Shefali Batta felt the blade before she saw it.

She stood paralysed. She thought she was going to die. From the phone in her hand, she heard a shopping centre security guard say “hello”. Silent, she was realising her deepest fear – a scene of horror that had been building since she had witnessed two men slash and stab each other in her grocery store two years earlier.

Moments before, she had watched the tension unfold from behind her desk as a slight, drug-affected woman with a bag overflowing with groceries at her side put up her hands to ward off the security guard. “You need to show me your bag, and then I will let you leave,” he repeated in a calm, measured tone.

Fearing the worst, Batta stepped outside the service desk to call for back-up.

She was standing behind the security guard when the woman attacked him, then turned on her. She felt the blade slide across her stomach, but it didn’t cut. It was a moment of instinct that forced her to leave retail for good.

Victorian retail workers are facing a crisis of abuse, violence, theft and knife crime that could leave countless staff traumatised, in a workforce of which a third are under 24 years old.

One day into the ban, and inches from death

The Allan government hopes that machete bans and new laws to penalise criminals who assault retail workers are the answer. But not everyone is convinced.

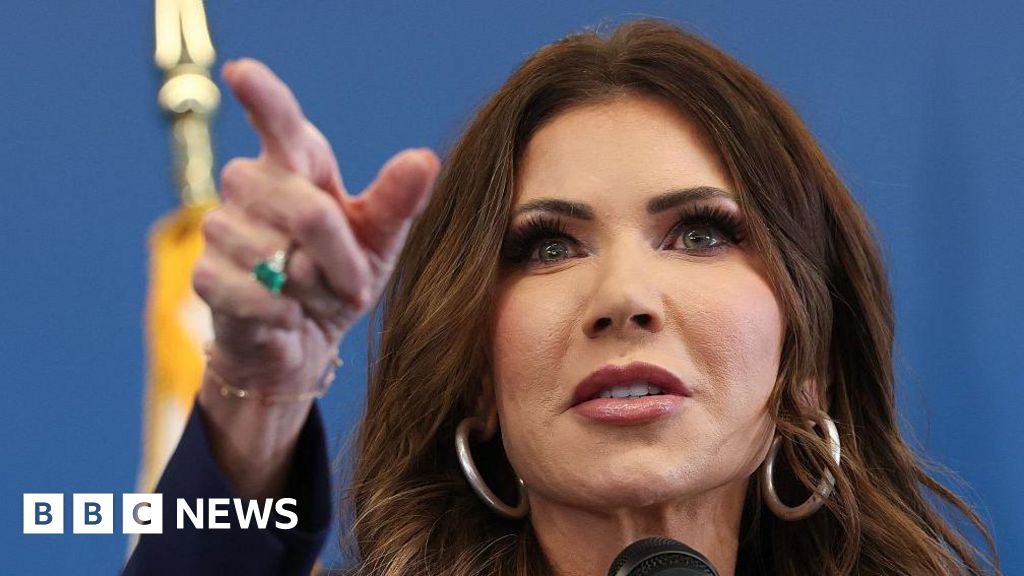

Premier Jacinta Allan posed with the state’s policing minister and assistant commissioner beside a machete amnesty bin – one of 45 to be set up outside police stations across the state.

A member of the public walking past Melbourne’s police headquarters on July 31 stopped to congratulate Allan on her work, and – within a few minutes of talking – the premier, grinning, wrapped the man in a hug.

Victorian Premier Jacinta Allan, Police Minister Anthony Carbines and Assistant Police Commissioner Brett Curran launching machete amnesty bins in July.Credit: Jason South

The launch came about two months after the wild Northland Shopping Centre machete brawl in Melbourne’s north, where shoppers were sent running, screaming and hiding in stores as rival gangs went head-to-head.

The scenes prompted the Victorian government to bring forward a ban on the sale of machetes to May 28, but between it coming into effect and Allan launching the amnesty bins, The Age counted at least a dozen significant incidents involving knives or machetes at stores across the state.

Premier Jacinta Allan hugs a passer-by at the launch of the machete amnesty bins.Credit: Jason South

The night after the ban kicked in, a Woolworths worker in East Gippsland was on his break when an erratic woman walked up to him and stabbed him in the stomach with a utility knife.

By midnight, he was lying on a hospital bed in The Alfred.

“It probably scared the f--- out of everyone, to be honest,” said the Woolworths worker, who asked not to be named to protect his privacy.

“I ended up with a 1.5-centimetre laceration into the liver – which required two different surgeries – and a bile leak.

“[The stab wound] was pretty close to the main vein that goes into the liver … and if she had got to that, I would not be here. It leads to massive blood loss pretty damn quick.”

About a week after that attack, a security guard at Dan Murphy’s in Fawkner in Melbourne’s north attempted to stop an offender stealing bottles of alcohol. CCTV captured staff and customers’ shock when he pulled out a machete almost the length of his arm, waving it at them.

A very Victorian crisis

Victoria’s Australia-first machete ban intensified on September 1, making it illegal to carry or own one of the weapons in the state without an exemption.

Flouting the rules now carries up to two years’ jail, but, as with the prohibition on sales, experts warn it will do little to stop violence in stores.

Brianna Chesser, associate professor in criminology and justice at RMIT University, said almost every major metropolitan Melbourne shopping centre has had a machete slashing in the past six months.

Organised crime had surged in Victorian retail settings since early 2024 as gangs swarmed shopping centres, Chesser said. The increase in retail crime comes alongside a rise in thefts across the state.

“Post-COVID, there are a lot of young people that became school refusers, who are not in meaningful or pro-social activities any more and get involved in these organised crime gangs,” said Chesser, also the principal lawyer of Melbourne firm Chesser Lawyers.

“There are just a whole lot of young people with not much else to do.”

RMIT University associate criminology and justice professor Brianna Chesser.Credit: Justin McManus

There was an 18 per cent rise in offences committed by 10- to 17-year-olds in the 12 months to March this year in Victoria, according to the Crime Statistics Agency. Youth offending in Victoria is at its highest level since electronic records began in 1993.

Chesser predicted Victoria’s machete amnesty would have much the same effect as Australia’s 1996 gun amnesty – law-abiding citizens handing the weapons in, but people who own them for nefarious reasons maintaining their grip.

Almost 1400 machetes had been disposed of in the state’s 45 amnesty bins as of September 12, according to the state government.

The Allan government’s ban on the sale of machetes – which resulted in thousands being stripped from shelves – would make the weapons harder to acquire, “but it certainly won’t be impossible”, Chesser said.

“It will just become like the acquisition of any other weapon in Victoria – impossible for regular citizens, but just slightly more difficult for those people who are looking to commit crimes,” she said.

Loading

Thefts in Victoria rose by almost 30 per cent in 2024 – the steepest rise of any Australian state or territory, according to recent data published by the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

About a third of thefts in Victoria happened in retail settings (not including car thefts), affecting about 55,000 victims.

Nationally, Coles’ Victorian stores are the worst affected by retail crime, a spokesman said. Despite having more stores in NSW, Coles’ Victorian supermarkets are experiencing 40 per cent more retail crime incidents.

Of all the security guards Coles employs in Australia, more than half of their hours are worked in Victoria.

Woolworths has reported a 26 per cent increase in violent incidents, and attributes half of that surge to its 280 Victorian stores.

Coles and Woolworths have recently deployed body-worn cameras to deter violence and protect workers.

Ritchies IGA chief executive Fred Harrison has publicly considered closing stores in Victoria as retail crime in the state reaches “crisis point”. Of Ritchies IGA’s 85 Australian stores, 52 are in Victoria. “I’d say 95 per cent of the issues that we are having today as a business are all in Victoria,” Harrison recently told the ABC’s 7.30.

Victoria Police warns retail thefts are consistently underreported, and its intelligence suggests that as many as half of shoplifters are first-time offenders.

“Sustained cost-of-living pressures have driven retail theft to record highs,” said Commander Karen Nyholm, who is responsible for the force’s retail theft portfolio.

“Many people have turned to shop stealing for the first time, while organised criminals are also on-selling stolen goods, such as groceries and alcohol, as costs soar.”

Loading

The Allan government has vowed to introduce laws by the end of this year to punish criminals who assault retail workers. It has said strengthened bail laws – which came into effect in March – are putting more people behind bars on remand.

Police were also granted expanded powers in March, allowing them to stop and search anyone in “designated areas”.

A Victorian government spokeswoman said: “We will introduce tougher laws this year to protect retail workers from crime – and we’ll continue to look at new measures to stamp it out.”

‘Focusing on a particular item makes people feel good – it’s very politically easy to do – but it doesn’t actually achieve genuine public safety improvements.’

Samara McPhedran, Griffith University researcherSamara McPhedran, principal research fellow of Griffith University’s violence research and prevention program, said crime statistics were “really, really rubbery”, as they failed to consider population increases, along with concerted police campaigns to detect more weapons and crime.

“The more you go looking for things, the more you tend to find them,” she said.

That doesn’t mean that crime statistics are wrong. However, McPhedran urged the importance of being aware that politicians use fear of violence as a means of “political currency”, and make the public hyperaware of it as a tactic.

“That’s why we see entire election campaigns based around law and order,” she said.

Generally, violence has decreased over the decades.

“So even though we have less violence, we have a lot more attention given to what does occur, and a great deal of fearmongering around that, and political point scoring,” McPhedran said.

She said that based on evidence, it was unrealistic to expect the machete ban – and other measures like it – would address the issue of violence.

“Focusing on a particular item makes people feel good – it’s very politically easy to do, it gets headlines – but it doesn’t actually achieve genuine public safety improvements,” she said.

“We need to be looking at those social, economic and environmental circumstances that lead people to engage in violence because until and unless we do that, these incidents are just going to keep occurring.”

Shopping centres ‘living in the old days’

It became common knowledge during the COVID-19 pandemic retail workers were dealing with rising levels of violence and abuse.

Loading

Since then, Victoria has “sadly reached a new plateau”, according to retail union secretary Michael Donovan.

“Our members are telling us loud and clear: customer abuse, theft and violence are getting worse,” said Donovan, who heads the Victorian Shop, Distributive and Allied Employees Association.

“In some instances, people are not directly attacked because there might be two gangs fighting each other. However, this is a very frightening experience for our members because they don’t know whether it’s a serious attack on them and customers.

“The current period is the worst period we’ve seen on knife crimes. It’s very disturbing.”

Young people between the ages of 15 and 24 account for up to 35 per cent of all retail workers – more than double their representation in other Australian industries, according to the Fair Work Commission.

The union was hearing from many retail employees who said they felt unsafe going to work, Donovan said.

Statistics show the fear is justified. Weapons offences in retail settings in Victoria have more than doubled in less than a decade, with 1252 recorded in 2025, according to the Crime Statistics Agency.

“Parents are rightly concerned when their kids are exposed to abuse, threats or violence in what should be safe and low-risk workplaces,” Donovan said.

Shefali Batta began working in childcare after leaving retail. Credit: Wayne Taylor

The union wants more severe penalties for people who abuse retail workers to come into effect this year.

It also wants the Victorian government to roll out workplace protection orders – “a bit like apprehended violence orders” – and force retailers to lock up knives and other bladed items until they are sold.

“They can secure cigarettes, they can secure expensive alcohol, they can secure expensive perfume,” Donovan said. “They should be able to secure weapons that can be used against retail workers and customers.”

‘The current period is the worst period we’ve seen on knife crimes. It’s very disturbing.’

Michael Donovan, SDA Victoria secretaryShopping centres in Victoria were “living in the old days”, when the only security incidents they had to deal with were lone actors causing trouble rather than handling incidents involving criminal gangs, he said.

It meant guards were only able to conduct surveillance and then call the police, rather than deal directly with a major security situation, he said.

Loading

Police Association Victoria secretary Wayne Gatt said incidents like those at Northland and Bondi in Sydney, where Joel Cauchi killed six people before being shot dead by police, showed knives “destroy lives”.

“[The machete ban] strengthens legislation … to be effective, though, new laws must be coupled with tough sentences at court,” Gatt said.

The retail union wants increased police presence in and around shopping centres.

This makes sense to Batta. She wasn’t stabbed two years ago when she stepped out from behind the service desk. But she will never work in retail again.

Now that she works in childcare, there are moments when she misses her old job.

“I used to feel so happy working there because I’m a very bubbly person, I love talking to people, I love interacting,” Batta said. “But now, after that, I just stopped.”

Start the day with a summary of the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up for our Morning Edition newsletter.