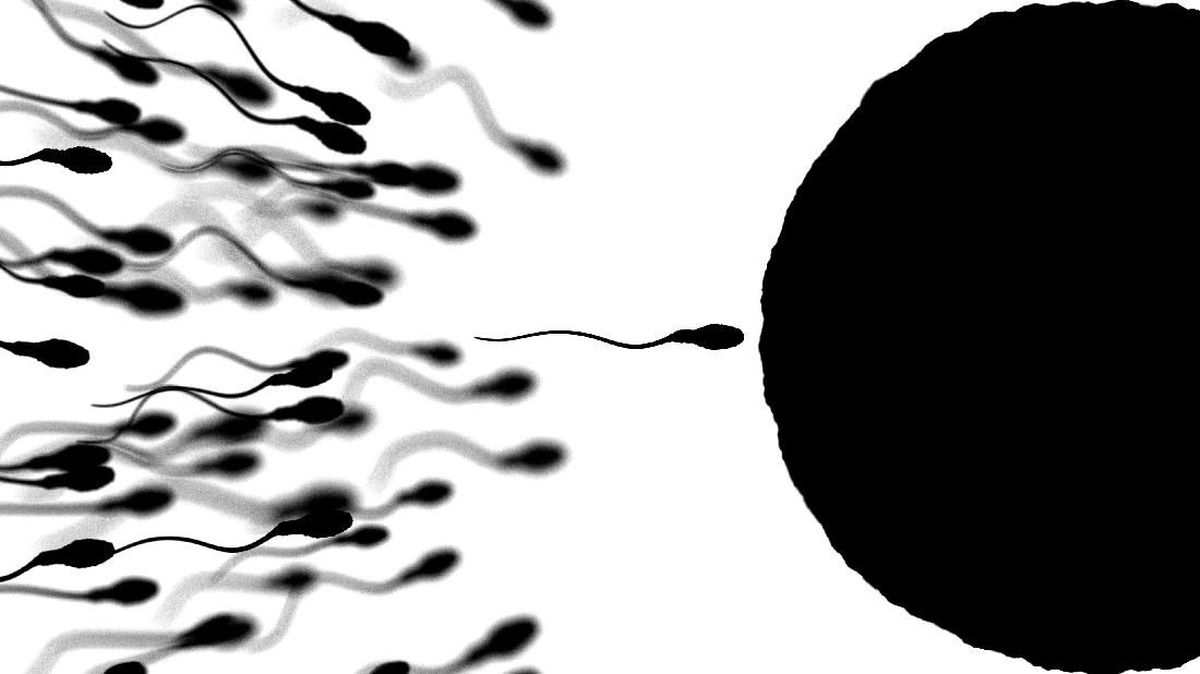

Breaking the cycle of recidivism is the key to reducing crime, experts say.Credit: Illustration: Dionne Gain

“When a young person is released, who they spend time with next is very critical,” Hassan says.

“It can either set you up for good or set you up for bad. A lot of young people go back to what they know if they aren’t given an opportunity to overcome this.”

What Hassan has found to be one of the most powerful ways of breaking the crime cycle is when reformed offenders share their experiences with others.

Loading

Many of the young people Hassan has worked with straight out of the justice system have broken the cycle of disadvantage and crime, and are now employed by Youth Activating Youth as lived-experience mentors and youth workers.

Recently, Hassan saw one youth offender win a premiership with his football club after being released from prison. The young man is now employed as a mentor at Hassan’s not-for-profit organisation.

Hassan says the sporting club became a place where the young man has developed a sense of belonging and self-belief.

A Victoria Police spokesperson said police continued to focus on preventative measures including crime reduction teams across Melbourne and Geelong, who are responsible for engaging with offenders regularly to provide support pathways that encourage rehabilitation.

There are still murders, stabbings and violent crimes in Scotland, but it’s almost unrecognisable from its homicidal past.

“We’ve not eradicated violence,” Linden says. “It’s just at a much lower level.”

“One thing we’ve also learnt is that we can never take our eye off this.”

Start the day with a summary of the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up for our Morning Edition newsletter.

Most Viewed in National

Loading