The house where gunmen Naveed and Sajid Akram spent their last hours in anonymity has been wiped clean. Mattresses on spartan metal frames are stripped, clothes racks are empty and duvets rolled up. Chairs are tucked in behind small, plain desks. The windows are wide open, perhaps in the hope that any evil lurking inside will be blown away by the breeze. Only the bins contain relics of life before clocks stopped at around 6.42pm on Sunday; fast food boxes, delivery bags and an empty Nintendo Switch box.

The men finalised preparations for their hateful attack in a room in this bleak, short-term share house. A fruiterer and an unemployed bricklayer, a father and his son. Their relationship is one of the many unfathomable aspects of this atrocity; a father is supposed to guide his son with love, not accompany him in slaughter. Radicalisation expert Clarke Jones has researched countless extremists over decades, and he has never seen it before. “If anything, the families are the protective factors, the ones who minimise the chances of a young person going out and doing crazy stuff,” he says.

Australians are desperate to understand how the minds of two suburban men could become so warped that they would kill 15 fellow Sydneysiders in cold blood on a summer’s evening, and whether anything could have been done to stop them. It’s too early for that; not even law enforcement has answers yet. But a picture is emerging of how ancient hatreds, insidious extremists and personal grievance can create fertile ground for the kind of barbarism that Sydney witnessed on Sunday.

Bonnyrigg, near Liverpool, is a long way from the Sahel region of Africa, where the remnants of Islamic State have reclaimed territory after the loss in the late 2010s of its so-called caliphate across Syria and Iraq. Residents in this sleepy suburb have no concept of what it’s like to be subject to arbitrary violence by their government – beheaded for watching a music video or having a beer – in the name of Islamic purity, but this is what the Akram men were willing to die for.

During the 2010s, the threat of terrorism related to the brutal Islamic State was almost a nightly story on Sydney news. IS orchestrated attacks in Paris in 2015, which killed 130 people, and it inspired others, such as the shooting of 49 people at an LGBTQ nightclub in Florida. Eleven years before the Bondi attack, almost to the day, Man Monis sealed the doors of the Lindt Cafe in Sydney’s Martin Place and held 18 people hostage in the name of IS.

Hostages flee after police storm the Lindt cafe in the early hours of December 16, 2014.Credit: Andrew Meares

Since its caliphate disintegrated, IS has barely featured in news reporting or threat assessments. But it has never gone away. “‘Defeated’ is not a thing you do to insurgents. The ideas exist forever,” says Levi West, an expert in countering violent extremism at ANU. The Bondi killers’ identification with IS – they had home-made IS flags in their car – and the organisation’s celebration of the murders, has put it back at the forefront of public debate.

Islamic State is reclaiming territory in north Africa and in Afghanistan. But it doesn’t need land to continue its crusade; its instruction in religious extremism and the how-tos of terrorist violence is easily found online. Al-Qaeda, another fundamentalist group, preferred to control terror activity, but IS doesn’t care. It’ll take any brutality in its name. “They don’t even need local cells,” says University of Canberra law professor Sascha-Dominik Dov Bachmann. “You just need a self-radicalised individual.”

Loading

For the past two years, since the vicious attack on Israel that killed 1219 people, the world’s focus has been on another Islamist terrorist group, Hamas. Israel’s subsequent campaign to stamp out Hamas in Gaza, which left tens of thousands of Palestinians dead, has divided the international community. After October 7, there has been a sharp increase in antisemitic attacks against Australia’s Jewish community.

IS and Hamas hate each other. IS terrorism, like Al-Qaeda’s before it, is religious, albeit deeply twisted; it wants to impose its violent version of Islam on the planet and it wants those who do not share its views to die, particularly other Muslims. Until recently, IS has been vague on the issue of Palestine. Historically, it has concentrated on Syria, Iraq, and terror attacks on Westerners.

Hamas’ terrorism is political, in the vein of the Irish Republican Army. It might be a religious organisation, but its purpose is to reclaim territory in the Middle East for a Palestinian state. It wants to destroy Israel and kill Jews. Islamic State thinks Hamas is soft for being willing to settle for anything less than a caliphate, yet it saw opportunity in Hamas’ attack. It revived its pitch that Muslims were being victimised by Israel and the West. That led to a “drastic change in ISIS-inspired lone-wolf attacks”, writes analyst Rita Katz, of the SITE Intelligent Group. “‘Save the Muslims in Gaza by attacking the Jews and Crusaders in the West’, it told them.”

Police outside the Bonnyrigg home of Bondi gunmen Naveed and Sajid Akram.Credit: Sitthixay Ditthavong

In 2016 – the year IS was linked to multiple attacks in Turkey, Belgium and France that killed hundreds – Akram and his wife, who had three children, paid $700,000 for a brown brick, three-bedroom house with a pool in Bonnyrigg.

Akram was born in India, studied commerce at university there, and moved to Australia in 1998 on a student visa. Indian news outlets have quoted Akram’s brother saying his family cut ties with him after he married Venera Grosso, a woman of Italian descent living in Australia, and that he’d repeatedly tried, and failed, to get Australian citizenship.

Naveed would have been about 15 when the family moved to Bonnyrigg, and on the verge of leaving Cabramatta High (he didn’t complete year 12). Old schoolmates told the Daily Mail he was “one of the smart kids”, and never in trouble. “We played basketball until about 5pm most days, and then he would make his way home,” said one.

Naveed emerges on the public record in 2019, two years after US-backed forces seized the last IS stronghold in the Middle East. The Street Dawah Movement, a volunteer organisation that attempts to convert people to Islam outside western Sydney railway stations, uploaded a series of photos and videos of teenage Akram proselytising on the streets of Bankstown. He was chubby-faced and spoke with a lisp. “Guys, spread dawah wherever you can,” he says earnestly, staring straight into the camera. “This will comfort you on the day of judgment.”

Loading

Law enforcement had been watching an IS cell that year with multiple members linked to the Street Dawah Movement in Bankstown. Street dawah is a form of proselytising popular among some hardline Salafi Muslims. It has repeatedly been linked to violent extremists in Australia and overseas (at least seven of the 15 men detained during counterterrorism raids in 2014 knew each other through another street dawah group in Parramatta).

The Bankstown group in which Akram was briefly involved had come to the attention of investigators because of its association with other IS figures who ended up being jailed for terrorism offences, such as Youssef Uweinat (who was convicted for IS recruiting), Joseph Saadieh (who ran jihadist Instagram accounts with Uweinat), and Moudasser Taleb (who attempted to fight for Islamic State in Syria).

ASIO and the NSW Police investigated Naveed for six months because of his association with the others. They concluded he did not pose an ongoing risk, but he was placed on a “known entity management list” – a register of people who have attracted the interest of counterterrorism authorities – in about 2021.

There’s little public record of him since, beyond footage of him sparring at a boxing gym in Moorebank. But the Street Dawah Movement has claimed he fell into the orbit of the radical cleric Wissam Haddad. Haddad – who has ties to several convicted IS members, including Uweinat – has run his own street dawah project for several years. In a press release issued this week, Haddad did not address whether he knew the alleged shooter, but he said it was “misleading” to call Akram one of his followers because “no evidence has been produced showing any personal, organisation or instructional link” between the two. Haddad is not accused of being involved in the Bondi shootings.

In 2023, despite all of this, Sajid Akram was granted a gun licence. He ticked all the boxes; the registry was satisfied that he would use the weapons for hunting, and that he was a member of the Zastava Hunting Association, a gun club in Bonnyrigg. (A wallet that slipped out of Naveed’s pocket at Bondi suggests he was a member, too.) Akram would have had to give an address for a gun safe, that would have been inspected. It’s not clear where he kept his guns; many gun owners keep them at home. Serious questions remain about why a weapon was granted to someone living with a person who had been on an ASIO terrorism hot list.

Loading

Early the next year, in February, property records show an unusual transaction; one Akram sold the Bonnyrigg house to the other for about half the original purchase price. This is most often explained by a marital separation. It’s not known if the couple continued living under one roof, or if Sajid moved out – perhaps to the Campsie share house.

The Guardian interviewed former bricklaying colleagues of Naveed’s, saying he was known to be close to his father and that he had become closer to him, and his religion, as a result of his parents’ separation. Naveed’s colleagues had a different view of him from his school friends. “You spend a lot of time together, obviously, bricklaying – [which is a] pretty mind-numbing job, so you do a lot of talking,” one colleague told the publication, “but he was just a weird operator.”

Terrorism experts say the relationship between the two men may have fed their spiral. “It does almost certainly do things to the dynamics of radicalisation. If the two are on board, they are driving each other,” says the ANU’s West. The fact they had a legitimate reason for spending so much time together also gave them cover; it made their comings and goings harder for law enforcement to spot, and it reduced the likelihood of introducing people to the plot who were already being watched. “It’s not happening outside the house,” says West. “There are some operational security benefits [for the Akrams].”

Naveed’s mother says he was laid off from his bricklaying job a few months ago. His boss said he quit, citing a broken wrist from boxing, and asked for his entitlements to be paid.

At the beginning of November, father and son flew to the Philippines, which is no longer a hotbed of terrorism after a focused effort by government forces to crack down on it. Initial reports of the trip sparked suspicions the men had trained at a jihadist camp there, but staff at a hotel in the southern city of Davao – which the Daily Mail reports is in an area known for sex tourism – say they spent almost every day in their $24-a-day room, with its two single beds, and left every day for no more than two hours.

The hotel room in which Sajid and Naveed Akram stayed in Davao, Philippines; Passport photos of the alleged Bondi terrorists.

They registered with a Philippines telephone number and paid in cash. They extended their stay several times. They left wrappings from Jolibee, a fried-chicken fast food chain, in their room.

Jones says his contacts in the Philippines theorise that the men may have been visiting an unregistered madrassah, or Islamic religious school, for final spiritual preparation before the attack (fundamentalists believe dying in the cause of jihad will cleanse them of their sins and give them guaranteed entry to paradise). That might reveal a hint about whether the men were driven by Islamic ideology or Middle East politics. “If it does turn out to be [a madrassah], I would say this case is ideologically driven,” says Jones.

Loading

West wonders whether they went there hoping to find a training camp and realised they were not so easy to find or join – “you can’t just show up at a terrorist training camp and say ‘hey, we believe in what you do, can we hang out?’” – or whether they were paying for commercial, all-purpose military training, which is offered by army veterans to anyone willing to pay in parts of South-East Asia. “You can just pay a retired army guy who has a facility. He’ll teach you how to run around and wear an AK47,” West says.

Both West and Clarke say suggestions the men were skilled with weapons or in military tactics are overstated. The father was disarmed twice (for which two people paid with their lives, and one may lose an arm), and he wandered off the high ground. The son was better, but he lacked the signs of highly professional training, West says.

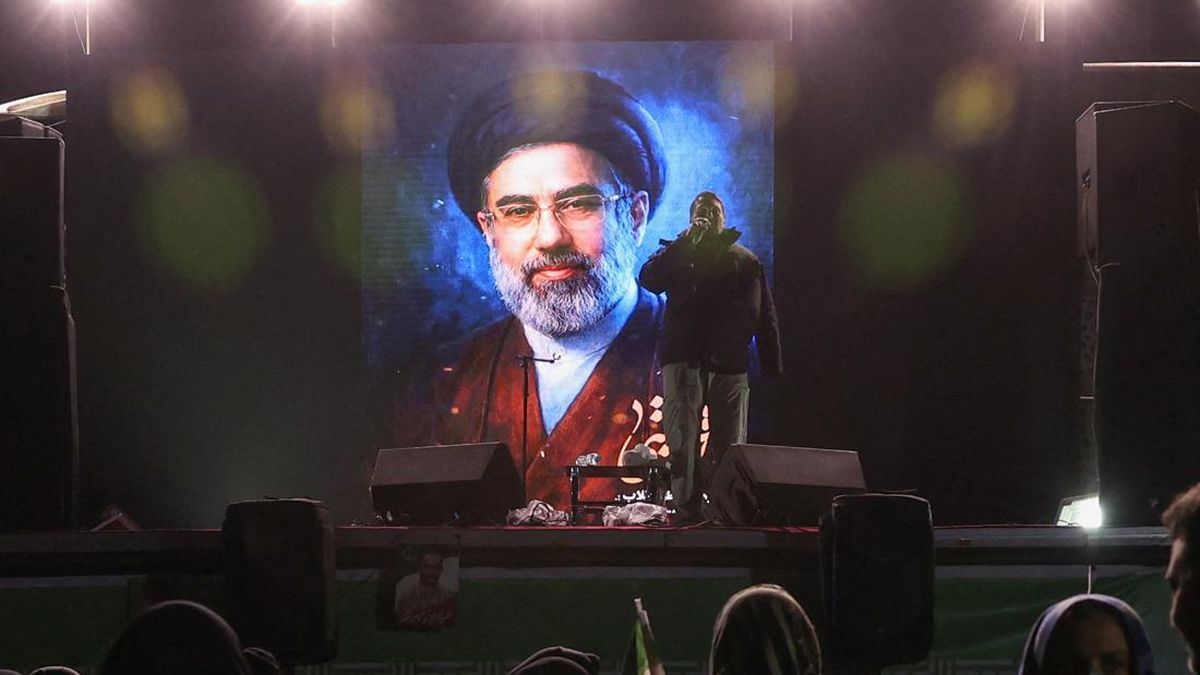

The interior of the rental in Campsie shared by the Akrams on their return from the Philippines.Credit: Nine

We know the two men returned from the Philippines in late November, and that their travel does not seem to have been flagged by border authorities. We know Naveed’s mother told reporters that her son had told her he was going to Jervis Bay on a fishing trip last weekend. We know he was at Campsie instead, and that shortly after 5pm on December 14, the two men drove to Bondi in a silver hatchback with their homemade Islamic state flags, improvised bombs, and six powerful weapons, and killed 15 people.

We know Sajid is dead, and Naveed is facing a slew of criminal charges.

We don’t know what prompted them to do it. We don’t know if the father radicalised the son, or the son the father, or if they fed each other’s delusions. We’re told they left a manifesto, which is highly unusual for ideological jihadis. We don’t know if they were adherents to purist Islamic State theology, or if they had been galvanised by Gaza. Hatred of Jews goes back more than a millennium, well before October 7. “You can remain consistent with your Islamic State ideology and come to the conclusion that targeting Jews at a Hanukkah celebration is the right thing to do,” says West. “Islamic state has targeted Jews and Jewish institutions repeatedly.”

What is certain is that there’s no simple answer. West is an expert on all types of radicalisation – far right, like Brenton Tarrant (who killed 51 people at New Zealand Islamic institutions), as well as jihadi extremists. He has broken down the process. It involves an interplay of three factors that feed one another differently in different people – cognitive processes, such as self-efficacy, morality, uncertainty and self-control; environmental factors, such as a sense of status difference, legitimacy, or identity in a group; and behavioural factors, which are influenced by the other two.

“In the real world, [it might mean] you’ve got a guy who is vulnerable to simple solutions to problems, and in trying to resolve that, he attaches himself to an identity like Nazism,” says West. “That reinforces the satisfaction, which reinforces self-identity, so now he doubles down, and tries to go [to catch-ups] as often as he can.”

Loading

These men might be, as West puts it, floating along in their ideological soup, and then there can be a catalyst; for Tarrant it was the death of a 12-year-old in a jihadist operation in Sweden. For the Akrams, the catalyst might have been the divorce, or the war in Gaza, or a fiery sermon by a malevolent self-styled preacher, or something no one knows about yet. “The underlying conditions are broad political grievances, dissatisfaction with the status quo, that makes you vulnerable when that catalyst event happens,” says West.

Most radicalised people never get to the point of murder. Lone wolves like the closeted Akrams are the hardest terrorists to detect. Hindsight is easy. Security agencies and governments will face tough questions about their decisions, and how they have allocated resources in a world in which the threats are splintering and multiplying – foreign interference, far-right extremists, jihadists – and whether they should have kept a better eye on this one.

None of it will be of any comfort to the families who lost people they loved in Bondi on Sunday night.

Start the day with a summary of the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up for our Morning Edition newsletter.