Blanche d’Alpuget and I are about 30 minutes into lunch, on a delightful spring day of the kind only Sydney can dish up, when she makes an observation. “You do realise you’re talking about Bob all the time, don’t you?”

She makes it perfectly politely, and the 81-year-old is right. My line of questioning thus far has been Bob Hawke-centric. “Shall we talk about something else?” I ask.

“I think so,” she responds, and laughs her infectious laugh, made a little more guttural by a recent chest infection (her health has suffered since Hawke’s death in 2019, something she puts down to the somatic consequences of grief).

We are lunching at Chiswick in Sydney’s Woollahra, in a renovated greenhouse set amid a cottage garden from which the menu is fashioned.

We are here to discuss a new book about her life – as a writer, mother, Indonesian-ist and, yes, Australia’s most famous mistress-turned-wife. D'Alpuget says she was “nagged into” Fridays with Blanche, a book of conversations with author Derek Rielly. It forms a companion piece to Rielly’s well-received Wednesdays with Bob, about, well, you-know-who.

The concept is similar – although the Blanche version features cameos from famous friends including actress Miriam Margolyes (who, we learn, was present at the dinner d’Alpuget hosted to stage a rapprochement between Hawke and Paul Keating), Thomas Keneally and former Labor minister and head-kicker Graham Richardson.

The book is anecdotal and engaging – it dances around from d’Alpuget’s youth as the daughter of a swashbuckling journalist and his heiress wife, to her life as a teenage runaway and, later, diplomat’s wife in Indonesia in the 1970s.

It covers motherhood, d’Alpuget’s career as a biographer and fiction writer, and her intense dive into spiritualism, which culminated in training as a priest with the Independent Church of Australia.

Studded throughout, of course, are her love affairs, most notably with Bob, but most definitely not limited to him.

“I very much like male company,” she tells me. “I like female company, too, but I think I feel more relaxed with men … I think because they laugh a lot, have you noticed? Men are given to hilarity and fun.”

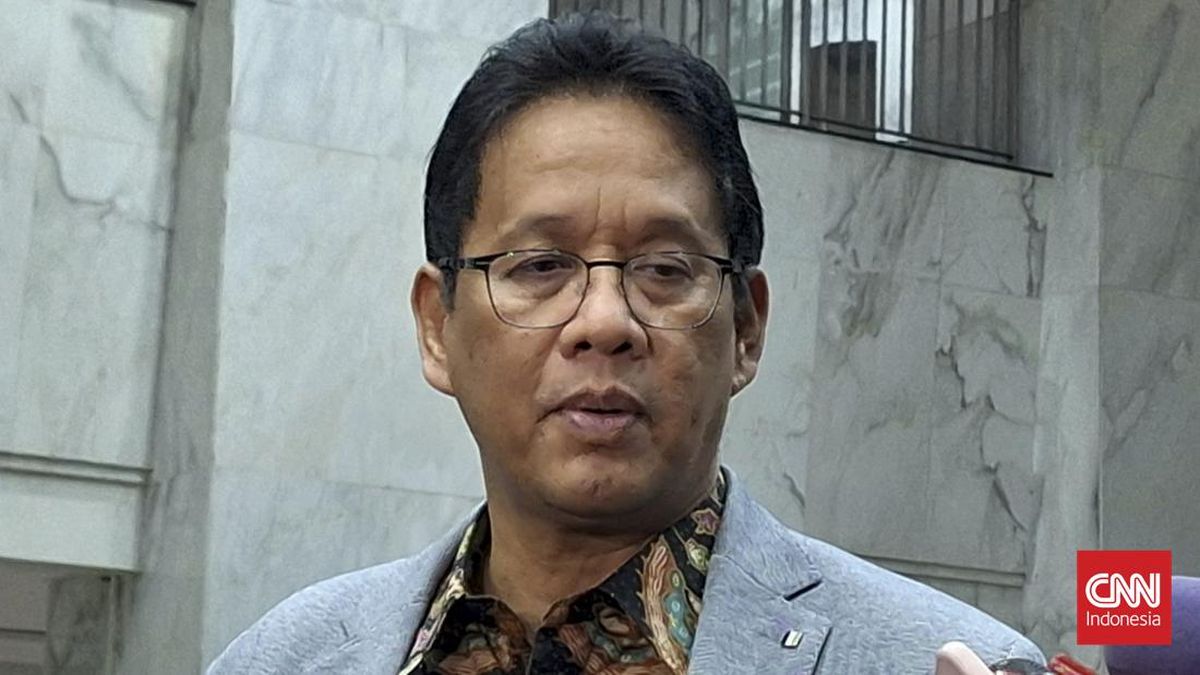

Blanche d’Alpuget at lunch at Chiswick.Credit: Jessica Hromas

Fridays with Blanche has more sex in it than any book I have read in a long time, so much so that I felt like a prude as I read some parts. I have a similar response when d’Alpuget, later in our lunch, talks freely about her personal trainer’s “cock”. It is difficult to know how to respond to such a line of conversation. I don’t have a personal trainer.

For our entree we share a plate of “barra-masalata” with vegetable crisps – a take on traditional taramasalata but with smoked barramundi. It is creamy and delicious.

The book, d’Alpuget says, was a compromise. Her agent wanted her to write her autobiography but she “didn’t want to go into all that stuff”.

“Some of my childhood was quite traumatic and I didn’t want to be raking that up again,” she says. “And to write, you have to be passionate about wanting to do it because it takes so much of your energy.”

D'Alpuget should know – after she wrote her acclaimed biography of Hawke, published in 1982, she was entirely sick of him, she says. She moved straight on to a novel about Israel (Winter in Jerusalem, published 1986), for which she travelled there, staying for several months to research it.

When Hawke became prime minister he found out her number and rang her. What did he say? “‘Gidday’,” she mimics, and laughs that laugh again.

It is hard not to ask d’Alpuget about the love affair, even though, as the book shows, it is probably the least interesting thing about her. Her relationship with Hawke is such a long-running thread throughout d’Alpuget’s life – from their first meeting in Jakarta in 1970, to his death in 2019 – that it is difficult to disentangle it from her plentiful other adventures.

The barra-masalata with vegetable crisps.Credit: Jessica Hromas

The pair had periods of intense devotion – like in 1978, when Hawke drunkenly proposed to her (problem: he was married to Hazel Hawke, mother of his children), and periods of estrangement, like when he retracted the proposal.

Divorce from Hazel, he told her, could cost Labor 3 percentage points off its primary vote. There were years when they didn’t speak.

As the book painfully describes, through an interview with Hawke’s daughter Sue Pieters-Hawke, when the ex-PM left Hazel, his wife of 39 years, for Blanche, his mistress, in 1995, he was not unambivalent. On the morning of his arranged departure, Hawke woke up next to his soon-to-be ex-wife “crying and just clinging to her”, according to their daughter.

It was Hazel who got Hawke in the shower, helped him pack and drove him away from his marriage to his next destination – to be finally united with Blanche.

D’Alpuget and Bob Hawke just before the publication of her biography of him in 1982.Credit: David Bartho

Wasn’t it emotionally devastating to be picked up and put down so many times by this man, over decades?

“When I was first in love with him, it was emotionally devastating,” she says. “I realised he was getting his leg over everything he could, and women were throwing themselves at him. They really were flinging themselves.”

For d’Alpuget “the solution was to have other men … other lovers”.

Did that work?

“It did,” she responds, crisp. “What I always knew – what I knew intuitively because he never said it to me – was that I was his favourite. I just knew that. And as it turned out, I was correct.”

But enough about Bob. Our mains have arrived: we have both ordered the same dish of John Dory fillet. On the side we have spring asparagus and hand-cut chips with rosemary salt and aioli.

The dory at Chiswick.Credit: Jessica Hromas

D'Alpuget divulges that she has mostly lost her sense of taste, the result of long COVID, part of the bout of ill-health that plagued her since she had breast cancer in 2020. (The mastectomy and subsequent breast reconstruction is chronicled in the book, in a chapter entitled “To rebuild the perfect teardrop breast”.)

I remark that, apart from being a fun read, Fridays with Blanche is a fascinating social history of the generation of women to which d’Alpuget belongs, who dealt with male predation and sexism in their youth but were liberated by the women’s movement.

Recounting a short stint as a journalist at a women’s magazine with a staff of smart women writing silly stories, d’Alpuget describes them as “racehorses pulling dung carts”.

“I mean, women were very unhappy,” she says. “They were prisoners. They were forced to become housewives when they could have been lawyers or doctors or …”

“Prime ministers?” I say.

“Prime ministers,” she agrees.

D'Alpuget was raised as the single, adored child of her Darling Point household. Her father, Louis d’Alpuget, was a famous yachting journalist, a cigar-smoking, Hemingway-esque figure who loved outdoor sports and women. He taught his daughter how to fight, sail, tie knots, fish, fire a gun and set a trap.

He had affairs, which greatly distressed Blanche’s mother Josie, and her distress was very evident to young Blanche. Once, in extremis, Josie burst into her young daughter’s bedroom, threatening suicide. D'Alpuget says that experience is “wedged very deep” in her.

“In the pure virgin gold of a child it was a big thumbprint,” she says. “That was part of a cumulative dynamic between them, and I think it did make me determined never to be dominated by a man.”

Louis d’Alpuget was charming but could be what we would now call abusive. When 17-year-old Blanche began an affair with a much-older, married Polish man, her father beat her up, and she fled the family home.

A side dish of asparagus.Credit: Jessica Hromas

Ejected by a women’s hostel on morality grounds, the young d’Alpuget tried to rent a flat in Potts Point. She was raped by the real estate agent who showed it to her as his secretary stood outside the door.

In the book d’Alpuget is quoted as saying, about this incident, that “it made me realise that one is responsible for one’s own life and what happens”. What did she mean by that?

“I remember where I was,” she recounts. “I was standing next to the El Alamein Fountain [in Kings Cross] and I just surveyed where I was, where I had come from, and what I had done to get there.

“I had this realisation. I suddenly grew up in five minutes.”

What were you thinking? “I was telling myself, ‘I am responsible for myself’ … I never had that victim attitude. I thought, ‘Everything has cause and effect’.”

I ask her what she bore responsibility for.

“I bore the responsibility of being foolish and naive enough to tell him I’d run away from home.”

Blanche d’Alpuget as a young reporter in 1965.Credit: Fairfax

She pauses and says, with some heat: “And his bloody secretary stood guarding outside so nobody would come and interrupt him. She knew, and I wasn’t the first.”

The strength of male sexuality is a theme of d’Alpuget’s conversations in the book. She says women don’t understand “the force of testosterone”.

I ask whether men have some obligation to control this force. “Of course, and they try to,” she says. “They’re civilised into doing that but it’s an animal that will escape. It’s a wild animal that will try and get out, and it does.”

As we finish off our mains our lovely waiter supplies petit fours, unasked for.

Some of the most affecting parts of the book are about d’Alpuget’s spiritual explorations, and her thoughts on love and grief. She describes her mother’s last days and how, after her mum died, peacefully, d’Alpuget’s first impulse was to ring her up and say, “Hey Mum, guess what?” to discuss the experience.

The billCredit:

As we nibble the treats – a teeny meringue and a dollhouse-sized carrot cake – we discuss how much grief can surprise you. “It comes up and jumps on you,” she says.

Death, she says, “is inexplicable. It’s a mystery.”

She lights up talking about her nearly three-year-old granddaughter, and how much she loved motherhood. She was estranged from her son, Louis, for a period during his adolescence, but now they are close and talk several times a week.

D’Alpuget has always been a spiritual seeker, something she puts down to an out-of-body spiritual awakening as a child and, later, her time in Java in the 1970s, which was a “mystical” place, she says.

Part of her spiritual practice now is gratitude.

Loading

“One of the main keys to a happy life is gratitude because it turns the ordinary into something beautiful. It raises your morale.”

I ask her what she feels grateful for. “Everything!” she cries. “The sunshine, those plants, the way the palm trees are moving. Lunch! You!”

The photographer wants to get some portraits of d’Alpuget and moves her to a light-filled room next to the cottage garden. Sun streams in as butterflies cruise the herbs outside.

D’Alpuget fusses over her appearance, which is flawless, while posing like a proper sport for her photographs. Afterwards, I walk her through the gardens to her waiting driver. I feel grateful, too.

Start the day with a summary of the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up for our Morning Edition newsletter.