A former boarding house set to be developed into a single luxury home. An old-style block of 45 studios to be demolished and replaced by 25 luxury units. A massive new building of 250–300 apartments, with only 5 per cent allocated for affordable housing.

Locals in Kings Cross and Potts Point are alarmed by the erosion of cheaper housing in an area where battles for affordable homes started in the 1970s and led to the death of activist Juanita Nielsen.

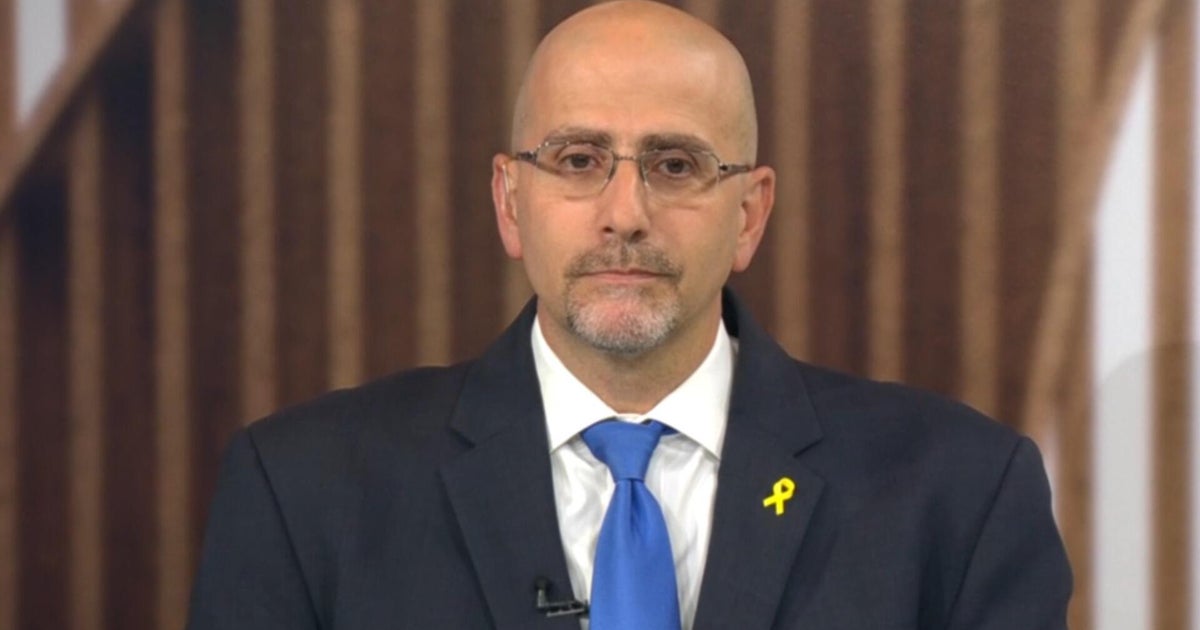

Artist Justine Muller (left) with local writer Elmo Keep and Sydney Deputy Lord Mayor Jess Miller. Credit: Edwina Pickles

“More and more affordable buildings in the area are being lost all the time to be converted to a smaller number of luxury homes,” said Kings Cross artist Justine Muller, 42, goddaughter of union giant Jack Mundey. His pioneering Green Bans protected huge swaths of the city through world-first strikes against working on projects that would have removed low-cost housing from areas like Woolloomooloo and The Rocks, and destroyed heritage.

“Creatives and artists are being pushed out. I rent in one of the last affordable blocks in Kings Cross and we live in fear that someone will come up and say they’re going to demolish it. There aren’t many options these days.”

The Kings Cross area has always been known for its diverse demographic, colourful history and numbers of creatives – artists, writers, performers – and that’s why many have chosen to live there, says writer Elmo Keep, 44.

Loading

“But it’s now in danger of becoming an enclave for extremely wealthy individuals who might be the only ones in the future who can afford to live here,” she said. “We all want more housing, but I can’t support it when it means moving people out of cheaper studios and one-bedroom units, out of the way, and out of the area.

“And even when we have a big new apartment development slated for the area, the developer is advertising just 5 per cent of it will be affordable housing, when it should be at least 15 per cent to rehouse some of those being forced out.”

A number of fights are under way over planned developments at a range of sites in the neighbourhood.

At 141, 141A and 143 Victoria Street, the founder of wealth management firm Fat Prophets, Angus Geddes, has been trying to develop three heritage terraces – a former registered boarding house, a backpackers’ hostel and a once-affordable housing site – into private residential dwellings. He’s seeking a review of the City of Sydney’s refusal of his plans.

“Everything is shot in those buildings, they’re past their use-by date and are on the cusp of falling down,” Geddes said. “I understand about the need for affordable housing, but the council can’t afford to maintain these houses; they can’t have their cake and eat it too. It requires a lot of money.

The former home of housing activist Juanita Nielsen in Victoria Street, Kings Cross.Credit: Edwina Pickles

“It’s important to preserve the fabric of the heritage architecture of the area and return the facades to how they looked 120 years ago and that’s what we’re trying to do.”

There’s a separate stoush going on at 117 Victoria Street, where developer Ceerose successfully appealed, at the NSW Land & Environment Court (LEC), a City of Sydney refusal to demolish an older-style affordable unit block of 45 units and in its place build 25 larger and more expensive dwellings. The council now has a policy of refusing any development that reduces the number of homes on a site by 15 per cent or more.

Ceerose assistant development manager Andrew Doueihi said the development would deliver seven brand-new affordable housing apartments out of the 25. “These will be targeted towards local key workers and managed by an independent housing provider,” he said. “The new contemporary homes will replace the existing building, which is no longer compliant with current building codes, and lacks contemporary fire safety and security amenities.”

Loading

Victoria Street is the same street where Juanita Nielsen campaigned against developers’ plans to demolish the historic terraces to make way for high-rise towers of luxury apartments.

Then there’s an application approved by the LEC for a low-cost 40-unit building at nearby 51-57 Bayswater Road to be replaced by one block of just 12 luxury three-bedroom apartments, as well as the long-running fight over The Chimes on Macleay Street with its 80 units, set to be replaced by 35. Another recent LEC decision allowed for a decrease to the number of apartments from 28 to 20 in buildings on a site at Billyard and Onslow avenues.

“There are certain developments where we can provide affordable housing options and other boutique ones where we can’t,” said Luke Berry, director of developer Third.i Group, which is working on the Bayswater Road project. “But also we need to unlock housing for people who want to sell [their apartments] and upsize or downsize and go into more suitable housing.”

Meanwhile, plans have been submitted for the heart of Kings Cross by fund manager Salter Brothers, redeveloping the Holiday Inn Potts Point, opposite Kings Cross railway station, into a new One Kings Cross precinct, including a 35- to 40-storey tower with 250 to 300 apartments – with 5 per cent for affordable housing.

A spokesman for Salter Brothers said: “The proposal submitted to the Housing Delivery Authority and selected to proceed under the HDA pathway has a mixture of public benefits – there is 5 per cent on-site key worker housing; over a third of the site dedicated to public spaces, laneways and connections; and Salter Brothers is funding all works associated with the new Kings Cross Station entry (to the west of Victoria Street) and concourse connection from Brougham Street.”

Newly elected City of Sydney Deputy Lord Mayor Jess Miller said the 5 per cent was the tiniest compensation for being allowed more space and height, and the contribution to affordable housing should be much closer to 15 per cent.

“With a state-significant development, affordable housing is also defined as 75 per cent below the market rate, which is a very wishy-washy figure, when we say it should be 30 per cent of someone’s income, and in perpetuity rather than five to 15 years,” Miller said.

“In practice, this isn’t policed either. It could be someone’s mates being put in there for a discount, as it’s not administered by an outside agency. I think if Juanita Nielsen was around now, she would be shocked and dismayed at the way this struggle for affordable housing has gone.”

Loading

Mark Skelsey, the author of a recent book about Nielsen, Views To Die For: Murder, Anarchy and the Battle for Sydney’s Future, said that it was clear that inner Sydney councils and the LEC were becoming increasingly active in their use of their powers to resist applications to replace low-cost existing housing with more expensive residences.

“But it is fitting that Victoria Street in Potts Point, where there were such ferocious battles 50 years ago about destruction of existing affordable housing, is now the centre of new conflict about the same issue,” he said.

Social planning expert Professor Roberta Ryan of the University of Newcastle, who lives in Kings Cross, said that much of the existing more affordable housing stock was built in the 1960s and is now rundown and unsuitable, with structural or fire safety issues.

“It’s pretty difficult for the private sector to provide any kind of necessary amenity at that price point,” she said. “And people deserve better than they have.

“So governments are investing unparalleled amounts of money in renewing existing social or affordable housing stock, and creating new opportunities on excess rail or road land, and often in partnership with community housing providers. That’s where the provision of low-cost housing should come from.”

Most Viewed in Property

Loading