Time flies. And waits for no one. And once lost, is never found. Yet still we try to keep time, and measure it. Let the French, Germans, and British fight over who invented the wearable clock, or watch, in the 1500s. This we know: it's the Swiss who refined the art, crafting the world's most intricate, and expensive, timepieces. This, though, is a curious interval for Swiss watches, those mechanical wonders, running not on batteries but on springs and gears. For one, you hardly need wrist candy to tell time; you can just consult your phone. And now Swiss watches are subject to the ups and downs of President Trump's tariffs. Yet these luxury items keep ticking, as we saw for ourselves in a place called Watch Valley.

Venture an hour north of Geneva, and wedged between ridges of the Jura mountains — baby cousins of the Alps — you'll enter the Vallée de Joux.

Don't be lulled by the green meadows and grazing cows. This is a global manufacturing hub — has been since the 17th-century, when local farmers needed a side-hustle during harsh winters, and started tinkering with big hands and little hands. Big name watch brands came of age here. As did solo master craftsmen, like Philippe Dufour.

Philippe Dufour: When I arrive the morning here, I light my pipe, take a coffee, put classic music, it's heaven.

In Dufour's one-room workshop, the old watchmaking methods endure. So do the tools and the tempo.

Jon Wertheim: Do you remember how long that took you – to make your first watch?

Philippe Dufour: Oh, yes. Took more than two years. Yes--

Jon Wertheim: One watch?

Philippe Dufour: Yeah. Yeah--

Jon Wertheim: How long does it take you to make a watch now?

Philippe Dufour: Well, it's about-- 2,000 hour, one year.

Philippe Dufour

60 Minutes

Philippe Dufour

60 Minutes

Dufour went to the local watchmaking school and worked for major brands before striking out on his own. Now 77, he's revered in the industry, meticulously crafting watches from start to finish. That third eye — a magnifying loupe, it's called — doesn't leave his head. Dufour prices his watches in the hundreds of thousands of dollars – custom-ordered and so in demand, when we asked to see a sample of his handiwork, he had none.

Well, except the one he was wearing.

Philippe Dufour: This is-- is a m-- is a model Simplicity. I launch it in-- year 2000. And this is the real first one. And I wear it every day since 2000.

Counter to its name, the Simplicity contains 153 individual components. Dufour hand finishes every part. Those broad stripes are his signature embellishment. Today, Swiss mechanical watches are like fine art pieces, appreciating assets that collectors can—and do—resell at auction.

Jon Wertheim: What do your watches sell for?

Philippe Dufour: Oof I mean, in t-- in term of-- auction one-- of the highest was 7 million.

Jon Wertheim: How do you process that?

Philippe Dufour: Well, I'm v-- I'm-- I'm very happy. I-- I d-- I don't get the money because it's not mine anymore, you know what I mean? But, I mean-- it's-- it's-- it's a recognition.

Just down the road, Antoine LeCoultre turned his family barn into a watchmaking studio. That was in 1833; now it houses the global brand Jaeger LeCoultre. The work is segmented, each employee tasked with one of 180 watchmaking crafts. Adjusting springs, sure, but also…

Jon Wertheim: Whoa…

…turning caterpillar secretions into glue for jewel bearings.

This artisan reproduces masterpiece paintings on the back of the watch with a one-thread brush.

The back of the watch is prime real-estate at Jaeger LeCoultre, best known for a model called the Reverso — originally made for polo players, who needed the watch to be protected during competition. Flip the face, and voilà.

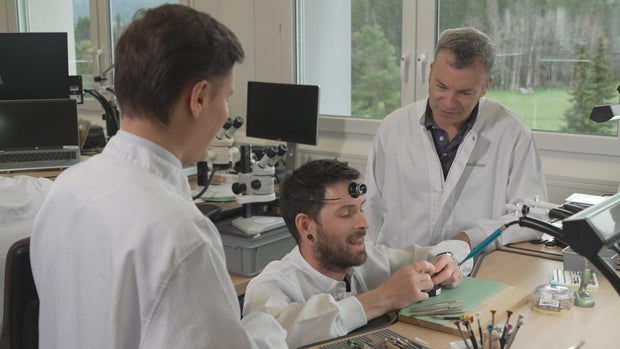

Jon Wertheim with Matthieu Sauret and a watchmaker at Jaeger LeCoultre

60 Minutes

Jon Wertheim with Matthieu Sauret and a watchmaker at Jaeger LeCoultre

60 Minutes

On our tour of the shop floor with brand director Matthieu Sauret, we watched a worker assemble his first Reverso; hundreds of hours go into perfecting this chime alone.

Jon Wertheim: --much nicer on the ears than Siri.

It's called a minute repeater. Leave it to the Swiss to pioneer what are known as complications, watch-speak for those additional mechanical flourishes beyond the basic display of time. Consider the perpetual calendar.

Matthieu Sauret: It tells you the day of the week, the date, the month, precise until 2,100.

Jon Wertheim: This is accounted for leap year you don't have to check this for the rest of the century.

Matthieu Sauret: No, you just have to wind it. The watch is a little computer. It knows everything.

Jon Wertheim: We joke about a computer but this is entirely mechanical.

Matthieu Sauret: Yes. There is no electronics at all in this timepiece. Everything is-- gears, gear trains, wheels, and springs.

Jon Wertheim: Watchmakers don't get nervous having an item in their hand worth a million and a half dollars that might take more than a year to put together?

Watchmaker: We are-- we are-- we are nervous.

Jon Wertheim: You look cool though. You pull it off.

Watchmaker: I look cool but I'm not.

On the other side of the Jura mountains, the goods come to market. Geneva: a cross between a city and a Swiss watch showroom. Rolex is the biggest player, more than a million units a year, roughly a third of the Swiss market share. Pharmaceuticals and banking are bigger sectors of the Swiss economy, but it's watchmaking that draws out the national character. Marc-André Deschoux is the founder of WatchesTV.

Marc-André Deschoux: In Switzerland we like to do things well.

Jon Wertheim: We hear about that famous Swiss precision.

Marc-André Deschoux: It's all about very minute details.

Jon Wertheim: This is not a product that degrades over time.

Jon Wertheim and Marc-André Deschoux

60 Minutes

Jon Wertheim and Marc-André Deschoux

60 Minutes

Marc-André Deschoux: Not really. A watch movement is something that is absolutely incredible if you think about it. It runs 24 hour a day, OK? And some people are saying, like min –minus plus of five seconds per-- per day. Oh, that's-- that's a big thing." But if you think about it, in the day, I mean, you have 86,400 seconds, OK? So if it-- you have a little bit distortion of-- five seconds, that's less than 0.01%. I mean, it's nothing.

If the Swiss can get a little precious about their precision, it's a function of history. In the 70s and 80s, Swiss watchmaking was decimated by the so-called quartz crisis, when Japan in particular began pedaling more accurate watches — for a fraction of the price — run on a quartz crystal and a battery. The Swiss response?

They launched the quartz-powered Swatch watch, plastic and chic, but then doubled down on the high-end mechanical market, adopting Alpine-high pricing and limited supply as business model.

Léo Rodriguez: It's only 1.75 millimeter thick.

At Richard Mille, we tried on this $2 million mechanical watch. A mind-bending price tag. But it does explain how Swiss watches account for fewer than 2% of the units sold globally but more than 50% of the market's overall value.

Of course, it's a small cohort that can afford this kind of status symbol, the equivalent of a Ferrari for the wrist. And it's gauche to walk into a shop and just buy a watch. It's a process. A dance, done in gloves. At Patek Phillipe, we were shown a new model with a split-seconds chronograph.

Nicolas Clemens: Let me put it on your wrist.

Marc-André Deschoux: This is gonna be nice.

List price: north of $300,000.

Jon Wertheim: If somebody said, " I love this watch. I saw this in your window," can they walk in off the street and say, "Please-- please take my credit card?"

Nicolas Clemens: Uh, thats -that's a difficult one but, um, sometimes a bit of patience is necessary.

Said patience can be measured in years. Some waitlists can run a decade.

Jon Wertheim: Help us make sense of the wait lists and the-- the supply and demand.

Marc-André Deschoux: It's a way of driving this desirability-- for a product, you know, so that you can't just-- it's not a question of money. You-- you really need to, you know, go along this kind of journey to-- to-- to get your watch.

The journey has been bumpy of late. Earlier this year, the U.S. issued tariffs on Swiss exports at a punishing 39%, driving prices even higher. But tariffs are flexible in a way time is not. After captains of Swiss industry — including watch company executives — visited the Oval Office last month, the Trump administration dropped the Swiss tariff rate to 15%. (And yes, that gold-plated desk clock was a gift from the CEO of Rolex.)

Plugging away through all this back and forth: Max Büsser, founder of niche brand MB&F. An engineer by training, he started the company in 2005 and struggled at first.

Jon Wertheim and Max Büsser, founder of watch brand MB&F

60 Minutes

Jon Wertheim and Max Büsser, founder of watch brand MB&F

60 Minutes

Max Büsser: And then 2020, COVID happened. We had hundreds, thousands of people contacting us saying, "How can I get one of your watches?"

Jon Wertheim: Could you accommodate this demand?

Max Büsser: No, because we don't wanna grow.

That's right: Büsser has no interest in ramping up from his current output of roughly 400 watches a year.

Max Büsser: See the level of detailing…

Jon Wertheim: Oh wow.

Max Büsser: You're looking as if you're looking at a little city. And of course all of this is not only beautiful, it has to function.

The loupe lays bare just how painstaking this work can be.

Jon Wertheim: I mean, this is a - - these are poppy seeds that's a screw that's smaller… that's a grain of sand right there.

Max Büsser: This is the level…

Jon Wertheim: … this is the craftsmanship here…

Max Büsser: …of craftsmanship competence of these people.

Max Büsser: I believe watchmaking is art. Everybody says "The art of watchmaking." So if watchmaking is art, why are 99% of watches look the same?

Büsser does not stand accused of conformity. He used a bulldog as inspiration for this model and told us telling time is not the point.

Max Büsser: We all know that what we do is totally pointless.

Jon Wertheim: What do you mean--

Max Büsser: I mean, a mechanical watch is totally pointless today. It was pointless in 1972 when the Quartz era arrived and so anybody who tries to tell you, "Yes, a mechanical watch has a point," except for emotional art and artisanship, I don't think so.

Büsser's company has grown to the point he recently sold a 25% share to the Chanel brand. But it's small enough, he still interviews clients before selling them a watch, which can easily run $250,000.

Jon Wertheim: How-- how do you, as an artist, feel about this when some of your customers are now v-- viewing this not as a piece of art, as a functional timepiece, but as an investment?

Max Büsser: It really, really annoys me. It's the worst reason to buy a beautiful piece of watchmaking. Now, don't get me wrong. I'm very happy if our customers can not lose money, or even make money reselling one of our watches. It's-- it's a beautiful gift for both of us. But it shouldn't be the reason.

You will not be surprised to learn where Büsser found the template for his life's work.

Max Büsser: Philippe is a legend he went solo when nobody was solo.

Back in the Vallée de Joux, the O.G., Philippe Dufour, has taken on a new apprentice, Danièla, who also happens to be his 24-year-old daughter.

Master watchmaker Philippe Dufour and Danièla Dufour, his daughter and apprentice

60 Minutes

Master watchmaker Philippe Dufour and Danièla Dufour, his daughter and apprentice

60 Minutes

Danièla Dufour: I really have a kind of deep relationship with my father, and so I was super curious about all the time he was spending in the workshop. You see the magic operating. He's-- in the front of his bench working on something that you cannot even see without the loupe, and-- you just listen, a little "I made it."

Jon Wertheim: Sigh of relief.

Danièla Dufour: Yes. And then you see the-- the heart of-- of the-- the watch beating for the first time and you understand that he just created life, and you want to do the same thing.

Before we left the workshop, the Dufours insisted on showing us this party trick: a half-dozen of his pocket watches set to chime in synchronicity, meant to echo the sounds of the valley.

Philippe Dufour: When the farmer is going up on the mountains you know, with the big bell.

Jon Wertheim: All these years, and it still brings you pleasure and a smile--

Philippe Dufour: Yeah. Yeah. Marvelous.

Jon Wertheim: Marvelous.

Philippe Dufour: Yeah.

It brought us a smile, too. But, then again, we're suckers for the evocative sound of a classic, mechanical timepiece.

Produced by Nathalie Sommer. Associate producer, Kaylee Tully. Broadcast associate, Kaylee Tully. Edited by Matthew Lev.