When question time began in the state parliament on September 9, there was a rawness to Victorian politics.

Three days earlier, two children, 12-year-old Chol Achiek and his 15-year-old friend Dau Akueng, were hacked to death in a suburban street not far from their homes. The killing of Chol by three people wielding machetes was captured by CCTV camera across the street, along with the boy’s dying screams. The footage is sickening to watch and impossible to unsee.

In the aftermath of these savage killings, Opposition Leader Brad Battin, a former cop, spoke to a firefighter who was among the first emergency workers to arrive at the crime scene. “Their words to me was ‘I don’t know if I can ever go back to work, it is the worst thing I have ever seen in my life’,” Battin says. “These kids were so innocent, and it felt like they were hunted on the streets in Victoria.”

On a floor of state parliament – a world away from Cobblebank, a newly established suburb near Melton in Melbourne’s outer north-west where Chol and Dau lived – Battin’s opening question to Jacinta Allan was laced with despair and revulsion at what had happened. “Premier, how has it come to this under your government?”

In response, Allan deplored the senseless violence and expressed sympathy for the unimaginable grief felt by parents whose sons never returned from playing basketball.

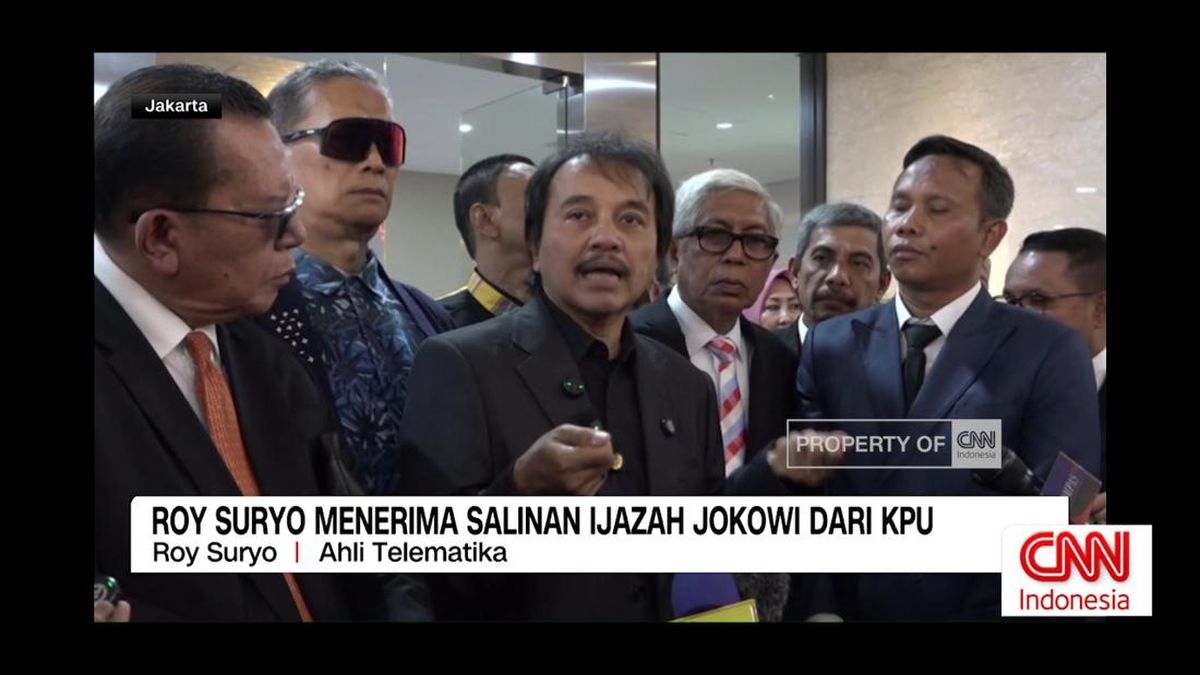

Mourners at the funeral of 12-year-old Chol Achiek.Credit: Simon Schluter

“We all want answers,” she said. From there, the question time dissolved into rancour, with Battin ejected from parliament.

There are crimes that stop a city, even one as large as Melbourne. There are also crimes that can jolt the way we think about our state, where we are heading and whether the right people are in charge.

In the lead-up to last year’s Queensland election, the murder of Vyleen White, a 70-year-old grandmother, was one of those crimes.

White had driven to her local shopping centre in Redbank Plains, a suburb of Ipswich, with her six-year-old granddaughter to pick up some groceries. It was a late summer, Saturday evening. It ended with White bleeding to death in the car park from a stab wound to her chest, her granddaughter screaming in the shopping centre for help, and a youth in jail for murder.

All because a group of teenagers tried to steal a 15-year-old Hyundai Getz.

This was the crime that inspired then opposition leader David Crisafulli’s “adult crime, adult time” mantra on juvenile justice, a catchphrase which seven months later helped propel the LNP into government in Queensland for just the second time this century.

The Queensland election was not decided by a single issue. No state election ever is. But crime in Queensland became emblematic of a bigger political perception; a tired government that had either stopped listening or was incapable of adequately responding to a fundamental community concern – that people didn’t feel safe.

A question looming over Victorian politics is whether Battin, in his unrelenting crusade on crime, can follow the same path Crisafulli took into office.

The latest statewide crime statistics, released last week by the independent, Crime Statistics Agency, confirm that crime is a deadly serious problem in Victoria, with rates of offending at previously unrecorded levels.

Loading

Some of the fastest growing types of crime are offences that, for the past year, have lit up the phone lines of talkback radio and the electoral offices of MPs – car thefts, burglaries and shoplifting. Reported incidents of family violence have also soared. Deputy Commissioner Bob Hill, a policeman 40 years in the job, describes it as a perfect storm.

Despite this bleak picture, some of Battin’s Liberal colleagues are worried that the party’s crime focus is too singular and at risk of becoming shrill.

Some of them carry scars from 2018, when in the wake of the Moomba riot and concerns about lawless youth gangs, a narrow cast, law and order campaign culminated in electoral disaster for the Matthew Guy-led Coalition.

“When was the last time we talked about health, public transport or energy?” one frontbencher says. “There has been a decision that these issues will not be talked about, that we will only talk about crime.” Another says of Battin: “He is comfortable talking about crime, but he has got to learn to be comfortable talking about more than just crime.”

Battin’s response, in an interview with this masthead, is that there will be plenty of time given to other issues between now and the next state election, which is still 14 months away. But he says that right now in Victoria, there is no more important issue than crime.

“It is not us raising this,” he says. “It is people across the community raising it. That is why it is a big issue. The priority of any government should be to keep you safe and at the moment, people aren’t feeling safe.”

Loading

To illustrate his point, Battin runs through a series of community events he attended across Melbourne’s western suburbs on Thursday.

His day started with a survey of voters at Watergardens train station at 7am, continued with a housing forum and meeting with small business associations at Moira Deeming’s electoral office in Caroline Springs, and ended in Taylors Lakes at a local sports forum and lastly, a community forum about crime.

Battin says that at every meeting, people just wanted to talk about crime.

Experienced campaigners from both sides of politics say that to understand the electoral potency of crime, you need to consider more carefully what drove both the 2024 election result in Queensland and 2018 result in Victoria.

In Queensland, crime was one of four key issues the LNP campaigned on against a Labor government that had been in power for nine years and a hand-me-down premier in Steven Miles. The others were health – in particular ambulance ramping and a collapse in regional maternity services – housing and cost of living.

Within the Crisafulli campaign, crime was seen as not a vote changer in itself, but a “proof point” that the government had stopped listening. “It wasn’t necessarily a crime election,” one senior LNP figure says. “Crime resonated, but a lot of people were fed up with Labor being out of touch.”

Scott Stewart, a minister in both the Palaszczuk and Miles governments in Queensland, lost his Townsville seat on the night the LNP was swept to power. He believes crime was the issue that cost him his job. Crime rates were actually falling in Queensland at the time of the election. Labor’s argument was that preventing crime was more complex than a four-word slogan. Stewart says this is not what people wanted to hear.

“They just wanted it stopped,” the former school teacher says. “And the only way that they could see it was that the LNP were going to lock up these kids if they committed a crime. What we tried to do is just say, ‘look at all the policies, not just one,’ but of course, that doesn’t resonate with people. People who had their car stolen the night before, they didn’t care.”

Queensland Premier David Crisafulli speaks to media after being sworn in.Credit: Matt Dennien

A former Victorian government minister who served in Daniel Andrews’ first term of government says the 2018 election result is also misunderstood. Guy’s promise to “Get Back in Control”, a slogan painted on the side of a bus which served as a mobile campaign headquarters, fell flat not because crime didn’t matter, but because Labor had already responded to the problem.

Victoria’s crimes statistics from 2016 and 2017 show that crime was a rising problem in the state then, as it is now. But after the Moomba riot, when members of the Apex gang, a multi-ethnic youth gang centred in Melbourne’s south-east suburbs, rampaged through Federation Square, the Labor government acted decisively.

Lisa Neville, a policy centrist, was made police minister and with then attorney-general Martin Pakula, worked with Victoria Police and the Justice Department to develop a broad policy response. More than $2 billion was spent to hire more than 3000 new police and provide them with whatever equipment police command asked for. Bail laws were tightened.

The prison population surged, including the number of accused people on remand. Civil libertarians were appalled but crime rates went down. In the year of the 2018 election, they dropped by nearly 8 per cent. “We were seen to be doing things,” the former government minister says.

Loading

Labor didn’t campaign in 2018 on crime. Daniel Andrews, in his final pitch to readers of this masthead, didn’t mention it once. He didn’t need to. He talked about removing level crossings, building schools and hospitals, delivering major road and rail projects and promised free kinder. This is consistent with Andrews’ approach to law and order throughout his time as premier – give the police whatever they ask for and change the conversation.

A review of the 2018 election campaign by Tony Nutt, a former director of the federal Liberal Party and chief of staff to John Howard, found that crime was a vote changer for a vanishingly small number of people. The view also concluded that Guy’s campaign suffered from a bigger problem. “In the minds of key voters in early 2018 Matthew Guy and the Victorian Liberals were largely unknown quantities and remained so for far too many electors through to election day.”

A political strategist who worked for Andrews says crime to a state Labor government is akin to immigration for a federal Labor government – the more you are talking about it, the more your opponents are winning. This doesn’t mean Labor can ignore crime. Proof of this in Victoria is the 2010 election, when a long-term Labor government was too slow to respond to growing community concerns about crime and safety on public transport.

Ted Baillieu, the last Liberal leader to win a state election in Victoria, says crime was an important issue leading into the 2010 election, along with concerns about corruption.

Ted Baillieu, with then chief commissioner Ken Lay, announces more protective services officers will start work at train stations in 2012.Credit: Penny Stephens

His signature law and order policy – a promise to put nearly 1000-armed protective service officers on trains and station platforms – was ridiculed by the government and resisted by police command but endures today, along with the establishment of IBAC.

Baillieu’s political mantra during that campaign was that “sentencing should align with community sentiments”. It is a nuanced message compared to the blunt slogans of both major parties today.

Loading

Where Battin spruiks his “Break Bail, Face Jail” plan, Allan says her “Tough Bail Bill”, which has progressively come into force this year, is keeping more young people behind bars.

On the morning the latest crime statistics were released, Police Minister Anthony Carbines noted the number of young people on remand was up 26 per cent from the previous year and the number of adults on remand up by 46 per cent. In Victoria, filling jails is cited as a measure of success.

“We need more prison officers and more prison beds open,” Carbines says.

“We need more police prosecutors to charge and process more people through the courts, and we need more magistrates to hear those cases.”

The Victorian government signalled it had changed its approach to crime in March this year, when Allan revealed her plan to undo one of Daniel Andrews’ last reforms – a requirement for bail justices, magistrates and judges when dealing with children to use remand as a last resort.

Loading

The laws were tightened further this week when a new bail test for “high harm” offences came into force. This makes it almost impossible for people accused of repeated home invasions, carjackings, armed robberies and burglaries to be granted bail. Allan is promising to do more.

The changes suggest that, in contrast to the ousted Queensland Labor government or the Victorian government Baillieu defeated in 2010, the Allan government is alive to the electoral risks of crime.

The Victorian election will be decided not by the next carjacking or home break-in, but whether voters think the government listened to them about a serious problem.

Start the day with a summary of the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up for our Morning Edition newsletter.