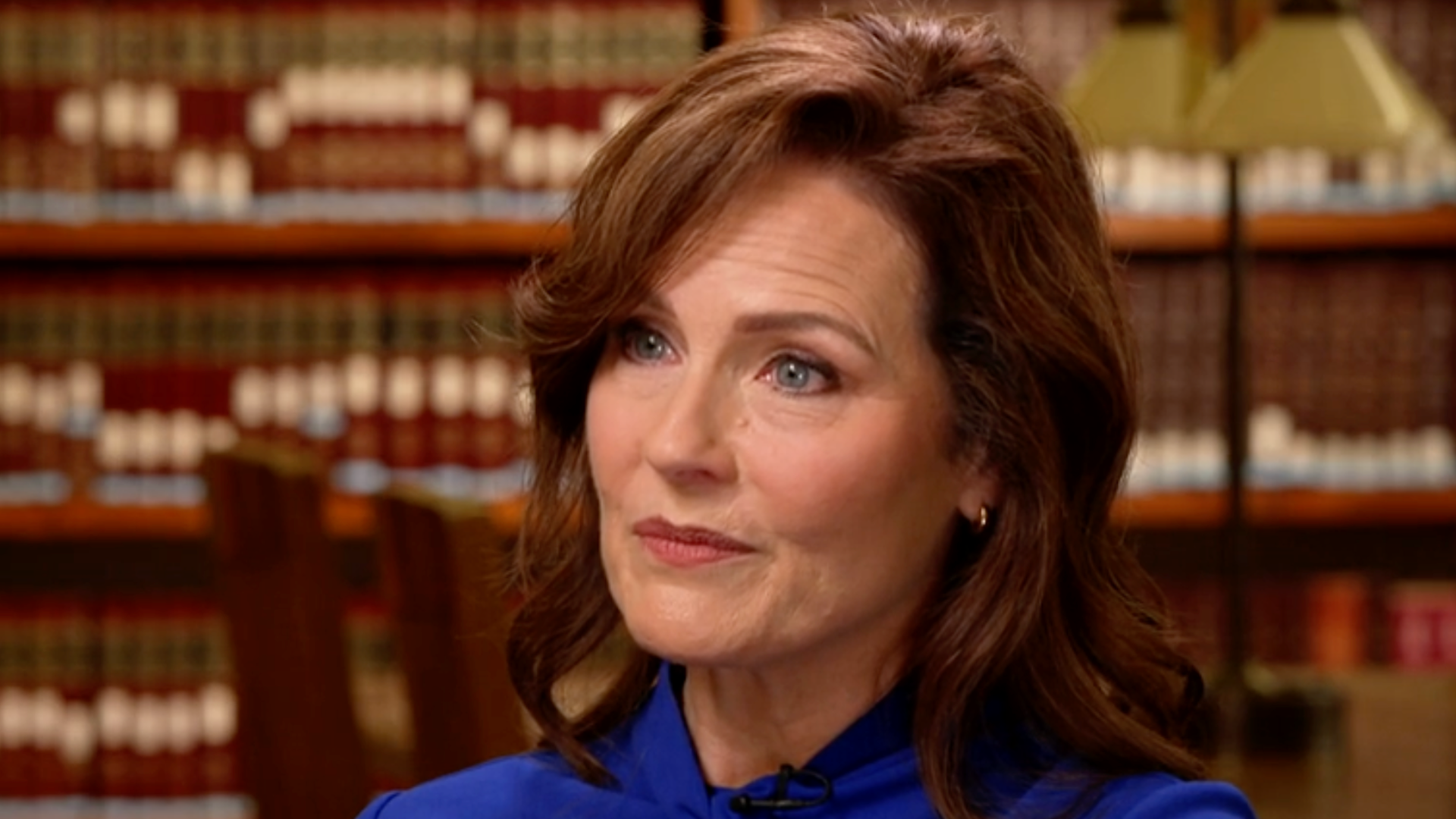

Barrett says her kids have had to be "unpopular"

Whenever Justice Amy Coney Barrett arrived at an auditorium or a library or a university last month to discuss her new book, she encountered a familiar sight: protesters.

They lined the streets, chanting and carrying signs. One wore a handmaid's costume, a symbol of oppression. Another was dressed as liberal icon Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, whose death in 2020 created a vacancy on the Supreme Court that President Trump would fill with Barrett.

For Barrett, protesters have become routine, another logistical wrinkle in her everyday life, much like the ones who regularly gather at her home outside Washington, D.C., where she lives with her husband and younger children. What surprises her, she told me in a wide-ranging interview in her chambers late last month, is how she can let it roll off her back.

"If I had imagined before I was on the Court, how I would react to knowing that I was being protested, that would have seemed like a big deal, like, 'oh, my gosh, I'm being protested,'" she says. "But now I have the ability to be like, 'Oh, okay, well, are the entrances blocked?' I just feel very businesslike about it. It doesn't matter to me. It doesn't disrupt my emotions."

A fury of protests against conservative justices erupted in 2022, when news leaked that the Court was poised to overturn the landmark decision Roe v. Wade. Barrett, a conservative in the mold of her former mentor and boss Antonin Scalia, was a particular source of ire. Replacing Ginsburg, whose legal career was grounded in women's rights, she provided a key fifth vote to overturn Roe and let each state decide whether to allow abortion or not. But the decision also unleashed something much darker.

On Friday, a California resident was sentenced to eight years in prison for the attempted assassination of Justice Brett Kavanaugh, who also voted to overturn Roe. Court papers revealed the perpetrator had also mapped out the homes of three other conservative justices, including Barrett's. Death threats have not gone away, and security remains high at their homes and whenever they appear in public.

I asked Barrett if she is ever afraid. Her response was immediate and emphatic: "I'm not afraid."

"You can't live your life in fear," she continued. "And I think people who threaten — the goal is to cause fear. And I'm not afraid. I'm not going to reward threats with their intended reaction."

That kind of mental discipline and self control, even in the face of threats and extreme criticism, reflects an outlook that has guided the 53-year-old Barrett much of her life.

"I don't make decisions emotionally. I try very hard not to let emotions guide decisions in any aspect of my life. The way that I respond to people, the choices that we make," she continues, adding with a laugh, "apart from maybe some impulse buys of clothes or something."

That outlook is also reflected in her approach to the law.

On the Supreme Court, Barrett's opinions are highly analytical. She doesn't like to decide more than the issue at hand, which is one reason she has parted ways with conservative colleagues who would rather swing for the fences, like in a case two terms ago when the Court ruled states cannot remove Trump from the ballot. Barrett agreed on the bottom line, but had a more limited approach.

As a former law professor, she can be formalistic and technical, qualities that also can separate her from other conservatives, as in a 2024 case that attempted to hold the Biden administration responsible for suppressing speech on social media during Covid.

Now entering her sixth year on the Court, Barrett continues to defy stereotypes. Critics span the political spectrum, not only Democrats after she voted to overturn Roe, but more recently Republicans in the wake of decisions at odds with President Trump. She is "confounding the Right and the Left," as the New York Times put it, raising hopes and fears on both sides.

That's partly because, in decades past, some conservative justices have turned out to be anything but conservative. Would Barrett, too, go that route? And it's also in part because of a fundamental misunderstanding about the Court, reflecting an idea that the justices are mere political actors who should stay on their respective sides, regardless of the law.

"That is a notion that I try to disabuse people of in the book," she says.

Correcting some of those public misperceptions that the Supreme Court is driven by politics or outcomes or is loyal to Trump is one of her main goals with her new book, "Listening to the Law." She is part teacher, part tour guide, taking the reader inside the Court and highlighting some of its most controversial decisions to explain how the justices interpret the Constitution and the differences in conservative and liberal philosophies.

And there is no case more controversial than the 5-4 decision overturning Roe, Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Whole Health. Barrett uses it to explain how she and the Court's conservative majority interpret the Constitution with a method known as "originalism," focusing on the Constitution's original meaning, the way the public understood it when it was adopted.

In our interview, Barrett said she was drawn to originalism when she read Justice Scalia's opinions in a constitutional law class during her second year at Notre Dame Law School. She said she was frustrated after a first-year criminal law class, reading liberal decisions of the Warren Court and finding them to be "unmoored." Scalia's opinions, with his originalist framework, made sense to her.

"I think I am different in style than Justice Scalia. I don't think I'm different in substance," she said. "I think one thing that was important to Justice Scalia is fidelity to his analytical framework, so fidelity to textualism and originalism, even when it led to places that he didn't want to go."

Scalia, for example, upheld flag burning as a First Amendment right, even though he said "if I were king, I would not." With Barrett, an example is the death penalty. She upholds it as constitutional, even though it is at odds with her religious views.

And that framework, she says, is how she approaches the cases involving Trump. While politicians, the media and the public are focused on the current occupant of the office, she says "the Court has to take the long view."

"The way that we have to view cases is about the presidency, not about the president. We have to make a decision that's going to apply to six presidents from now, and that's how I try to view the law," she says. "So in the same way that I do try to erase particular policies, or substitute in ones that I like or dislike — to try to maintain neutrality — I try to do that with the presidents too, because it can't turn on the president."

Her critics aren't convinced, but Barrett seems unfazed by the attacks on her judgment or her character. In our conversation, and in multiple interviews with those who know her, she comes across as someone with a strong sense of self and an equally clear view on the right way to interpret the Constitution. Unlike some justices, she says she doesn't monitor what journalists and law professors and politicians say about the Court. She has seen them get it wrong. It doesn't matter to her.

"If I could have, especially as a 16-year-old, imagined that I would not care or be impervious to being criticized and mocked, I would have been very surprised," she says. "And so I am glad, because I think this would be a miserable job if you let yourself care, if you let yourself be affected."

Barrett first walked through the fire after Trump nominated her in 2017 to the Chicago-based federal appeals court. In her Senate hearings, she withstood withering attacks on her faith, notably when then-Democratic Senator Dianne Feinstein told her, "the dogma lives loudly within you." Her steely performance impressed conservatives and helped get her on Trump's Supreme Court shortlist.

Barrett was astonished by how she was portrayed by the media. (She said a cousin told her "the person they were describing is not the person that I've known my whole life at all.")

A mother of seven, Barrett is a devout Catholic and proud daughter from a large and supportive family with deep roots in New Orleans. Before becoming an appeals court judge, she was a popular and respected Notre Dame law professor with sparkling credentials. Always a high achiever, she had received full scholarships to college and law school at Notre Dame, where she was top in her class (and met her future husband) and earned highly competitive clerkships with towering conservative icons, Judge Laurence Silberman and Scalia.

"One thing that I really disliked was this idea that I had no backbone, or that I was just this subservient woman in some way," she said, "because I felt like I am anything but that."

She had set goals for her life early on, and she made conscious and methodical choices to reach them. She wanted a big family like she grew up with, but, of course, she would work, so she wanted flexibility in her career.

"I really admired my parents, I really admired my grandparents, and I thought, if I want to be the kind of people that they are, I have to make definite choices," she told me. "I have to decide what my values are, what my priorities are, and make definite choices and prioritize those kinds of things."

Thinking about law school after college, she says she remembers sitting in her dorm room at Rhodes College and making a list of pros and cons, focusing on what mattered to her and "I just reasoned my way to it." (Barrett, always analytical, mentions in her book that her life runs on to-do lists, but she also is partial to pro/con lists.)

She's now the only justice on the Court who didn't attend an Ivy League school, but Barrett says she didn't care about labels or what was considered "the best school." She didn't even apply to Harvard. She opted for Notre Dame over the University of Chicago, for instance, not only because she could prioritize her Catholic faith, but that it also offered a full scholarship. That meant no big student loans that would force her into an all-consuming, high-paying law firm job after graduation.

Searching for a more accurate way to describe herself, Barrett uses the term "Steel Magnolia."

"I've done a lot of traditionally feminine things. I have a large family. I've made unconventional choices in that way. And I'm not sorry to be feminine," she said. "But I don't feel like I have to sacrifice that part. I think you can be traditional in some of those ways, and still have grit or the backbone or the spine. I felt like I had the grit."

"Grit" is a word she uses more than once in the book when talking about strong women she admires, like her great-grandmother, a widow who raised 13 children in a tiny house "bursting at the seams" during the Great Depression. "Somehow she always managed to find the resources, space and time," Barrett writes.

Throughout our conversation, I'm struck by something she wrote early in the book, when she mentions advice her father gave to her and her siblings: "Control your emotions, or your emotions will control you."

It's similar to advice Justice Ginsburg liked to share from her mother: "Don't be distracted by emotions like anger, envy, resentment. These just zap energy and waste time." Ginsburg would say her advice came in handy at the Court, because she learned that reacting with "anger or annoyance will not advance one's ability to persuade."

I asked Barrett if she, like Ginsburg, drew on that advice at the Court.

"Yes, in this job, I think it's part of the tuning out, that I can't let what people say…certainly not affect the decisions that I make, but even affect how I feel," she says. "If I let that in, and then let that affect my mood when I go home or when I'm relating to people, then that needs to be kept out."

Having that mindset, Barrett says, is one of the things she's most proud of as justice, because that wasn't how she felt as a young teenager growing up in a family of nine.

"I felt very conspicuous. We would go into restaurants, and you could see people turning around and counting and looking," she says. "In the preteen and teenage self-conscious years, I thought, I just want to be unnoticed. I'm never gonna have a family that attracts attention."

Barrett rarely shows the kind of rhetorical fire or hyperbole some of her colleagues regularly exhibit. Stylistically, as she says, she is no Scalia. But with the Court increasingly under strain as it grapples with dozens of emergency requests from the Trump administration, Barrett exhibited a flash of pique last term, responding to a fiery dissent by Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson in the case limiting the use of nationwide injunctions.

Jackson, a Biden appointee and the Court's newest member, accused the Court of engaging in "legalese." Barrett, speaking for the majority, responded: "We will not dwell on Justice Jackson's argument, which is at odds with more than two centuries with of precedent, not to mention the Constitution itself."

In the months since, Jackson has only ratcheted up her rhetoric as the Court has issued temporary orders in a range of cases brought by the Trump Administration. In one emergency order last month, on whether Trump could cancel grants to the National Institutes of Health, Jackson impugned the conservatives' motives.

Jackson accused them of having "no fixed rules" except "this Administration always wins" something Barrett pointed out in an event last month was obviously false. (Just one high-profile example: The Court ruled against the Administration's deportation of Kilmar Albrego Garcia and ordered it to work toward his return to the U.S.)

Still, Barrett insists that kind of language doesn't affect her relationship with Jackson, and that she works to have relationships with all the other justices. She says she enjoys talking about the law with Justice Elena Kagan, also a former law professor who, like Barrett has a more formalistic approach to the law than the Court's two other liberals, even though it leads them to very different places.

In a recent interview, Bari Weiss of The Free Press asked Barrett to give one word for each of her colleagues. For Kagan, Barrett chose "analytical." That's a word she also used in our conversation to describe herself.

"You can't take it personally, and so I think you just have to understand and see opinions for what they are: disagreements about ideas," Barrett said of the dissents. "I intend my opinions to be about the ideas, not about the people, and I think a big part of life is assuming the best of other people."

Barrett doesn't seem like a person who dwells in regret. But she said she saw a "missed opportunity" on her cross-country book tour, and she wished she'd emphasized how the emergency orders in the Trump cases are different. Always a teacher, she wants to explain these orders aren't the last word.

"I don't think the public is really aware this isn't the final decision. If a district court enters a preliminary injunction, and we enter a stay of that preliminary injunction, it's not saying the administration wins," she says. "It's simply saying that the administration…can continue to pursue whatever policy it is, because it has not been finally decided yet."

In other words, she says, these interim orders — whether they're allowing Mr. Trump to cut grants or foreign aid or fire political appointees from federal agencies — are short-term, preliminary decisions. The Court is allowing Mr. Trump to pursue those policies for now, but if he ultimately loses on the underlying merits, the aid money will have to be spent and the employees reinstated with back pay.

And Mr. Trump, I said, may not win them all?

"Right," Barrett said.

It may look different, I asked, once you're deciding the merits?

"100 percent," she said.

For now, one factor weighing in Mr. Trump's favor is the Court's assessment of the harm caused when unelected judges reflexively block policies enacted by popularly elected representatives. Because litigation can take years to resolve, those policies may never end up taking effect. The harm caused by judicial interference, the Court has explained, is to the democratic process.

"The case that we always cite is Maryland v. King, and it points out that any time a policy of one of the politically accountable branches or politically accountable state legislatures or governor is stopped, that, in itself, is an irreparable harm because you are affecting the people," she says. "It was the people's preferred policy. The president is the one that they elected. The members of whatever legislature, state or Congress, are the ones that people elected."

"I may disagree, or agree, with whatever choices the people have made in the selection of their representatives," she said. "But the people have made this choice."

Beyond the obvious strain on the Court, the unprecedented crush of emergency appeals also has put pressure on lower court judges, and some have complained publicly that the Court's brief orders aren't giving them enough guidance. But Barrett, always methodical, says more guidance at the preliminary stage would come at a cost, raising the risk of locking the Court into its views before it has fully considered the issues.

"I do think opinions are important," she says. "I don't know that it's always valuable to have an interim opinion that comes before the final opinion."

Barrett, like all the justices when speaking in public, is exceedingly careful with her words. She won't discuss any upcoming issues or cases, or give any hint on how the Court may see the underlying merits. Even her book tour seemed like an exercise in not making news, and she succeeded.

But she will have that opportunity soon enough: The justices already have agreed to decide whether Mr. Trump can impose far-ranging tariffs and fire members of certain federal agencies, including the Federal Reserve Board. In the interim, it's allowing him to pursue tariffs and fire some Biden-appointed commissioners, though not on the Fed. Other cases, including birthright citizenship, are on the horizon.

Beyond the Trump cases, the Court this term also will confront controversial cases on gun rights, voting rights, campaign finance reform and whether students who identify as transgender can play girls sports. The tensions and commentary will not ease anytime soon.

For Barrett, that means staying the course, following her own internal compass and tuning out the noise, because one thing is certain. Whatever the Court decides in any of the cases, she says, "somebody's going to be mad." It's a part of her life now.

"I just think you have to know who you are," she says, "and make decisions that you decide are right, and stick with your priorities and not worry about the feedback you get from others, whether it's negative or whether it's positive."

Jan Crawford is CBS News' chief legal correspondent and a recognized authority on the Supreme Court. Her 2007 book, "Supreme Conflict: The Inside Story of the Struggle for the Control of the United States Supreme Court" (Penguin Press), gained critical acclaim and became an instant New York Times Bestseller.