On April 1, just before midnight, as a 2.1-metre king tide smashed the NSW coastline, real estate agent and father-to-be Steve Psomadelis got up for a drink of water. Underneath the floorboards of his low-set 1950s brick house at Dolls Point, on the southern reaches of Sydney’s Botany Bay, he could hear the sound of gushing water. The tide had breached the seawall protecting the foreshore, inundating the waterfront promenade, main roadway and beachfront houses.

At the Psomadelises’ house, a block back from the beach, water was seeping into the laundry and lapping at the sunroom doors. In the driveway, the bonnet of his wife’s car was underwater. “I called out to my wife, ‘We’re flooding,’ ” Psomadelis recalls. Minutes later, seawater was swirling above the top step. Just as Psomadelis and his pregnant wife Stephanie were attempting to climb out a side window, the SES arrived to evacuate them. “We grabbed the cat and got out of there,” Psomadelis says. His street flooded to knee-height, along with the beachfront strip and two neighbouring streets. Water rose through the floorboards of their house, and sand was dumped across their front yard. They lost two fridges and a couch, and Stephanie’s car was a write-off.

Between rising sea levels and more frequent extreme-weather events, Australia’s coastlines are being battered by the very visible effects of climate change. Has the dream of living by the beach become a nightmare? And what will Australia’s coastlines look like in decades to come? “The April king tide was a once-in-50-year event, and it’s happened twice in the last 10 years,” says Psomadelis, who bought his house in 2022, seven years after Dolls Point last flooded in the April 2015 king tide. His neighbours – some who have lived there for decades – also blame infrastructure interventions on Botany Bay including two airport runways and a desalination plant, which they say have changed tidal patterns. “Is it worth it? Yeah, for a place like this, it is,” says Psomadelis. “I can see the beach, and it’s a beautiful area. We won’t leave over something like this.”

The Psomadelises’ house, a block back from Botany Bay, flooded in this year’s king tide.Credit: Courtesy of Steve Psomadelises

Only just the beginning

The bad news for Australia’s coast-loving communities is that rising sea levels are leading to more frequent and extreme events, resulting in severe coastal erosion and inundation of low-lying areas. The drivers behind coastal erosion are complex: tidal patterns, storm systems, ocean temperatures and broader climate cycles like El Niño and La Niña. But rising sea levels complicate the picture further.

The recent east coast low, described by meteorologists as a “bomb cyclone”, and the first to hit the NSW coast since 2022, has brought the topic into sharp focus. It’s likely to cause coastal erosion and damage to infrastructure between Seal Rocks and the NSW-Victorian border. UNSW coastal erosion expert Associate Professor Mitchell Harley says there’s no evidence that east coast lows have become more frequent or severe in recent years. However, rising sea levels means their impact on the built coastline will be more profound. East coast lows are the subject of ongoing research, says Harley, as present climate models lack the resolution to truly capture their unpredictable behaviour.

Sea levels have been on an upward trajectory since records were first collected in the 1880s. But satellite monitoring over the past three decades shows a clear pattern: not only are sea levels rising, the rate is accelerating. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) sixth report, published in 2021, found a global mean sea level rise per year of 3.2 millimetres from 1993 to 2015, and 3.6 millimetres between 2006 and 2015. A 2024 NASA analysis of satellite data found a faster than expected rise last year alone, largely due to thermal expansion of seawater. Scientists had anticipated an increase of 4.3 millimetres but instead recorded 5.9 millimetres – a direct result of 2024 being the hottest year on record. Though these increments sound minuscule, the impact on coastal communities can be monumental. “As a general rule of thumb, for every 10 centimetres of sea level rise, you might see three times more extreme flooding events, depending on your location,” says Dr Julian O’Grady, a sea level scientist with the CSIRO.

The IPCC’s projections for sea level rise are sobering. They vary depending on location and whether we can meet Paris Agreement emissions targets. Even if global warming is limited to 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels, the IPCC is predicting global sea level rises of 0.15-0.23 metres by 2050. By 2100, under very high emission scenarios, it could be 1 metre. Extreme sea level events that occurred once per century will be 20 to 30 times more frequent by 2050, the IPCC says. Along the NSW coast, state government data predicts rises of up to 2.3 metres by 2100 and 5.5 metres by 2150 under very high emissions – figures which, unlike the IPCC’s, include the impact of melting ice sheets.

CSIRO modelling for Melbourne’s Port Phillip Bay, released in 2024, predicts council areas like Hobsons Bay, Greater Geelong, Frankston and Mornington Peninsula could see three times the current degree of sea level inundation under a scenario in which sea levels rise by 1.4 metres by 2100. Add king tides, extreme weather and storm surges, and it’s a disastrous picture for anyone living within a few blocks of a beach.

O’Grady knows just how vulnerable Australia’s coastline is, both as a scientist and as a beach lover. His family camps each year at Pambula Beach on the NSW South Coast. Several decades ago, a storm eroded the front row of campsites. The local community restored a wide, vegetated dune – a natural barrier that now protects the campsite and caravan park. “My kids hear the story every year,” says O’Grady, who explains to them that regular tides and even king tides are highly predictable. But it’s the forces caused by anthropogenic (human-caused) climate change – leading to heavier rain events, more intense cyclones and rising sea levels caused by glacial melting and thermal expansion – that are pushing ocean water further onto land and increasing the potential for coastal erosion.

O’Grady and his team are tracking how often these events occur, how high sea levels rise during them and how climate change is increasing their frequency and intensity, and providing web-based tools and data for local councils. “The coastal councils are doing a great deal to understand and adapt,” he says. “But we need to keep providing information about climate change and sea level rise and how that might impact the coast.”

Residents funded a controversial $17 million sea wall at Sydney’s Collaroy-Narrabeen to protect property.Credit: James Alcock/SMH 2022

Coastal hotspots

Environmental scientists now favour natural strategies to lessen wave impact and slow coastal erosion. This includes beach nourishment, dune revegetation, retrofitting existing sea walls with more vegetation cover or, in some cases, creating artificial reefs offshore. In many local council areas, beach nourishment programs have been underway for years. On the Gold Coast, dredging ships suck up seafloor sediment and pump it back into surf zones, reinforcing dunes and widening the beach. “During Cyclone Alfred, that extra sand made a real difference,” O’Grady says. “But what works in one place won’t necessarily work somewhere else. Where nature-based solutions are not possible, protecting people’s homes, businesses and infrastructure might require sea walls.”

Mention sea walls on Sydney’s northern beaches and you might have to swim for cover. In June 2016, Collaroy-Narrabeen beach became an epicentre of coastal erosion after a violent East Coast low lashed the NSW coastline and stripped the region’s beaches of sand. A home swimming pool teetering above the dunes at Collaroy made global news. In response, residents funded a $17 million, seven-metre-high concrete sea wall to protect their multimillion-dollar beachfront properties. State and local government tipped in $3.5 million. Furious locals, worried about beach access and accelerated erosion, protested, forming a human “line in the sand”.

Expect to see more sea walls in targeted locations around Australia. Recent satellite imagery confirms that erosion is emerging not as a broad, sweeping pattern, but concentrated in known hotspots – especially around tidal inlets, hard structures and headlands where the coastline is more dynamic. In NSW, places such as Collaroy-Narrabeen, Cronulla and Palm Beach in Sydney; Wamberal Beach and The Entrance on the NSW Central Coast; and at Port Stephens, Yamba and Byron Bay further north. In Victoria, hotspots already showing accelerated change include Inverloch on the Bass Coast, Silverleaves on Port Phillip Island, and Apollo Bay and Port Fairy on the Great Ocean Road.

Loading

Inverloch, which is exposed to Bass Strait swells, has lost about two metres of beach per year since the 1990s, according to satellite imagery. Beach loss has accelerated since 2010, with scientists and locals describing it as “significant”. A resilience plan, begun by the Victorian government in 2021 and released in draft form for comment in late 2024, recommends a range of solutions linked to specific environmental triggers. For now, it proposes “adaptation” (dune restoration and beach nourishment) and “accommodation” (lifting, upgrading or reinforcing houses, buildings and infrastructure). A sea level rise of 0.2 metres by 2040, or one of six specific triggers, would prompt “major project engineering” such as seawalls, groynes or breakwaters, followed by “retreat” at 0.5 metres by 2070 – decommissioning buildings and relocating homes. Locals say two triggers have already been met, and they’ve watched the water creep higher year after year. They’re worried there’s still no plan for a sea wall and no talk of house buybacks.

Inverloch SLSC president Glenn Arnold calls the Victorian coastal club the “canary in the coalmine”.

“It’s just money going down the drain, pushing sand around the beach,” says Inverloch Surf Life Saving Club president Glenn Arnold. The surf club, perched atop a beach dune on the ocean side of the road, was sandbagged six years ago. Those sandbags are now failing, with large swells in recent months forcing Bass Coast Shire Council to undertake urgent sand re-nourishment works. The club is the “canary in the coalmine”, says Arnold – and behind it lies several streets of oceanfront homes. “No one is panic-selling yet but in the past, there was a degree of complacency,” Arnold says. “People were thinking, ‘Surely no council, no state government is going to let 300 to 400 houses sink into the ocean.’ Now they want their voice heard. People’s homes are at risk when they don’t need to be. It’s a simple fix, it just takes political will and money.”

Allison and Kim White, both 68, bought their beach house in Inverloch’s Lohr Avenue in 2012 and have lived there full-time since COVID-19. Just one block from the beach, they’ve had a front-row seat to the ocean’s relentless advance. “We used to walk over three sand dunes to get to the water,” says Kim. “Now we walk over one-and-a-half. We can see the ocean from the road now. Before we couldn’t.”

The Whites worry about young families with large mortgages who are anxious that house prices will plummet. For retirees like themselves, the financial threat is also confronting. “Regardless of whether you are living here full-time or whether you own a beach house, the impact is the same,” Allison says. “It’s a huge investment. For a lot of retirees, it’s their last hurrah, their entire nest egg – all they have for their old age, their aged care and to leave their children.”

Inverloch surf club on the Victorian Bass Coast – with homes visible behind – in 2019, before it was sandbagged to safeguard it from dune erosion.Credit: Justin McManus

The Whites say Inverloch’s coastal erosion problem is well known to state politicians, but the urgency has not yet penetrated either political or public consciousness. They are concerned that there are no permanent engineering works planned – just more sand. For a potential funding solution, they point to Western Australia’s Royalties for Regions program, where coastal towns like Esperance, Denmark and Geraldton have received direct, targeted investment. “They’re talking the talk, but they’re not walking the walk,” Allison says of the Victorian state government. “It’s happening before our eyes, and it’s been happening for a long time. What is the cut-off point?”

It’s a question the Whites can’t bear to ask themselves. In their minds, they tally the collective value of homes at immediate risk – about 200 homes worth roughly $1 million each – plus the town’s sewerage system, a caravan park and the RACV Club Resort. If the coast road is breached, the town will be cut off from Cape Paterson and the RACV resort, which is a major employer in the town, and vital infrastructure will be destroyed. The thought is overwhelming – for everyone. “We have not looked at an alternative, it’s too depressing,” says Allison. “At our stage of life, we’re not ready for a retirement village. And I doubt whether any compensation you get back would be worth what you put in.”

The long view

The IPCC says coastal communities must take a long-term approach – 100 years and beyond – to best respond to rising sea-water levels. It ranks beach nourishment as one of the least effective strategies – effective for around 15 years. Elevating houses keeps seas at bay for 30 years. Levees and sea walls work for about 50 and 100 years respectively. “Planned relocation” is the most effective long-term solution of all.

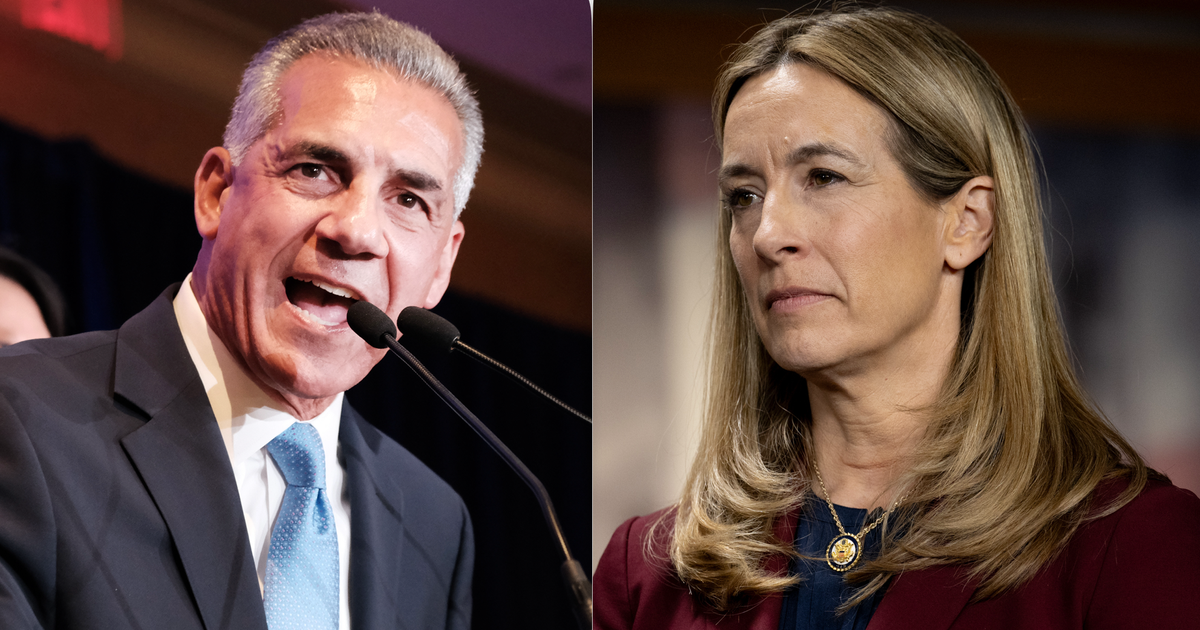

For someone who’s studied his field for more than 20 years, coastal erosion expert Dr Mitchell Harley didn’t start out as a beach lover. “I was born and raised on Sydney’s northern beaches, but I wasn’t your typical beach kid,” says Harley. His passion for maths and science led him to a degree in environmental engineering, and later, a PhD – one that saw him driving a quad bike up and down Narrabeen beach every month for years, collecting data. “It sounded like a good gig,” he laughs. “And that’s how I ended up studying coastlines.”

Coastline expert Dr Mitchell Harley wants councils to allow building only in zones that are safe from erosion.

Harley is one of Australia’s leading coastal researchers. He names the June 2016 East Coast low, which stripped sand from Collaroy-Narrabeen and other NSW beaches, as one of the most memorable events of his career. It was a moment that captured for him just how vulnerable Australia’s built coastline is. “I knew that beach [Narrabeen] like the back of my hand – and suddenly, it was unrecognisable. Just gone, overnight.”

Harley’s research suggests that not all beaches will suffer equally. Some may look unchanged, while others could shrink rapidly or disappear altogether. In remote parts of the country, where there is little housing or infrastructure, beaches will migrate and we won’t even notice. The real issue? Planning decisions made a century ago, and in the decades since.

Loading

“Places like Collaroy and Narrabeen were zoned too close to the coast back in the early 1900s,” he says. “We’re still paying for those decisions 120 years later. But what really concerns me now is that we’re making similar mistakes.” Harley and his team work like storm-chasers, deploying technology and aircraft to scan all Australia’s 11,000 beaches before and after extreme weather events. One of their most powerful tools is CoastSnap, a citizen science initiative where people use their smartphones to photograph beaches. Harley collates the photographs to measure and track beach erosion over time.

But good data won’t be enough without strong planning policy and funding, he warns. His research aims to identify coastal setback lines – “basically the line in front of which you shouldn’t be building”, he says. He wants to see all tiers of government maintain the dynamic coast and only build in zones which are safe from erosion. “Beaches act as natural buffers,” he says. “If we lose that, the waves will break right against sea walls and promenades. It’ll be more hazardous, more expensive to manage and much less accessible.”

So what will Australian beaches look like in 2050 or 2100? “Some beaches will look relatively similar to what they are today,” Harley predicts. “Others will change. Some urban beaches will have very little sand and we’ll be climbing off staircases, straight into the water. We’re going to lose access in some places because the beach will be more hazardous. For many parts of the country, it’s likely that the sand beaches that we know today will no longer exist, without expensive interventions.”

Harley points to Manly’s Fairy Bower. A 1956 painting held in the State Library of NSW depicts a small sandy beach, tucked in against the curve of the roadway. Today, it’s a rocky platform with a tidal pool protected by a small sea wall. “We’ll have to learn to enjoy our beaches in different ways,” he says.

To read more from Good Weekend magazine, visit our page at The Sydney Morning Herald, The Age and Brisbane Times.