By Cameron Woodhead

October 5, 2025 — 1.47pm

THEATRE

Rebecca ★★★★

Melbourne Theatre Company, Sumner Theatre, until November 5

Rebecca is the second Gothic fiction from Daphne du Maurier to be adapted for Melbourne’s main stage this year, after The Birds at the Malthouse in May. Both were popular bestsellers made into Hitchcock films, so it’s fair to ask: what can theatre bring to their retelling that film can’t?

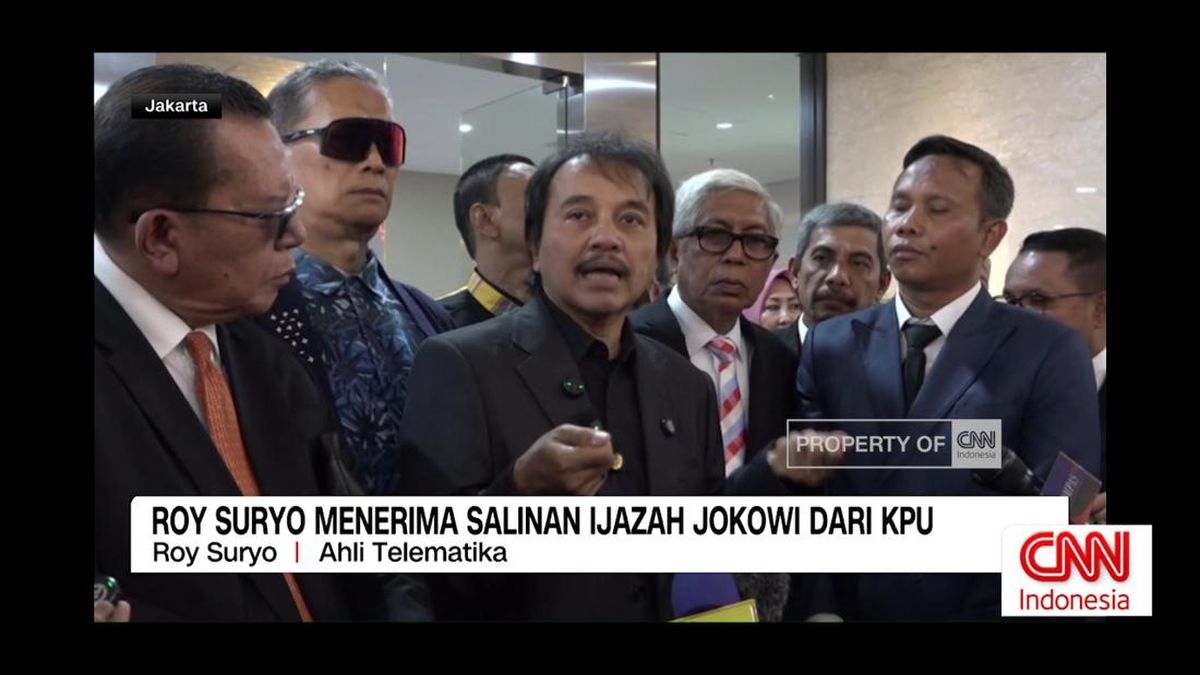

Nikki Shiels in a scene from RebeccaCredit: Pia Johnson

In Matthew Lutton’s no-frills adaptation of The Birds, the intimacy of sound predominated. Paula Arundell’s almost conspiratorial storytelling coaxed audiences into the claustrophobic monodrama; audio tech immersed us in the horror of unexplained avian attacks individually, creating a private, and deeply unnerving, soundscape for each spectator.

Anne-Louise Sarks’ Rebecca has frills. This is commercial theatre with elegant production values, poised and atmospheric design, a formidable cast, and a script that allows the seeds of this iconic romantic thriller to bloom into morbid flower.

An unnamed young woman (Nikki Shiels) meets grieving aristocrat Maxim de Winter (Stephen Phillips) by chance in Monte Carlo. A whirlwind romance leads to marriage, and she moves with him to Manderley – a stately manor home by the sea in Cornwall – where she quickly falls under the shadow of Maxim’s recently deceased first wife, Rebecca.

As the severe housekeeper Mrs Danvers (Pamela Rabe) begins to manipulate the new lady of the house, Maxim becomes remote and emotionally withdrawn. All roads point to Rebecca as the cause. Is Maxim still in love with her? How could anyone ever live up to Rebecca’s reputation for feminine perfection? And how, exactly, did Rebecca die?

Scandalous revelations and sudden twists await as she probes the secrets her haunted husband is hiding from her.

Pamela Rabe as Mrs Danvers is ideal casting.Credit: Pia Johnson

Design elements fuse into a triumph of Gothic sensibility: the brooding insistence of the sound design (Grace Ferguson and Joe Paradise Lui); Paul Jackson’s nimbus-smeared lighting; Marg Horwell’s astute eye for period fashion and the visual precision behind each scene change, every mist and mirror.

Shiels inhabits the insecurities of the heroine, her vulnerability, and her descent into domestic horror with compelling presence. There’s a jolting character transformation that might be more credible had it been achieved in a more graduated way, but the romance opposite Phillips holds your attention, and I particularly enjoyed Shiels going toe-to-toe with Pamela Rabe.

Long before her award-winning role in Wentworth, I’ve wanted to see Rabe as Mrs Danvers. It’s ideal casting, and Rabe’s husky apparition turns into a creature of flesh and blood as it builds a sapphic subtext (disallowed by censors in the Hitchcock movie) to the character’s deranged obsession. The fetishisation of the feminine, and the power-play between the two women, has a transfixing, performative quality that reminded me a little of the murderous sisters in Jean Genet’s The Maids.

Loading

And it’s Mrs Danvers, interestingly, who gives the staunchest rallying cry regarding social freedom for women.

Sarks appears to deny no perspective on the sources of psychological horror in Rebecca, tantalising us with possibilities. It’s thought-provoking, even if they don’t all coalesce into effective drama.

Newcomers to Rebecca might strain, too, to make sense of plot twists hastily telegraphed toward the end. It’s a bumpy climax after such a smooth ride to get there, though a small flaw in an otherwise slick, solidly crafted entertainment.

Reviewed by Cameron Woodhead

The Booklist is a weekly newsletter for book lovers from Jason Steger. Get it delivered every Friday.

Most Viewed in Culture

Loading