High-priced housing and the struggle to afford everyday necessities are killing the desire of Australian couples to have children as signs grow that traditional attitudes towards everything from marriage to the role of women in the workforce are rapidly breaking down.

A long-running survey of the Australian public’s values found the number of women who never want to have children has almost doubled over the past two decades, with both sexes in their prime child-rearing ages shunning the idea of starting families.

And in a clear threat to conservative political parties, the same survey shows a collapse in support for traditional values across all generations, with sentiment improving significantly towards single parenting, homosexual relationships and the participation of mothers in the workforce.

The Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey (HILDA) has tracked the same 16,000 people for more than two decades, delivering one of the world’s most respected long-term social surveys.

In 2005, 8 per cent of women and 11 per cent of men did not want children. That has climbed to 14 per cent and 15 per cent respectively. More than a quarter of both sexes either don’t want a baby or just a single child, almost matching the proportion who want three or more.

For the first time since the survey started, the desired number of children by either sex across all age groups has fallen below 2.1, which is the natural replacement level for a population.

Among women aged 18 to 49, almost 85 per cent said that cost was an important or very important factor holding them back from having a child.

While more than 70 per cent said having someone to love was important in deciding to have a child, other economic factors such as the security of a partner’s job (78 per cent), the availability and affordability of childcare (75 per cent) and being able to buy a home (67 per cent) were also vital.

Hannah Kaine, a 25-year-old lawyer from Sydney, said cost was a key reason she and her fiance were not planning to have children. She also listed as factors global instabilities, the impact on her career as a lawyer and the loss of freedom and flexibility.

“I just can’t justify putting that extra pressure on my career and on my time. I think it would mean sacrificing a lot of the things that I enjoy doing ... it feels difficult to put more stress on our lives, and also generally, on the resources of the world by bringing an extra child into the world,” she said.

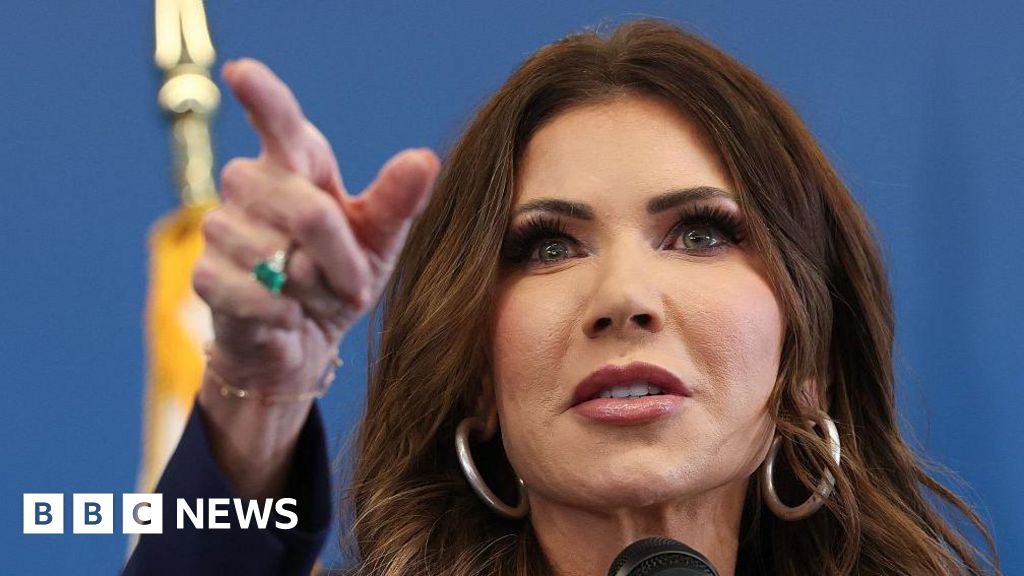

Hannah Kaine will be getting married in April but has decided not to have children.Credit: Louie Douvis

There were 286,998 births across the country in 2023, the most recently available figures. It was the lowest number of registered births since 2007, when 292,152 people were born in Australia.

Report lead author Inga Lass of the Melbourne Institute said the cost of housing was putting off couples from having children.

She said parents looking for a good public school were often paying an additional premium to secure a home in the right school zone, while the high cost of child care was another factor.

Lass noted the pressure on parents to do the best possible job had led to the phenomenon of “intensive parenting”.

“This means that parents are expected to invest a very significant amount of their time, energy and money into the development of their children and prioritise their children’s needs over their own,” she said.

“Such a high bar is difficult to meet, especially with more than one or two children, and might also deter people from deciding to have children in the first place.”

Tied to the drop in the desire for children is a collapse in what had long been considered traditional values.

Loading

In 2005, 52 per cent of women and 57 per cent of men agreed that marriage was a lifetime relationship and should never be ended. That has fallen to 30 per cent among women and 41 per cent among men.

Last year, 120,844 couples were married, taking the crude marriage rate – the number of marriages per 1000 people – down to 5.5. There are fewer marriages taking place now than in the mid-2010s.

Kaine, who is set to marry her fiance in April after seven years together, said the couple had only decided to wed after they had purchased a property and settled into their careers.

She said they probably would have delayed getting married if they lacked financial stability, and she didn’t see the institution of marriage as sacrosanct.

Loading

“I see my commitment to my partner as a lifetime commitment ... I can’t imagine that anything would change that. But I don’t think, if things were to go wrong down the track, I would let the fact that I’m married get in the way of me taking any action,” she said.

About two-fifths of women believe children usually grow up happier if they have a home with a mother and father. In 2005, two-thirds of women held that view.

More than 70 per cent of men agree it’s okay to end a marriage even if children are involved, compared to 62 per cent in 2005.

The proportion of both sexes who believe it’s all right for a woman to have a child as a single parent has climbed from around one-third to 54 per cent among men and 68 per cent among women.

At the turn of the century, almost 40 per cent of both sexes agreed that mothers who don’t need the money should not be in the paid workforce. This has dropped to 17 per cent support among men and just 13 per cent among women.

Both sexes are much more accepting of homosexual relationships. In 2005, 44 per cent of women and 32 per cent of men said homosexual couples should have the same rights as heterosexual couples. Among women the rate of support is 74 per cent, while among men it is 63 per cent.

Cut through the noise of federal politics with news, views and expert analysis. Subscribers can sign up to our weekly Inside Politics newsletter.

Most Viewed in Politics

Loading