A single unsealed coal borehole in country Queensland is releasing the greenhouse gas equivalent of 10,000 cars each driving 12,000 kilometres a year – and it’s just one of 130,000 across the state.

The discovery was made during a University of Queensland study of a coal exploration borehole, which was still leaking methane decades after it had been dug.

Associate Professor Phil Hayes, along with colleague Dr Sebastian Hoerning, placed sensors at an undisclosed location on farmland in the Surat Basin in southern Queensland, in what they said was the first long-term measurement of methane emissions from an abandoned borehole.

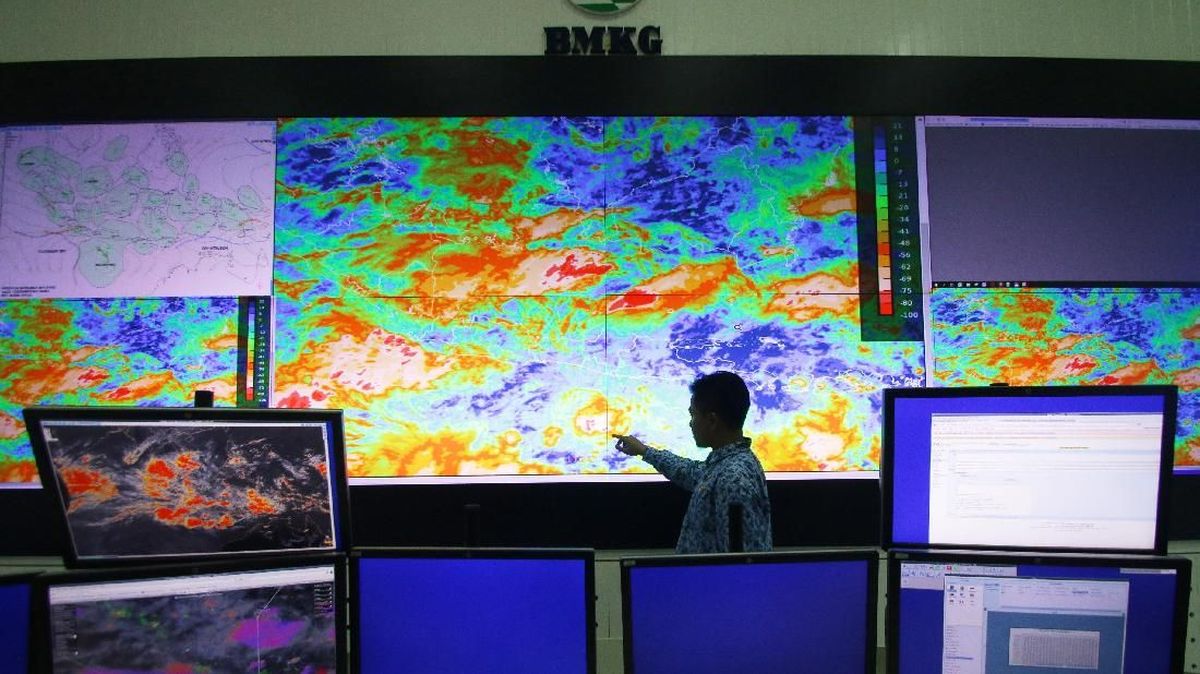

The Quantum Gas LiDAR system monitoring the coal exploration hole.Credit: UQ

They used a portable Quantum Gas LiDAR system, which can more accurately capture emissions that vary over time than common measurement methods, such as handheld sensors.

And the data they collected was stark – about 235 tonnes of the greenhouse gas was being emitted into the atmosphere each year, all from a single, small borehole.

Hayes said its climate impact was on par with 10,000 new cars, each driving 12,000 kilometres every year.

“We were pretty taken aback,” he said.

The researchers, from UQ’s Gas and Energy Transition Research Centre, have published their findings in the journal Science of the Total Environment.

Hayes said the coal hole they studied had been leaking for about 20 years and was just one of thousands across the state.

“There is an estimate of 130,000 coal exploration holes in Queensland, which is an enormous number,” he said.

Sensors picked up the methane escaping the coal hole in Queensland’s Surat Basin. Credit: UQ

“We’re nearly as certain as you can get a scientist to be that they’re not all leaking – some will have been sealed properly, some just won’t leak at all – but a small fraction are leaking somewhat substantially, from our survey.

“The one that the paper’s written about meets this threshold for a super emitter and possibly one of the other holes we’ve looked at would meet that as well.”

Hayes said the only hint of the emissions was a patch of dry dirt in the large paddock.

“It’s a patch that might be 10 by 10 metres in a paddock where nothing is growing. You can’t smell it – it’s just that visual impact,” he said.

“There’s so much methane in the soil that it’s suffocated the plants and nothing can grow there.”

When it came to combating climate change, Hayes said adequately sealing high-emission old boreholes was low-hanging fruit.

He said more surveys would likely reveal further opportunities for reducing Queensland’s greenhouse gas contributions by sealing old boreholes with the highest emissions.

“It’s probably a couple of hundred thousand dollars to get the equipment and to do it safely on site,” he said.

“You basically just need a long-arm excavator to pull back the soil and find the hole itself and, once you’ve found that, you run in some pipe and pumping a thick, heavy slurry, effectively, to kill the well and cement it up, meanwhile having to manage the gas on the surface.

“It’s not the sort of process that requires full-blown rocket science and big oil and gas technology, but it’s not without cost.”

Methane escaping from a since-sealed coal hole in Queensland’s Surat Basin.Credit: UQ

While their published paper focused on a single borehole, Hayes and Hoerning have also visited other sites, including where the leaking gas formed a water geyser.

“We were very much taken aback by that one as well,” he said.

“We surveyed that for probably only a couple of hours. We have actually been past that location since, and that hole has been plugged and abandoned by the Queensland government.

Loading

“So the government is partly on it, but partly not as well.”

Hayes said more needed to be done, starting with studying a larger sample of boreholes and ensuring leaks were adequately plugged.

“The only issue is, it’s not on anyone’s register, so no one can claim the benefit for fixing the problem,” he said.

“The landholder isn’t going to get some pat on the back and some financial recompense – it’s not their issue, it’s not their hole.

“The coal industry may be responsible – if the coal explorer still exists, they’re technically responsible, but there’s nothing in it for them, financially.”

Hayes said it may need to fall back to the state government to either compel companies, or plug the boreholes itself.

Get alerts on significant breaking news as happens. Sign up for our Breaking News Alert.

Most Viewed in National

Loading