When I interviewed Elizabeth Harrower for Spectrum in 2014, I was curious to know about her father. In her novels and short stories, fathers are often absent – killed offstage by illness or accident – or a malevolent presence. Children are orphaned, abandoned, mistreated and emotionally damaged. I wondered what had happened to her.

She told me she had been “a divorced child” and had not seen a happy marriage when she was young. But she shut down my question about her father: “We’ll leave my childhood where it belongs; many, many decades into the past.” As for her stepfather, not a word.

Harrower was 86 then and had every right to put the past behind her. But she was suddenly in the spotlight for the revival of books she had written as a young woman, and it was natural for journalists to ask about her family.

In the years after our interview I got to know her more, over afternoon tea at her apartment in Cremorne above Sydney Harbour. We talked about books and writers, especially her friends Patrick White, Christina Stead and Shirley Hazzard. We touched on family, both of us only children of divorced mothers, both enthusiastic about our Scottish roots, but there was no more about a father.

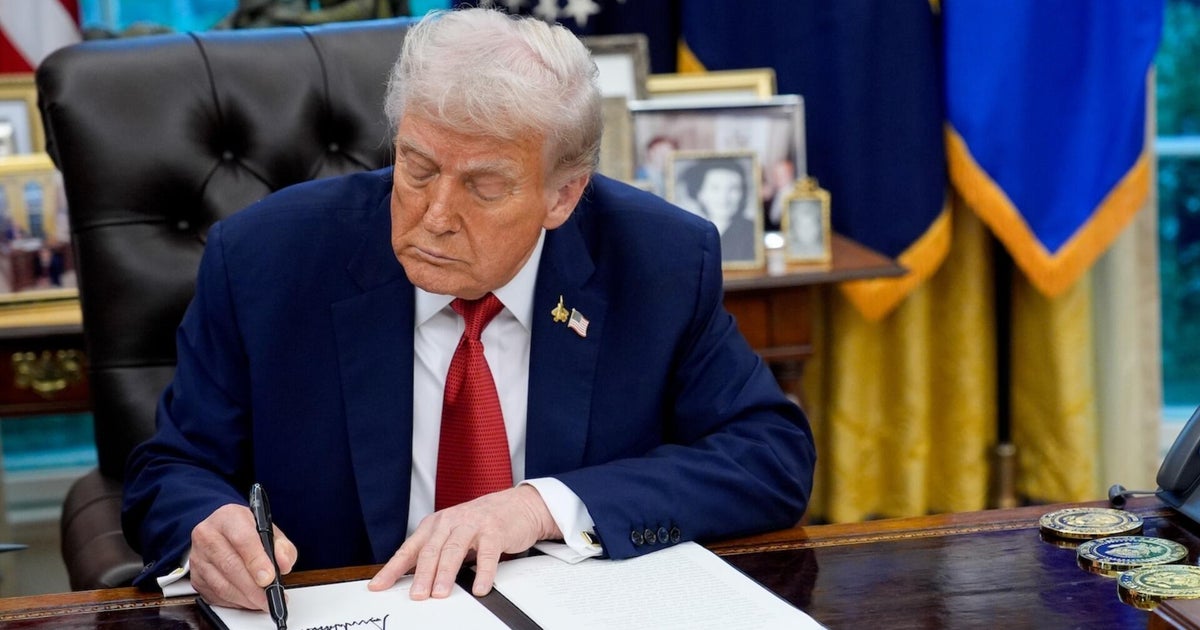

Elizabeth Harrower on the ship home to Sydney in 1959 after she had been living and writing in the UK for eight years.

Although I studied Australian literature at university, I had not read Harrower’s four novels from the 1950s and ’60s until they were reissued as Text Classics between 2012 and 2014. Michael Heyward at Text Publishing also persuaded her to allow publication of a fifth novel, In Certain Circles, which she had withdrawn from her British publisher in 1971, and a collection of short stories.

There was much fanfare for an author who had come out of obscurity to talk about books written half a century earlier. Critics from the Herald to the New Yorker marvelled at these rediscovered treasures.

Her novels are time capsules of life in Newcastle, Sydney and London in the years of Depression, war and post-war change. They ask eternal questions about how to live between good and evil, mind and body, love and freedom. I read them all then, and they took my breath away: Down in the City, The Long Prospect, The Catherine Wheel and The Watch Tower.

Here was an Australian writer informed by European literature and philosophy, with powers of ruthless observation and psychological insight into the aspirations and weaknesses of ordinary people. Young women struggle to be free of deadening suburban families and controlling men. Some succumb, while others escape through books, work and willpower.

When Harrower died in 2020, I felt lucky to have known this intelligent, curious woman in the years of her late renaissance, and intrigued by all I didn’t know. How did she become a writer, and why did she stop? Where had those intense novels come from? How did she create memorable characters such as The Watch Tower’s Felix Shaw, her most brilliant villain?

Journalist and author Susan Wyndham (right) with Elizabeth Harrower, celebrating her 91st birthday in 2019.

By then I was keen to write her biography and headed for the National Library of Australia in Canberra, where the personal papers she had deposited were at last open to the public. I had a tantalising glimpse before COVID shut me out.

Biography requires an addictive mixture of scholarly research, detective work and luck. It took years to piece together the story of Harrower’s life and family. There I found much of the material she used in her fiction, including the man who was the main model for the drunks and bullies, narcissists and cheats who drive her domestic dramas.

Betty Harrower, as her parents named her, was born in the industrial city of Newcastle in NSW in 1928. Her father, Frank, worked for the state railways and her mother, Margaret, refused to follow him to rural postings. After they divorced, Margaret moved to Sydney to train as a nurse and Betty stayed in Newcastle with her Scottish-born grandparents, until they divorced, too. At the age of 12, she joined her mother – and her new stepfather – in Manly on Sydney’s northern beaches.

No matter how carefully Harrower had buried her childhood, all this was laid out in divorce affidavits in the State Archives, and in newspaper reports that relished every accusation of adultery, desertion, drunkenness and violence. In an era before no-fault divorce, when most women were financially tied to their husbands, Betty’s broken family caused her pain and shame.

Later, I would interview Harrower’s surviving relatives, friends, editors, and hairdresser, and read her wide correspondence. During the pandemic, my best source was Trove, the digitised collection of newspapers and other printed material maintained by the National Library of Australia. One search led to another and mysteries were solved.

Author Elizabeth Harrower at her house in Cremorne in 2014.Credit: Lidia Nikonova

But how was I to find her stepfather? I didn’t even have a name. Then one day I came across a tiny item on the “Women’s Letters” page of the Bulletin, dated July 1, 1959: “Great preparations are in hand at the Mosman home of Mr and Mrs R.H. Kempley to welcome back her daughter, Elizabeth Harrower, and her friend Margaret Dick, who are arriving in the Southern Cross from England. Both girls are writers … ”

Harrower (no longer Betty) had spent eight years living in London in cold rented rooms, where she wrote her first three novels. With her Scottish cousin Margaret Dick, also a published novelist, she returned to Sydney to see her mother and was welcomed as an exciting new writer, often compared with Patrick White.

The name R.H. Kempley cracked open a history of criminal activity, and helped explain the never-married Harrower’s determination to remain free of any man who would try to dominate her.

English-born Richard Herbert Kempley had turned up in Sydney before World War I and trained in accountancy, a career that gave him a respectable veneer while he pursued a series of dodgy businesses. The tabloid Truth gleefully covered his trial in 1925 for stealing from a former employer to set up a phoney confectionery company. In court, he was described as “a crook, a thief and a cheap takedown”, “of shady character”, and a possible bigamist.

During the Depression Kempley was arrested in Newcastle for keeping illegal stills and running the largest ‘bootleg joint’ in Australia. By the time he was living in Sydney with Margaret Kempley (married or not), during World War II, he was selling black-market spirits to American servicemen in city hotels. Found guilty of conspiring to defeat national security regulations, he was sentenced to three years in prison.

Harrower loathed her stepfather, who was an unstable, bad-tempered alcoholic. He loved making money and he loved spending it on houses, cars, travel, and gifts for his wife. Her diamonds tagged her as his property.

Elizabeth Harrower in 1968, a couple of years after the publication of The Watch Tower.Credit:

In her fiction, Harrower would critically observe modern consumer society, and scrutinise coercive control and domestic abuse before feminism gave them those names. But in 1951, aged 23, she travelled with Margaret and Richard Kempley to the UK, and toured Europe for months in a Jaguar.

Frustratingly for a biographer, she threw away her diaries and letters to her mother from her eight years in London. “You have to protect people,” she said. Among her private papers a crucial diary from 1951 survives as a touching record of her transformation from nervous, homesick girl to forward-looking woman and writer.

She noted that her mother and stepfather, “Uncle Dick”, quarrelled on the ship – “he was in a bad way & wanted to argue about anything so he did. Then he marched off to have a drink. Mum nearly had a stroke.” Margaret made plans to leave the ship at Colombo with her daughter, but Kempley “reformed again” so they stayed.

On board, Harrower met Lady Bedingfeld, an English woman who told stories about her travel adventures, from seeing the Grand Prix and fashion shows in France, to deep-sea fishing in the West Indies. Harrower wrote in her diary on April 30: “Since I’ve met her I don’t feel a bit like going home after the holiday is over. I may stay in London & work there & travel round.”

Loading

In London, she was soon writing fiction. She described her first novel, Down in the City (published in 1957), as a little love letter to Sydney, with its vivid settings in the eastern suburbs. But attraction leads to a brutal marriage between Esther, the protected daughter of a wealthy Rose Bay family, and Stan, a rough Kings Cross businessman with a mistress, a drinking problem, and a resemblance to Kempley.

Back in Australia, Harrower wrote her fourth novel, The Watch Tower, a masterpiece of characterisation and stifling tension. She follows the divergent fates of two sisters, abandoned in wartime Sydney by their widowed mother.

Laura, the elder, is forced to work for Felix Shaw, the owner of a series of failing small businesses. He presses her into a pragmatic, loveless marriage so that bookish Clare can stay at school, but soon has both women slaving under his control at work and home in harbourside Neutral Bay.

Clearly Harrower saw her mother in Laura and herself in Clare as she wrote with cool fury at home in Neutral Bay and later Mosman, just blocks from the Kempleys’ house.

In 1966, Sydney Morning Herald critic Harry Kippax placed The Watch Tower alongside Patrick White’s The Solid Mandala as the year’s most distinguished novels. He praised Harrower for her talent in creating “a monster as continually credible, comic and nauseating as Felix Shaw”.

Felix admires Hitler and likens himself to Bluebeard, an evil figure of folklore who murdered his wives. (“He knew how to treat his women!” ) But Felix is a pathetic suburban tyrant, weeding his garden aggressively and laughing at his own jokes, an irrational drunk who takes out his insecurities on his wife. Harrower writes: “His misery was infectious … He merely walked slowly into the house with this dark, aggrieved and bitter air that inspired a dreadful awe and feeling of guilt in her … ‘Where’s the Herald?’ ”

Loading

Felix shares much of Kempley’s biography, from harsh naval training to accountancy exams, racing car accidents, purchase of a chocolate factory, black-market cronies and erratic property deals.

When asked if her novels were autobiographical, Harrower said they were pure fiction and once conceded that “the emotional truth” of her early life was there “but none of the facts”.

She was partly truthful. Her novels pluck a multitude of details from experience, observation, reading and imagination. They are heightened creations with elements of myth and satire, as she liked to say, “transmuted” from reality.

At the end of her life, however, she told one friend that The Watch Tower was autobiographical and another that Richard Kempley had been “poisonous” and “a monster”. For Harrower – and her readers – turning her wicked stepfather into a timeless character was an act of literary alchemy.

Susan Wyndham is a former Herald literary editor. Her biography Elizabeth Harrower: The Woman in the Watch Tower is published by NewSouth on October 1. The book’s launch, with Susan Wyndham in conversation with Bernadette Brennan, is at Gleebooks in Glebe on October 7 at 6pm.

The Booklist is a weekly newsletter for book lovers from Jason Steger. Get it delivered every Friday.