Each week, Benjamin Law asks public figures to discuss the subjects we’re told to keep private by getting them to roll a die. The numbers they land on are the topics they’re given. This week he speaks to Marlon Williams. The singer-songwriter, 34, has charted at No. 1 in New Zealand and top 10 in Australia. The making of his latest album, Te Whare Tiwekaweka, was filmed in the documentary Marlon Williams: Nga Ao E Rua – Two Worlds.

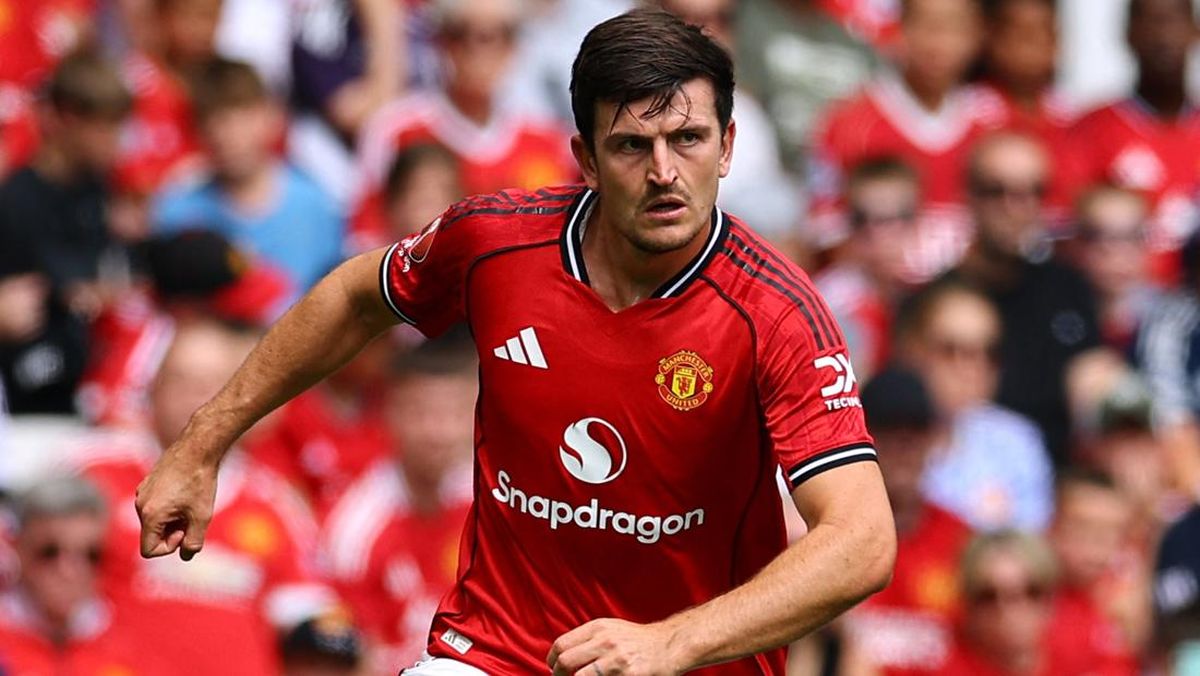

Marlon Williams: “Mum and I always used to sing in Maori.”Credit: Ian Laidlaw

POLITICS

Your new album is the first you’ve recorded entirely in Te Reo Maori. Did you have a mission statement going in? I wanted to normalise it, for it to become a normal part of what I do. Now I’ve done a full Te Reo album, I feel as if I can just play, blend and jump between languages. And, of course, I wanted my family to have something that reflected that part of our culture. You could say that it’s political, but it’s really just family-first.

How does the album reflect your own changing relationship with the language? Growing up, I went to a total immersion [language] preschool. Then I went to a normal school and lost most of it, though Mum and I always used to sing in Maori. Then I had a career writing songs in English, made a few albums and got stuck. This pushed me further into writing [in Maori language]. That broke the seal.

Te Whare Tiwekaweka has come out at a very particular time in New Zealand politics. The Conservative Party has wound back the use of Maori language in the public service and dozens of laws related to the Treaty of Waitangi [which provides a framework for the relationship between the NZ state and indigenous population] are being changed or scrapped. How have you noticed your album sitting in all of this? When there’s a strong push towards indigenous expression, there’s going to be an opposite force of resistance. My hope for this record is that it’s going to be a political album, but it feels more like the court jester …

Oh, how so? It’s aware of the adult politics going on around it, but it’s all singing and waxing lyrical, insinuating [ideas] to the King through metaphor and wit. That’s what music can do.

MONEY

Is it true that you were born in a bathtub? I think I was born on the bed eventually, but my mother was in labour in the bathtub.

What was money like growing up? Pretty thin on the ground. Mum did contract work as an editor for a Maori magazine and illustrations for children’s books, while also painting her own art. My dad played in a punk band but worked at the library. I certainly didn’t go hungry, but there wasn’t heaps going on financially. Both of them were pretty dysfunctional with money, especially Dad. He was on benefits for a long time after he quit the library, but all of his money would go on buying nice things for me. I was the first person at school to have an iPod Touch. They split when I was six.

Were there things you missed out on? For a long time, we didn’t have a home phone. But it was a town of 3000: people just came and knocked on the door. We always had good food. Mum was a bit of a ’90s health-food woman, so we’d be eating organic food and she cooked great things. Dad was a little bit more of a pork bone-soup kind of vibe, which is really on trend now.

What’s your relationship with money like now? I’ve always had that sort of boom-bust relationship with money.

What does that look like? I’m really terrible with money. A boom looks as if I’m spending as if there’s no bottom to my bank account. A bust is when someone in my team pulls me up and says, “You’re spending absolutely insanely.”

Do you have a particular vice? I love to shout people big dinners. Good to do, but it costs a lot. Especially if your friends are oyster eaters.

So I give you a hundred bucks and you have to spend it on yourself in the next hour: what are you going to buy? A massage. I know what a hundred bucks is good for.

RELIGION

Were you raised religious? Dad was Seventh-day Adventist and Mum nothing at all. One year, I got sent away to this school camp where I came back, with a Bible under my arm, singing Bible stories. Mum was furious. She hadn’t been told that it was a Christian camp. I remember her and my grandmother arguing. Mum was saying that I should throw away the Bible and my nana’s like, “Just let him read the Bible.”

How old were you? About 11.

It’s an impressionable age. And they’ve got a lot of catchy songs. They really do. Then I joined the Catholic cathedral choir through my music teacher at high school, who was one of my biggest influences.

What were you singing? Latin stuff, Mozart, Gregorian chants, all the way to 20th-century 18-part Masses.

Wow. The Catholics do pageantry well, right? Totally. I really loved being in church every Sunday of my teens.

Loading

Were you a believer or there just for the singing? Just for the singing. But the lines get so blurred. Now, I’m agnostic.

Why? To me, agnostic literally means not having enough information. Knowing isn’t something that’s afforded to me right now. Atheism feels like doubling down. With agnosticism, you live with a mystery.

Most Viewed in National

Loading