The text message arrived at 8.16pm on a Saturday.

It was my cousin Mark, who I had last seen in April.

“There’s a Ferrari in South Australia you might be interested in. Wondering if you remember it used to be silver?”

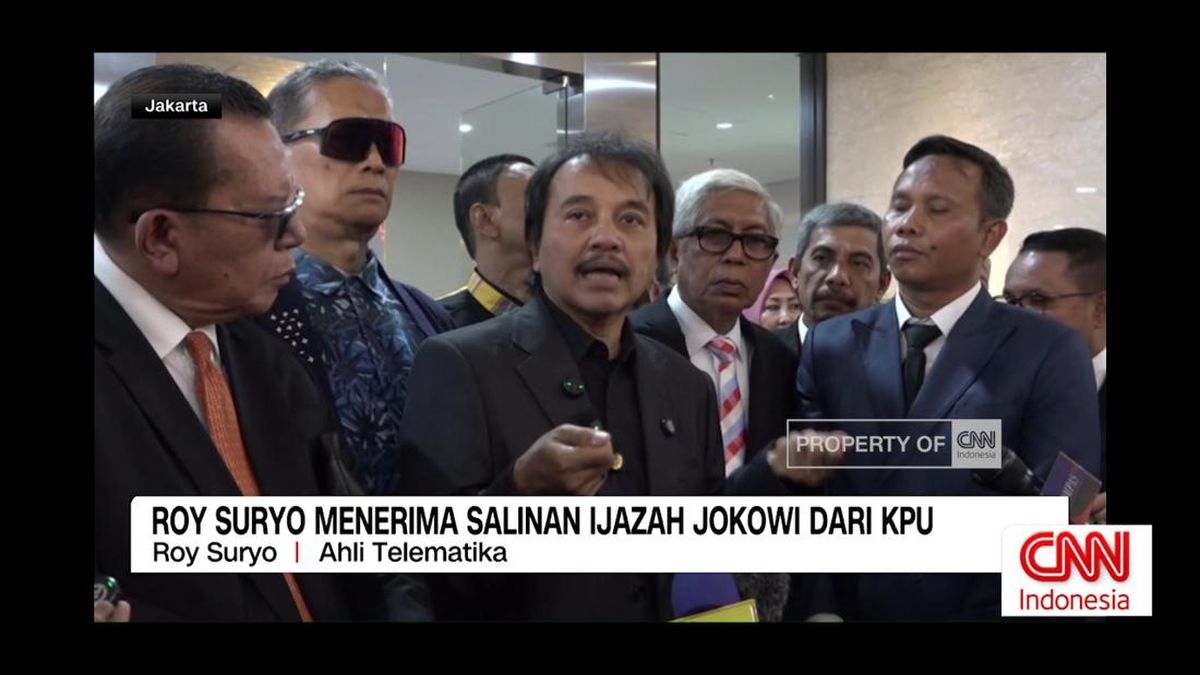

36 years after he sold his 1963 Ferrari 250GTE, Silvio Massola’s Ferrari is back on sale for just less than $1 million. His grandsons James Massola and Mark Viggiani paid it a visit at Richmond Motors in Adelaide.Credit: Ben Searcy

Our grandfather, Silvio Massola, had once owned a Ferrari though my memory of it was hazy.

Silvio had been a successful mechanic, entrepreneur and racing car driver who had raced in the 1953 Grand Prix at Albert Park, at Bathurst and more, in cars he had built and upgraded himself.

Carlo (left), James (aged 3) and Silvio Massola and one of the Bugattis.Credit: Massola Family

In his later years, he used to rebuild and restore old Bugattis and then take them to old car rallies. His favourite, named Papillon, was a baby-blue type 37, but eventually, he sold them off.

My father, Carlo, died suddenly on Good Friday this year and I had barely had a chance to look through his papers. In the fog and the grief of the immediate days afterwards, a friend had texted me, “I don’t think we ever feel grown up enough to lose our parents”.

The comment rattled around in my brain for months afterwards.

In among the few papers I had seen there was a medal that my great-grandfather (called Carlo, like my Dad and one of my sons) had claimed for winning the 1921 Grand Prix of Rome. It was a treasure.

Carlo Massola’s medal for winning the 1921 Grand Prix of Rome.Credit: Massola Family

I had had it framed, along with some beautiful, hand-drawn schematics that Silvio had used to rebuild one of his Bugattis.

I clicked the link Mark had sent, and my eyes nearly fell out of my head.

It was a maroon (dark brown) 1963 Ferrari 250GTE, a close relation to my all-time favourite car, the Ferrari 250GTO. Just 36 of the Gran Turismo Omologato had been made, and they sell these days for well north of $50 million (the highest reported sale price was $US70 million in June 2018).

Approximately 955 of the GTE were made, and it was a close cousin, with the same 3.0-litre, naturally aspirated V12 engine and a stunning Pininfarina body-designed body.

I read through the listing, which included the fact that our grandfather had owned it from 1974 to 1987.

It was much cheaper than a 250GTO but Richmonds, the dealer in Adelaide, wanted $870,900. (The cars originally sold for about $US18,000, much closer to what my grandfather would have paid for it, when new.)

I texted Mark. “We have to go and see this car.”

I emailed the dealership that night and called them on Monday. Aleco Lanfranco answered the phone. After establishing I wasn’t crazy, Lanfranco said he was happy for us to fly over (they were trying to sell it, after all) but they would have to check with the current owner.

I talked incessantly about the Ferrari for a week, bombarding family, friends and distant acquaintances with obscure details and waited for approval.

At night, I went through old photo albums and cassette tapes I had inherited. I found an interview with Silvio from 1997 on a cassette, on Melbourne radio station 88.3FM, about his life, his racing career and his father’s and the 11 Bugattis he had rebuilt by hand over decades.

Silvio Massola (front row, right) in his type 37 Bugatti, Papillon (Butterfly), at a Bugatti rally in country Victoria in the early 1980s.Credit: Massola Family.

And over and over, I asked myself, how could I buy this car?

The owner, it turned out, was racing legend Vern Schuppan. A retired Formula 1, Indianapolis 500 and touring car racer, the Adelaide-based Schuppan was also only the second Australian ever to have won the gruelling 24 Hours of Le Mans.

I emailed Schuppan with a million questions and got a short, terse response.

He was happy for the free publicity, it seemed, but didn’t want to be interviewed as he was busy renovating his house in Portugal.

At least he was on-brand for a famous racing car driver.

Mark and I booked our flights to Adelaide.

Silvio Massola’s 250 GTE at the family home in East Brighton in the late 1970s. The custom plate is SM.013 - Silvio Massola, born 1913. Antonietta Massola is pictured in the background, watering the grass. Credit: Massola Family

Would I get to drive it? Could I start the engine? Would I get to sit in it? Would there be some sign, some “tell”, that would link the car back to Silvio?

Finally, the day arrived.

We arrived just after 10.30am on Tuesday and I missed the Ferrari because I was dazzled by the showroom floor.

A bright yellow Mini Moke, a green Holden Sandman, a cream Rolls-Royce, a rally-ready, black and white Fiat 128, a bright red 1964 Alfa Romeo Giulia Spyder that cost about $80,000 and was slower than my self-driving lawnmower (I’d still take the Alfa over the Ryobi).

The 250 GTE was way up the back, roped off.

My dreams of driving it pretty much evaporated on the spot, all the “clever” things I’d be able to say to convince Aleco and his colleague Andy Morgan to let us have a drive.

I begged, but only a little bit, and I didn’t really even convince myself.

So I walked over to the car instead and made to have a closer look at the iconic Prancing Horse on the front grille. I was kneeling before I knew it. I’m sure I wasn’t first.

36 years after he sold his 1963 Ferrari 250GTE, Silvio Massola’s Ferrari is back on sale for just less than $1 million. His grandsons James Massola and Mark Viggiani paid it a visit. Pictured (r-l) Richmond Motors dealer Aleco Lanfranco, James Massola and Mark Viggiani at Richmond Motors in Adelaide.Credit: Ben Searcy

It wasn’t the most expensive car on the floor – that was a 2024 Ferrari SF90 Stradale hybrid worth about $4 million – but it was the best.

Keep your hybrid V8, Ferrari, I want the V12.

Mark and I started peppering Lanfranco and Morgan with questions. Who did Vern buy this from? Why did they change the colour? When did that happen? Are those 36,946km on the clock real, or did the odometer get re-set when the rebuild happened?

The car had been restored and rebuilt by specialists for Schuppan back in about 2015 and, it turned out, those were original kilometres (not miles).

Could I touch it? Could we open the boot? Could we open the engine bay? Could I sit in it? Could we start the car? And could I drive it?

It was a yes to everything but starting and driving the Ferrari (I asked, many times, but driving the car even briefly would require hours of maintenance afterwards).

Mark went first. At about 5′8″ he’s a little shorter than me. He managed to squeeze in, but his knees knocked the steering wheel. The engine bay was bigger than the cockpit.

Mark Viggiani (left) and James Massola behind the wheel of a Ferrari 250GTE their grandfather Silvio owned for more than a decade.Credit: Ben Searcy

We swapped. My head touched the roof, I could barely fit behind the wheel (I’m a bit over 185 centimetres, or 6′1″, and a bit overweight) and my knees were so jammed in they were level with the top of the steering wheel.

I kept noticing small details. The handbrake was on the floor, not in the centre console.

This was a racing car, but it was also a luxurious touring saloon. It was the first Ferrari to ever have four seats (known as a 2+2, but the back seats were just for little kids) and the fact that there were no rear seat belts proved how impractical it was.

There was an ashtray between the two rear seats, however, which was handy if your eight-year-old decided to take up smoking.

The steering wheel was extraordinary.

Inside the cockpit of the Ferrari 250 GTE.Credit: Ben Searcy

Thin, reedy, made of a wood that felt light but strong, with a strip of metal running through the inside of it to reinforce it.

Aside from the speedo and the tacho, there were four simple gauges and an analogue clock.

Benzina, acqua, oglio and ampere.

Petrol, water, oil and power.

What else do you need to go?

The top speed on the speedo was 300km/h, but the real top speed was about 230km/h, the dealer told us.

I wasn’t sure if it was four or five speed so, after making sure no one was watching, I depressed the clutch and rowed through the gears of the manual, feeling each notch click heavily into place as I tried it out.

It was a four speed.

Carlo Massola behind the wheel of his Diatto racing car in the late 1920s. Carlo raced and won grand prix in Europe before moving to Australia to open a Fiat dealership and race.Credit: Massola Family

As we rode in a taxi to the airport, we chatted with our driver Rafeq about Yemen (he had left 17 years ago and called Australia home) and Palestinian recognition.

But when we got to the airport we fell silent for a while and pondered the sheer majesty of the 62-year-old super car that had once been our Nonno’s Ferrari.

The first Carlo Massola, our great-grandfather, had been sent to Australia to open the country’s first Fiat dealership in Melbourne in the 1920s.

Loading

He had died a decade later, after a bad crash in a race in Aspendale in the early 1930s led to pneumonia and an early death.

Our grandfather Silvio had died in 2011, at the age of 97, and my father Carlo had left us just a few months earlier. We had had one last adventure, crossing the Nullarbor together in an EV in January 2023.

But perhaps the three of them had been present – Carlo, Silvio and Carlo – just for a moment, as Mark and I took one last look at the Ferrari and thought about the long journey from Torino that had brought our family to Australia for Fiat of Turin.

I’ll never own a Ferrari.

But the trip to Adelaide, and the time with my cousin, had been well worth it.

Most Viewed in National

Loading