The operator of Melbourne’s only safe injection room has admitted the service initially failed to adequately address community safety concerns about anti-social behaviour of drug-users.

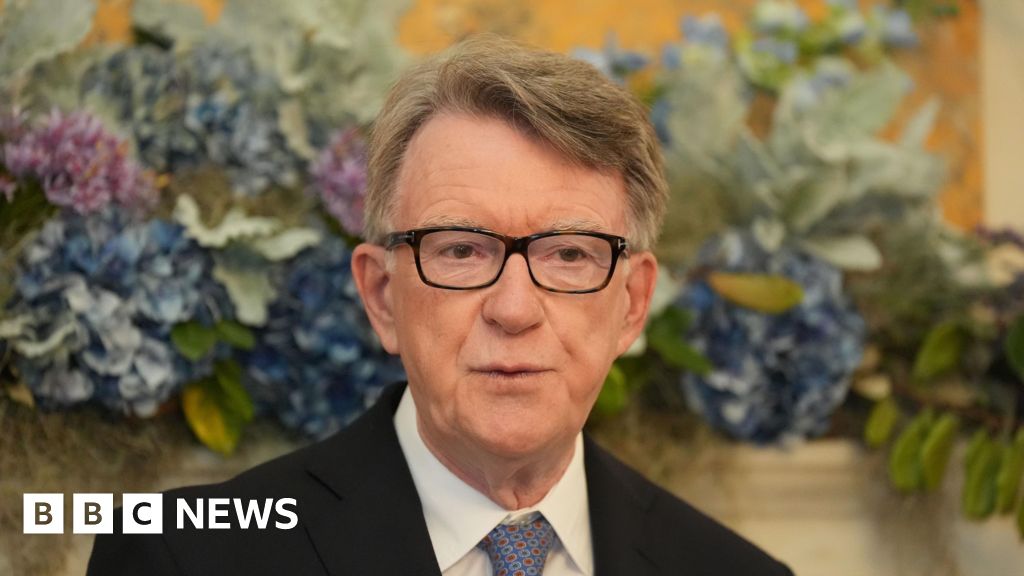

In her first media interview since taking over two years ago, North Richmond Community Health chief executive Simone Heald said her team was now focused on mending trust with locals. A $1.7 million landscaping project of the injecting room grounds has recently been completed to improve the look and feel of the area.

Simone Heald, chief executive of North Richmond Community Health and the Safe Injecting Room service.Credit: Paul Jeffers

Despite this, drug reform advocates and the Yarra Council warn the service will continue to be hampered by an unsustainable and unfair burden after Premier Jacinta Allan’s decision to abandon a planned second injecting facility in the CBD.

Loading

Ha Nguyen, president of the Traders Association on nearby Victoria Street, keeps the doors of his cooking school locked during classes to prevent drug-affected people from wandering in. He often has to clean up after people have defecated in the laneway behind his premises.

“The injecting facility itself does a great job to keep [drug use] out of the laneways,” he says. “However, [for] the traders, they see that it’s a drawcard for a lot of users to come into Richmond.”

The sense of unease is undeniable: even the state government’s Victorian Gambling Regulator recently left the area, citing concern over its staff safety.

Yarra Mayor Stephen Jolly, a long-time advocate for the facility, has also been a vocal critic of the state government’s inaction, describing North Richmond in the media as “Disneyland for drug users”.

He says the suburb has been left with an impossible burden, comparing it to a neighbourhood with the city’s only pub. “If there’s only one pub in Melbourne, every alcoholic … everyone looking for a drink would be there … and it would be a tremendous burden for the people living in that area,” he says.

Inside the medically supervised injecting room in Richmond.Credit: Penny Stephens

Heald acknowledged this frustration this week. While the medically supervised injecting room (MSIR) has performed its core mission with aplomb – managing more than 10,000 overdoses without a single death, while ambulance attendances have almost halved within one kilometre of the facility – she agrees with a key finding of a 2023 review that this work came at the expense of a community relationship.

The review found that constant reference to “saving lives” alienated some residents who felt their legitimate concerns about safety and anti-social behaviour were being dismissed. “I can understand how they’re feeling,” she said. “We have to acknowledge that it is ... one of the consequences of the MSIR being here.”

Jolly called Heald’s admission a “brave stand” and a positive development, stating it “warms my heart because... I’ve been arguing that the locals have been gaslit” for years. He said he would now “extend [his] hand of friendship” to the service and would, jointly with the council and community, “work on the strategy to deal with issues”.

The recent removal of temporary fencing has revealed new lawns, pathways and permanent fencing in the area and allowed patients of the next-door health clinic to enter without having to walk past the injecting service.

A direct phone line has been established for the primary school next door to alert security about inappropriate behaviour. The service will also provide onsite mental healthcare through a new partnership with St Vincent’s Hospital, and the public are welcome to tour the facility every Monday and ask questions.

The injecting site has about 230 visits a day, but Heald says only a handful of clients are responsible for dumping used syringes or behaving menacingly. While many users socialise around the facility, she argues the service cannot simply “move people on” without pushing them into other areas, such as the nearby public housing towers.

However, she says the service is stepping up behavioural expectations for clients. “There has been probably previously a bit of a thought that the clients can stay [congregating],” she said. “Our intention is that we will be working with community to be able to say, you can’t be doing that [dropping used needles] here.”

For some long-term residents, the narrative that North Richmond is “the worst it has ever been” is demonstrably false. Judy Ryan, a resident and key advocate in the campaign to open the MSIR, paints a vivid picture of the precinct before 2018.

Richmond resident Judy Ryan.Credit: Darrian Traynor

“It used to be code blue [involving cardiac arrest] all the time,” she said, recalling how she called ambulances hundreds of times, and once found a body in the laneway behind her house.

Loading

Insiders have pointed to a perceived “cone of silence” from the premier’s office, a stark contrast to the government’s promotion of pill-testing services for young people at festivals.

Beyond the community tensions lie the human stories of the service’s clients, many with complex backgrounds little understood by the public.

MJ, a 32-year-old criminology student, said she had started visiting the safe injecting room after a rare neuromuscular condition caused her “excruciating amounts of pain”. After morphine, she eventually turned to heroin to self-medicate and avoid constant hospital visits.

MJ uses the safe injecting room four to five times a week.Credit: Simon Schluter

The injecting room has provided her with a vein finder, a crucial device because her own veins had been damaged, a safe place to inject and, ultimately, a non-judgmental space. Through the MSIR’s assistance, she has secured public housing, a psychologist and access to methadone. A future without heroin is a long-term goal; she acknowledges it is currently her “Band-Aid” for underlying trauma and chronic pain.

She says there is a misconception that everyone who uses drugs is a criminal with a prison record, which makes addiction harder to overcome.

On Monday, International Overdose Awareness Day, MJ told her story to a crowd for the first time and read aloud an open letter titled From the Margins with Hope, written with input from about 50 users of the service.

“I stand here today as someone who isn’t embarrassed to say that I use drugs,” she said. “But I know how rare that is because for so many, the fear of being judged or shamed keeps them silent. That embarrassment is really dangerous.”

MJ, Nguyen, Jolly and Ryan all agree the demand for such services needs to be spread elsewhere – the site is one of the busiest in the world, and there are lines out the door are not uncommon. Last month the Coroners Court revealed that overdose deaths in the state have soared to a 10-year high; heroin is responsible for the largest number of deaths.

Yet Minister for Mental Health Ingrid Stitt was quick to dismiss the suggestion of even roving injection sites. “No, we’ve drawn a line under this in terms of any secondary service, whether that’s mobile or fixed,” she stated.

Victoria Street in Richmond.Credit: Chris Hopkins

Pressed on why the government had abandoned plans for a second injecting facility in the CBD, Stitt cited “a real difficulty trying to find the right location that was going to kind of be acceptable to the CBD community”.

Stitt offered no specific financial commitment to the council to assist with the $400,000 a year it spends cleaning up syringes, but said the government would “continue to work constructively with them on these challenges”. Nguyen has a list of practical requests for the government, including permit fees waived, protective services officers beyond the train stations and grants to create a community plaza near the corner of Lennox and Victoria streets. But Heald remains optimistic.

“I would hope that in 12 months’ time the community can talk about where they can see the changes,” she said. “I want them to be able to say, ‘Look, there are still some issues. However, we have seen that things are a little bit better.’”

Know more about this or another story?

Reach Rachael Dexter securely via ProtonMail (end-to-end encrypted) at [email protected] or message her on Signal at rachaeldexter.58.

Most Viewed in Politics

Loading