FICTION

Discipline

Randa Abdel-Fattah

UQP, $34.99

In Shakespeare’s Hamlet, the title character speaks of theatre’s purpose to hold a mirror up to nature, reflecting the world back to its audience. This concept has extended to literature over the centuries, and today, novels by Dickens, Orwell, Atwood and more, have been credited for reflecting the times – and their most important lessons – back to us in narrative form.

This is what I thought of as I nodded along to Discipline, the sharp and compelling new novel by multi-award-winning author, former lawyer, academic and commentator Randa Abdel-Fattah.

Though set in May 2021 – when Palestinian families were being forcibly evicted from their homes in the East Jerusalem neighbourhood of Sheikh Jarrah – the novel tellingly encapsulates our intellectualisation of the current Israel-Palestine conflict, as mediated by the two institutions from which our perceptions and understanding flows: the mainstream media and the academy.

It centres on the intersected lives of Ashraf, an academic, and Hannah, a mainstream newspaper journalist, following the arrest of an Islamic high-school student for protesting a university’s ties to an Israeli weapons manufacturer. They are overwhelmed with the weight of world events and the demands on their personal and professional lives, but the arrest is an opportunity for them both: Hannah sees it as a chance to accurately represent community sentiments and experiences without the usual institutional bias; Ashraf sees his personal connection to the school (his former sister-in-law is the principal) as a prospect for government-funded research that will enhance his flailing career.

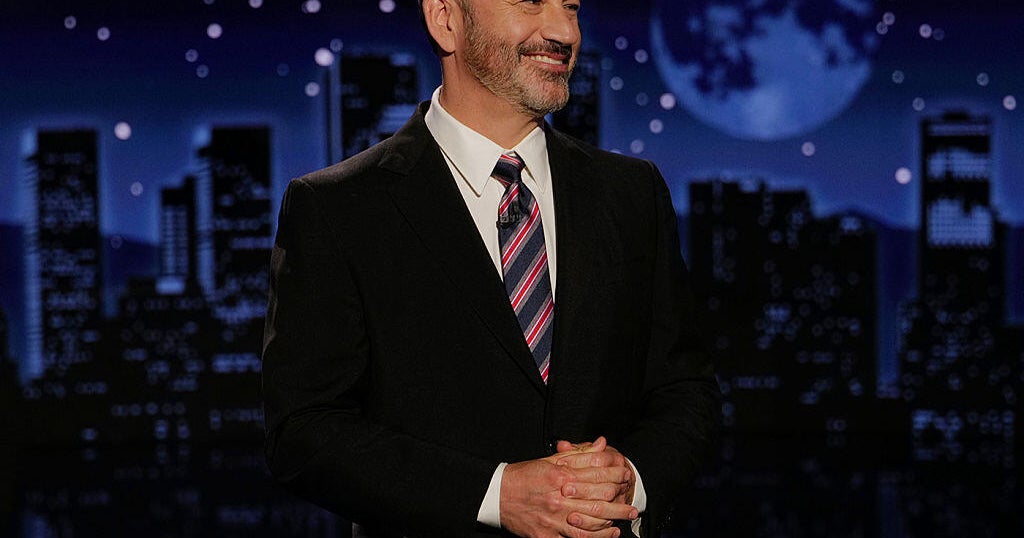

Dr Randa Abdel-Fattah was one of the first authors to withdraw from the Bendigo Writers Festival.Credit: Tom Toby

Ashraf and Hannah are relatable, well-rounded characters. They could be any one of us contemplating our roles in a genocide, crying out for justice or desperate to “find a way to work the system”, knowing it wasn’t designed for all of us. The weight of duty on them is palpable, but they experience it differently: Ashraf is somewhat resigned to the world, grappling with the “dogmatic, purist, single-minded attitude” that he sees as “the death of every Arab and Muslim movement”; Hannah is “wracked with survivor’s guilt” and frustrated by her employer’s belief that her identity makes her “too invested” to do her job with the required neutrality. “If someone says it’s raining and another person says it’s dry,” she reminds him, “it’s not my job to quote them both, [but] to look out of the window and see which is true”.

She laments the chopping and changing of her articles, “washed” and “rinsed” so that their very meanings are changed: the word apartheid deleted, the word occupation put in “scare quotes”, mob violence changed to “clashes”. People who are deliberately killed are portrayed as victims of some random, passive and inexplainable death.

Abdel-Fattah takes both the academy and the mainstream press to task, reminding them of their responsibility to truth and to justice. “Universities are spaces of intellectual challenge and the contest of ideas”, the book reminds us, even as we witness the gatekeeping that tells us otherwise.

And yet, despite its contemplative subject, Discipline is still an engaging story: well-woven, gripping and insightful. Her writing is pointed and matter-of-fact, inviting critical thought and consideration. “Solidarity in the shadows isn’t solidarity,” it tells us. “It’s cowardice.”

Loading

Abdel-Fattah examines intervention and what it might look like, reminds us that “grief is love”, and calls us to maintain hope in the pursuit of justice. Hers is a novel for those wondering how we got here: an overview of “the system” and how it operates, a critique of our complacency, and a reminder that liberation is a collective effort.

Discipline deftly tackles the costs of truth-telling: on painstakingly built careers, on concerns about the future, on communities and relationships, and on our own personal values (and the ability to live with ourselves).

But it is also a novel that holds us all to account: what we will accept, what we will stand for, and ultimately, what we deserve. Are we able to look in the mirror, and see things for what they are? And what will it take for us to do something about it?

Most Viewed in Culture

Loading