Vaughn (at left) and Alexander Dawson’s parents struggle to afford their swimming lessons.Credit: Julian Kingma

When Nicolene Dawson migrated to Melbourne from South Africa 10 years ago, she was determined to make sure her children could swim. “I love swimming, I’m an absolute fish,” says the 41-year-old mother of two. “When we came here and were living so close to the beach, it meant swimming lessons were non-negotiable.”

As a stay-at-home mum with a home-based baking business, Dawson had the flexibility to get her eldest son Vaughn, now 11, to weekly mums and bubs lessons. Finding the money to pay the fees was another matter. “We were new to Australia and on a very low income,” she says. “It was rough, but we sacrificed to make it work financially.” But by the time Dawson’s second son, Alexander, was born, life got in the way. Juggling a toddler and a newborn made attending lessons a nightmare, plus Alexander had a string of ear infections. Then COVID-19 hit and swimming lessons were cancelled.

At the same time, Dawson’s business collapsed and her sound-engineer husband, who worked in event management, was made redundant. To make ends meet, she took a full-time factory job while her husband packed computer parts in a warehouse. “It was very humbling,” reflects Dawson, who has a degree in international politics and linguistics. “So then we were two full-time working parents with one child who could swim a bit and another child who couldn’t swim at all. It was the perfect storm of COVID, cost of living and working full-time.”

Dawson’s story is far from unique. It reflects the financial reality for millions of Australian families and highlights an urgent national issue with potentially deadly consequences: swimming lessons, once a rite of passage for Australian children, are fast becoming a luxury only the privileged can afford.

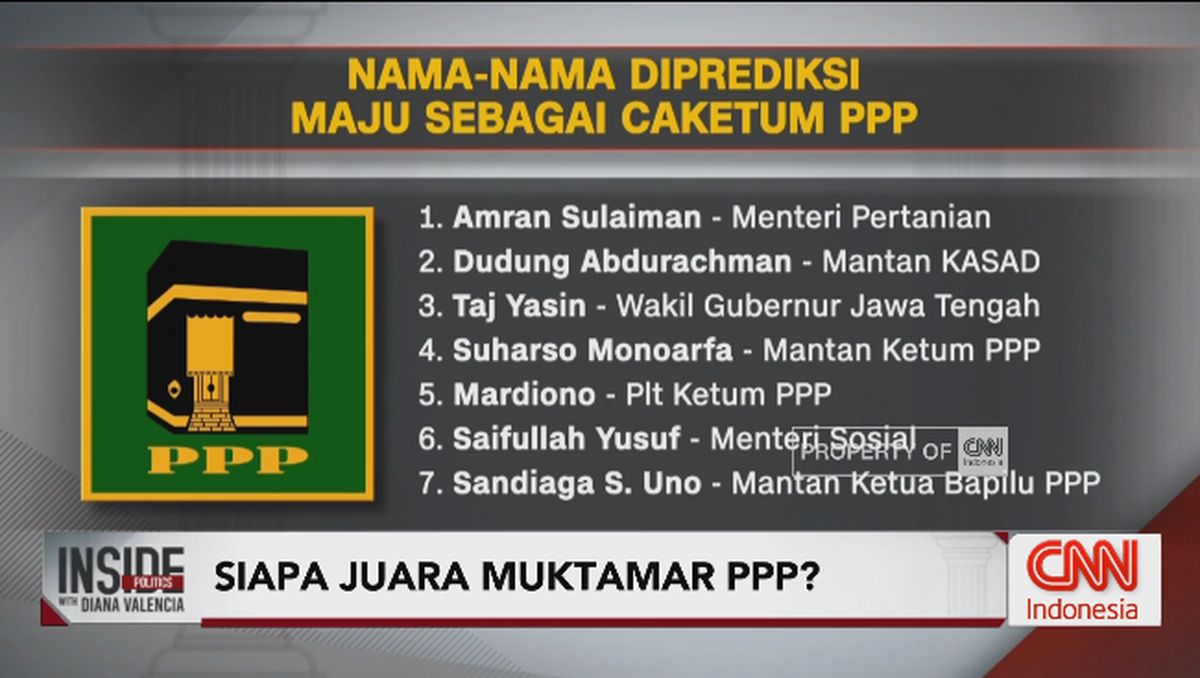

One in four schools no longer hold a swimming carnival due to poor swimming skills.

For the past two decades, Royal Life Saving Australia (RLSA) has been releasing research that paints a bleak picture of a nation that prides itself on its swimming prowess. Research from 2018 estimated that about 40 per cent of children leaving primary school are unable to swim 50 metres, while only 32 per cent could tread water for two minutes – the national benchmarks for swimming and water safety in 12-year-olds.

Post-COVID, children’s swimming and water safety skills have declined further. RLSA research, released in March, surveyed parents and teachers who said almost half of year 6 students couldn’t swim 50 metres. Among high-schoolers, teachers say 39 per cent of year 10 students do not meet the 12-year-old benchmarks, while 84 per cent of 15- to 16-year-olds can’t swim 400 metres and tread water for five minutes – a basic lifesaving requirement and the benchmark for 17-year-olds. The same report found one in four schools no longer hold a swimming carnival due to poor swimming skills.

The pandemic, of course, saw pools closed and a cohort of children miss out on two years of swimming lessons. Many never returned, due to a range of factors including post-COVID waiting lists at swim schools, lack of swimming teachers, cost-of-living pressures, parents working long hours, and pool closures due to ageing infrastructure. Most at risk were Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, migrant and refugee communities, as well as families living in regional, remote and lower socioeconomic areas.

“It’s a big problem, and a multi-faceted one, and there’s not one simple solution,” says Penny Larsen, the RLSA’s long-serving national education manager. Larsen has been at RLSA for two decades, and the latest tranche of data has her seriously worried. She says kids who do not learn to swim in primary school are difficult to coax back to lessons in high school. And while 59 per cent of children start swimming lessons before the age of three, most will stop between seven and nine. “Many families have limited funds,” Larsen says. “We need more funding to ensure children reach national benchmarks.”

Last year, with both herself and her husband working full-time, Nicolene Dawson booked her sons into the only logistically possible and available timeslot: 8.30am Saturday. They managed it for several months, but the weekly grind was exhausting. Saving for – and finally purchasing – their home in Geelong squeezed their budget to its limit. Swimming lessons in Geelong are $18 per child, per week, but Vaughn and Alexander have only attended for a few weeks this year and not at all since March.

While some kids do receive swimming lessons at school, on average, schools allocate 7.5 hours per year to swimming and water safety programs, RLSA research found. And one in three schools do not offer a learn-to-swim program at all, citing cost of lessons and transport, limited staff and a lack of time.

State governments have a variety of learn-to-swim vouchers and programs available, but most are focused on low-income and at-risk communities. In February, the NSW government announced 10 free lessons for at-risk communities to be offered at designated swim schools. Meanwhile, recipients of the means-tested federal family tax benefit receive a $50 kids activity voucher twice a year – half of the $200 they previously received annually. It’s barely a drop in the bucket, with swimming lessons averaging $20 for 30 minutes, higher in some metro areas. Low-income Victorian families receive $200 a year towards sporting activities, and Victoria subsidises a holiday swimming program for kids aged four to 12, with five lessons for $35 over a week.

McKeon’s Swim School director Susie McKeon says it’s the kids “we don’t see at all who we worry about most”.Credit:

The financial burden is falling to parents. “After 10 lessons, some kids are just managing to get their face wet,” says Susie McKeon, whose McKeon’s Swim School in Wollongong, south of Sydney, is one of the designated schools offering 10 free learn-to-swim lessons for Muslim women. “Being able to swim is an ongoing process, it requires lifelong learning.” A former Commonwealth Games swimmer and mother of retired multiple Olympic champion Emma McKeon, Susie McKeon’s swim-school catchment takes in many lower socioeconomic and migrant communities. While she has not seen a drop-off in lesson bookings, and both her locations are wait-listed, she does see families attending lessons for shorter time periods than previously. “With two working parents, it’s incredibly hard to get kids to attend lessons,” she says. “But it’s the kids we don’t see at all who we worry about most.”

The consequences of Australia becoming a nation of weak swimmers are increasingly visible. The National Drowning Report 2025, released last month, found 357 people drowned across Australia in the previous financial year – a 27 per cent increase on the 10-year average and significantly higher than the previous year’s 16 per cent jump. The 2024-25 summer drowning numbers were the highest on record: 104 drowning deaths, an increase of 15 per cent on past years. The 2023-24 summer told the same story: a record 99 drowning deaths, a 10 per cent increase from the previous year, and a 5 per cent increase on the five-year average. Men, children and people from multicultural communities are most at risk.

‘If people are not getting the lessons as kids, then they don’t have the swimming and water-safety skills as adults and they become highly vulnerable to drowning.’

Penny LarsenThere is some good news for children: the lowest drowning rates are among 5- to 14-year-olds. However, drowning rates typically rise for teenagers and young people. Last year, it was a four-fold increase for 15- to 24-year-olds: a total of 44 people drowned, 38 per cent above the 10-year average. Poor swimming skills and risky behaviour are a deadly combination.

Commenting on the new drowning data last month, RLSA chief executive Dr Justin Scarr said the numbers were a “wake-up call” and that the surge in deaths coincided with a decline in swimming skills to the lowest level since the 1970s. Adds Penny Larsen: “If people are not getting the lessons as kids, then they don’t have the swimming and water-safety skills as adults and they become highly vulnerable to drowning.”

Sydney University sports historian Dr Steve Georgakis recalls the moment he became switched on to the importance of learning to swim. He was a student at Birchgrove Public School, in Sydney’s inner west, attending compulsory weekly swimming lessons at the nearby Dawn Fraser Baths at Balmain. “My father was a Greek migrant, and he was amazed,” Georgakis recalls. “He said, ‘What an amazing country this is that it can teach my child to swim.’ ” Georgakis says swimming lessons became mandatory in NSW schools in the 1880s as part of a broader nation-building agenda.

Sports historian Steve Georgakis: “Swimming should be like reading, writing and arithmetic – a fundamental part of growing up in this country,” he says.Credit:

Nearly 150 years on, Georgakis is infuriated that Australia appears to have gone backwards. Access, not funding, is the real issue, he says. “Swimming should be like reading, writing and arithmetic – a fundamental part of growing up in this country.” He goes further, describing the poor swimmer statistics among school-aged children as a “class issue”. “Private schools understand the value of swimming education. They build pools, hire instructors, make it part of the school day. In public schools, we did it better in 1880 than we do in 2025.”

For Georgakis, the answer lies not in pushing for more public funding. Rather, it requires a paradigm shift among educators and policy makers, with swimming treated as a fundamental right, not an optional extra. “Trainee teachers aren’t buying into it,” he says. “Some don’t see swimming as part of their role, others see it as the responsibility of parents. And some think cultural sensitivity means accepting certain groups don’t swim. But that misses the point entirely.” He also argues swimming lessons and annual carnivals should be mandated again in schools nationwide. “Ten lessons won’t make every child a confident swimmer, but it’s enough to shift their fear. It gives them a sense that the pool is a place where they belong.”

Nicolene Dawson’s youngest son, Alexander, is now eight. He completed a week-long, biennial, government-funded, intensive school swim program last year and came out “like a different kid”. Her eldest son, Vaughn, will undergo the same week-long intensive program this year. But one week every second year is a long way from the years of weekly lessons required to swim well and be safe in the water. “Alexander is confident, but he can’t swim,” she says. “That’s dangerous. Kids are braver than they are sensible. They don’t understand how quickly something can go wrong.”

As a middle-income household, the Dawsons don’t qualify for government vouchers. Dawson plans to fast-track Alexander with one-on-one lessons, but that’s a pipe dream for now. “If there was more fat in the budget, I’d do it. But there isn’t. There’s a whole group of families falling through the cracks.”

To read more from Good Weekend magazine, visit our page at The Sydney Morning Herald, The Age and Brisbane Times.