Let’s begin this murder story with a confession. I spent years being completely anti-Jane Harper. In a short-lived book club I was once

a part of, we selected her fourth novel, The Survivors, to discuss. This book was an instant international bestseller; The New York Times praised its “complicated, elegant web” of secrets; recently it’s been released as a globally successful Netflix series. But apparently I knew better than the reading and viewing audience of the entire world, because I was immediately filled with secret book club rage over our choice, and refused to read it (which means I either faked it at book club or didn’t go that month – mercifully I can’t remember which). I had not read any of Harper’s three preceding novels – The Dry, Force of Nature or The Lost Man – and I did not read her fifth, Exiles. Even when I wrote a story about, in part, the filming of Force of Nature: The Dry 2 (for which I interviewed the director, and the producer, and Eric Bana, and attended the premiere), I still didn’t read the book on which it was based.

What on earth was I thinking? Before I interviewed Jane Harper for this story I read every one of her novels, including her most recent, Last One Out, published this month. And all I can say now is, I’m ashamed of myself.

‘Few people do what she does’

The details of 45-year-old Jane Harper’s life before she was hit by the juggernaut of fame are well known. How, after more than a decade as an unobtrusive newspaper journalist in the UK and regional Victoria, she signed up for an online novel-writing course and began working, quietly and methodically, on the storyline which became The Dry. How the manuscript won the Victorian Premier’s Award before it was even published, was auctioned to Pan Macmillan on the day of her wedding and swiftly became a global sensation. How it was translated into more than 35 languages, sold more than a million copies and won awards all over the world, including a Book of the Year gong at both the British Book Awards and the Australian Book Industry Awards, not to mention spawning a movie which became one of the highest-grossing Australian films of all time. How her subsequent books have also been bestsellers – her total sales now top 3.5 million – and there’s been a second movie (Force of Nature), the Netflix series, and an option on The Lost Man. And how her life, as a result, has changed beyond all recognition.

She herself, however, seems not to have changed at all. When she opens the door to her comfortable old Californian bungalow in Melbourne’s Elwood (which is itself new since The Dry; she used to live in an apartment in St Kilda), she looks exactly the same as she does in photos from nine years ago: small, red-haired, corkscrew curls in a half-ponytail. Despite her turquoise top and casual pants, she has an appealingly old-fashioned face, like a character in a British costume drama – an impression aided by the remnant of a northern English burr in her voice. It’s a friendly, determined face: you could imagine her gossiping over a vicarage gate in a picturesque English village or leading a band of militant suffragettes into Hyde Park.

Harper’s 2015 wedding with Pete Strachan, held the same day that Pan Macmillan bid for The Dry.Credit: Eugene Hyland

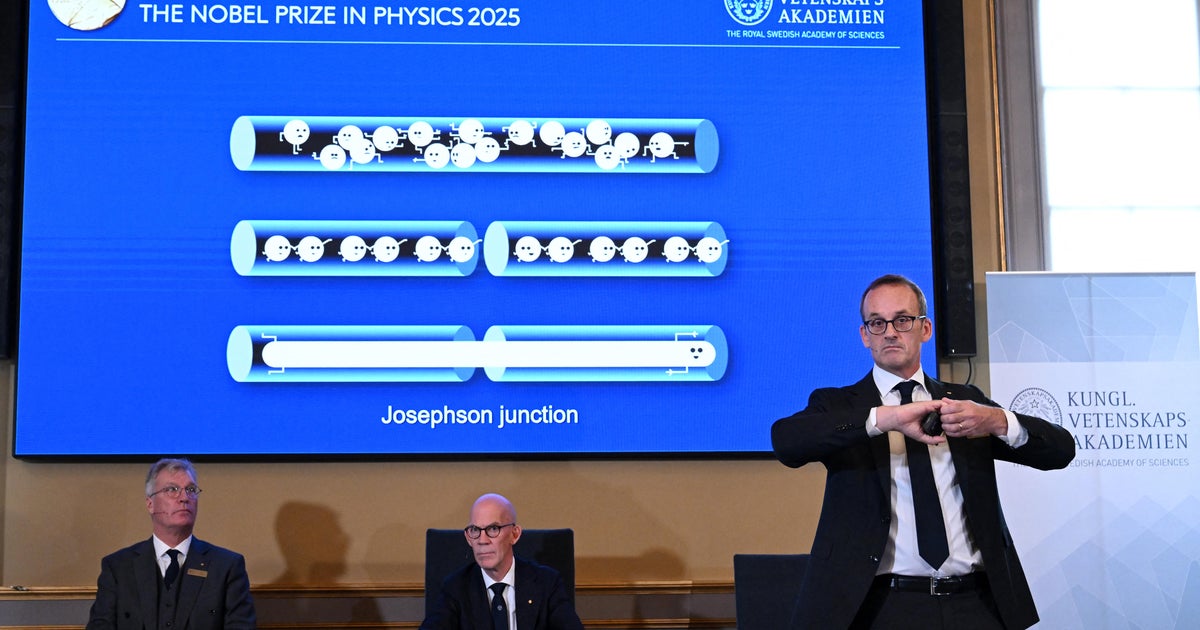

“She really hasn’t changed,” confirms her husband Pete Strachan, a dark-haired man in glasses (also an ex-journalist, now a web developer), who – along with the two cats of the house – appears alongside Harper in the hall. He’s a quiet, friendly-seeming man: when I talk to him later, he sounds surprised to imagine that global fame and fortune might have had any impact on his wife. “I mean, it’s true, you might think so, right?” he agrees. “But no. Her values are exactly the same as they’ve always been. She cares about all the same things.”

After introducing Strachan and the cats, Jane leads the way down a dim, cool corridor – pale walls, dark floorboards – to a staircase. I’ve asked to see her writing room, which is at the top of the house, and as we climb, we pass a series of enormous black-framed posters of her book covers, carefully positioned in chronological order. “Pete did this,” she acknowledges cheerfully.

There are few people who are capable of leading you up a staircase lined with four-foot-high glossy images of their own novels, past an alcove featuring several award trophies and into a room with a bookshelf containing their own words in multiple languages, and still not seem remotely like they’re showing off. Harper, apparently, is one. “Is this one Japanese?” she guesses, pulling out an edition with a cover of a shadowy figure who appears to be forest-bathing in a snowstorm. “No, hang on, that’s Korean.” She pulls out another one. “This is definitely, um, maybe Hungarian?”

These books demonstrate, as well as anything in Harper’s low-key orbit can, the sheer enormity of her global achievement. It’s hard to remember when you meet her but, measured by both her sales and her critical reputation, today she is one of the top crime writers working anywhere in the world. Her writing is recognised globally for what her Australian editor Claire Craig calls “its intensity of character; its slow but inexorable creep of menace”. Her success has been so great it has spread beyond her own novels, creating a demand that’s spawned an entirely new sub-genre of crime writing, outback noir, now filled with other international Australian success stories such as Chris Hammer (of Scrublands fame), Candice Fox and Margaret Hickey.

‘As an editor, you just sit back and enjoy it … Every nut and bolt is in place. It’s a masterclass.’

Claire Craig“What Jane does is an incredibly hard, unusual thing to do,” explains her UK editor, Alex Saunders. “She’s able to marry tight structure, compelling plot, great characters – all the things you get from really great crime fiction – alongside this immersive setting, and this unique emotional intelligence. Very few people can do what she does.”

“[The ingredients to a great crime novel are] very hard to balance,” agrees her US editor, Christine Kopprasch. (In more than 20 years, Harper is the only novelist I’ve ever interviewed working with three editors, on three continents, simultaneously.) “She’s taking all these familiar crime tropes and doing them at such a high level. She is just a major talent.”

“As an editor, you just sit back and enjoy it,” concludes Claire Craig, describing the moment when the manuscript for Harper’s latest novel, Last One Out, arrived in her inbox earlier this year. “Every nut and bolt is in place. It’s a masterclass.”

A room of one’s own

So. How do you transform yourself from a successful first-time author into a world-wide crime fiction powerhouse, still going from strength to strength after a decade? Well, if you’re Jane Harper, you have two children in quick succession, write your next five novels through the hellish fog of early parenting (her younger child, Ted, is still only five) and take quite a long time to secure yourself either a dedicated writing space or an organised writing plan.

The room at the top of the house is Harper’s answer to the first issue. It’s sparse and efficient: grey rug; desk with a computer; chair; bookshelf; chest of drawers and a printer. The only touches of colour are an excellent framed jellyfish drawing by Harper’s nine-year-old daughter Charlotte on the bookshelf and a wildly bright mat under her keyboard. “I think that’s to cheer me up,” she says of the mat. “On a hard day, I can look down and think, ‘OK, maybe things aren’t so bad.’ ”

Harper seems – as she does about many things – pretty matter-of-fact about this room. There’s no talk of inspiration or Woolfian creative independence. It’s useful to have somewhere to go, she admits – before this she rented an office space, and occasionally worked at the local library – but she doesn’t seem to love being up here, especially when her children are home. “I tend to work around their schedules,” she says. “I don’t shut myself away or stop them coming in. To be honest, I mostly don’t work when they’re around.”

This privilege – that of being a mum with her kids in all their after-school, witching-hour glory – is the crazy, but also believable thing that Harper loves most about being a publishing multimillionaire. “I remember the hours I used to work,” she says. “I can imagine how much beforecare and aftercare they’d have if I was still at the newspaper. So the absolute of luxury of not working on school holidays; not working on weekends – that time is really, really valuable. I treasure it.”

Loading

When her children aren’t around, however, Harper is a demon of efficiency. Leading the way into a bright living room containing an immaculate cat-scratching post, two heavily cat-scratched sofas and an avenue of Dubai-style Lego constructions, Harper sits down on a squashy couch. The fact is, she says, she always wanted to be a novelist. “Honestly? Probably since I was a child. It was kind of my secret burning ambition. Becoming a journalist seemed like a step towards that, and it was a way of getting paid to write. Because I had very little confidence in my skills, even with journalism. But I did my training courses and things, so I knew I could write news stories. But a novel seemed like such a mountain to climb. I just couldn’t imagine how anyone did it, you know?”

With The Dry, one gets the sense Harper did it by sheer force of will: an hour at the kitchen table before work every day, an hour after work. “I kind of thought, ‘If I keep on doing this for as long as I can stand it, to be honest, eventually it will reach a standard where probably it will be workable.’ ” And then suddenly – far more suddenly than she ever expected – it happened: her novel was published, it was a huge hit, and she had to repeat it. “And I had to think, ‘Well how exactly did I do that? Let’s try and really work out how it happened, and how to do it again.’ ”

The answer, for Harper, was planning. “Planning, planning, planning,” she agrees, sitting forward. “It took a few novels, but I’ve kind of got it down now. So, with this last book, for instance. I start with a skeleton – maybe one page. And quite often I start from the end point: the murder itself. Who did it, how did it happen, what brought the characters to this extreme moment? And then I literally just expand it out.” This expansion can be enormous – up to 35,000 words – before she starts on the actual novel itself, which she writes straight through, from beginning to end. “But by then, I might have mapped out a lot of the scenes, whole stretches of dialogue; I know they’re going to have this conversation in a cafe; I know they’re driving home and that’s when so and so says, ‘You’ve always liked hunting knives’ or whatever; this is where I’m dropping a clue in. I like to keep track of what the characters know at certain points; what the reader knows.” She grins. “Or what the reader thinks they know.”

“I’m dropping a clue in. I like to keep track of what the characters know at certain points; what the reader knows.” She grins. “Or what the reader thinks they know.”Credit: Kristoffer Paulsen

One of the cats appears in the sitting room, ignores the scratching post and vigorously attacks the sofa. Then, after a disdainful sniff at me, she arranges herself carefully on Harper’s crossed legs. Harper holds her in place as she speaks. “The planning helped me realise how to just take it literally one step at a time,” she reflects. “You don’t have to know every single thing that’s going to happen. You can just write down things you do know, then fill in some gaps, just keep working away.”

It’s an important part of Harper’s modesty that she really believes this: really believes that you can write a great novel just by taking things calmly, and not being too hard on yourself, and getting organised. In fact, she takes it so seriously she’s even done a TED Talk, replete with suggestions about time management and word documents.

“I’ve watched that TED Talk!” laughs Sally Hepworth, a near neighbour and close friend of Harper, who is herself a bestselling author: the pair met when they were both pregnant (third and first babies respectively) and publicising novels (second and first). “Whenever I get asked a question about writing a novel, I always say, ‘Go and watch Jane.’ She’s so good, and it’s so unusual for such a successful writer to do a ‘how to’ like that. But that’s classic Jane. Matter-of-fact and really, genuinely kind.”

Harper brushes this off. “I don’t want people to get demoralised and give up,” is how she puts it: “I remember how hard it is when the only comparison you have is with published books, which have been through multiple drafts and editing and everything. Whereas I’m lucky: I can go back and look at my early drafts, and say to myself, ‘Look, look how bad this was at the start!’ ”

It’s worth saying that nobody sees these drafts but Harper – not her editors, not her friends, not even Strachan; though occasionally, she does ask for his input. “It’s a bit hard for him, because he has no context,” she admits. “Although I do remember when I was writing Exiles, there’s a scene in it where Falk [Harper’s protagonist] and Gemma [Falk’s love interest] first meet, and they’re in a bar. And I showed it to Pete, and I was like, ‘Is it believable that she would have a drink with him, do you think? Have they had enough small talk?’ And of course, this is after the movie came out, with Eric Bana playing Falk. And Pete was like, ‘Well, the good news is that everybody is going to be picturing Eric Bana. So yes, of course she’s going to have a drink with him.’ ”

Eric Bana with author Jane Harper, who created the Aaron Falk series. She has said the third book Exiles will be the last.

Aaron Falk, it must be said, is a surprisingly memorable figure, even without Eric Bana’s input. Jane Harper’s mother, Helen Harper, still hasn’t got over his retirement into bucolic domesticity at the end of Exiles. “I’m sorry Jane’s got rid of him!” she exclaims. “He’s a deep character – he could do with more exploring. Him and snakes. I’m always saying to Jane, ‘Put in more snakes!’ I think they’re terrifying.”

Helen and Mike Harper are lifelong crime fiction fans. Born in Manchester, Jane Harper, her younger brother and her sister all read the same authors as their parents: Patricia Cornwell, Ian Rankin, Val McDermid. “Crime fiction was really our genre of choice as a family,” explains Helen, whose own background was in English language teaching (she was an ESL trainer for Gurkha soldiers), while Mike was a product manager for a computing company who later opened a guitar shop. Both recall Harper as a talented writer, even as a kid. She’d work away on her diary – “which we never read!” – and on stories about everyday dramas: her driver’s licence test; the arrival of an exchange student at school; the odd imaginary murder. Mike remembers her publishing a short story in the UK Big Issue in her late teens or early 20s – “a murder-mystery,” recalls Helen with relish. “And it had an ending I didn’t spot – though generally, with most authors, I do know. So that was a good sign.”

Loading

The family moved to Australia when Harper was eight, and she attended primary school here and learnt how to swim “like an Australian rather than a Brit”, as Helen puts it. This period also first introduced Harper to one of the crucial ingredients to the success of her novels: the Australian landscape. The whole family found the countryside around Melbourne endlessly fascinating. “We lived in [the outer suburb of] Boronia,” recalls Helen. “And we got such a thrill even from the flocks of galahs out there.” On the weekends, after netball or Little Aths, they’d drive out to Anakie, the Dandenongs, Phillip Island, Wilsons Promontory. “We all enjoyed it,” recalls Mike: “I don’t remember any of the kids rolling their eyes.”

When Harper was 14, her family returned to the UK, where she remained until her early 20s. But when she got a job with the Geelong Advertiser in 2008, her parents remember her being “excited and pleased” to come back to Australia. “I think she felt safe here,” says Mike. “It did feel like home.”

Home, but with a twist of the exotic. This is the feeling Harper has co-opted into her novels, the strangely familiar otherness of the Australian bush: the waiting stillness, the eerie beauty balanced on the edge of violent-death danger (even in the absence of snakes). It’s such a powerful ingredient to her stories that when they’ve been put on screen, every one has remained tied to its original setting – despite the cost and inconvenience (filming in 40-degree heat, anyone? Leeches up the nose on set?) “The landscape in these stories is just intoxicating,” Robert Connolly, director of both The Dry and Force of Nature: The Dry 2, told me when I interviewed him in 2023. “All the narrative of these stories is written into the landscape. You can’t untangle one from the other.”

It’s this interdependence that has made Harper the so-called queen of outback noir. Unsurprisingly, she spends a lot of time on international tours answering questions about the Australian bush. “Especially in America, people want to know to what extent is the landscape realistic.” She laughs. “They’re wondering, have I exaggerated for fictional purposes, that kind of thing. Whereas in Australia, I think we recognise the landscape as real. Although I do remember being out at Birdsville when I was researching The Lost Man [my favourite of Harper’s novels] and realising I was actually going to have to tone it down. Not just the landscape, but the tensions, the feuds, stuff where I felt like, ‘No one will believe that.’ The whole thing was just so extreme.”

Harper moved to Australia from England when she was eight.Credit: Courtesy of Jane Harper

The other particularly Australian quality Harper has picked up on her travels is accurate dialogue – accurate Aussie male dialogue, no less. All five Harper novels so far have been narrated from the point of view of men; it’s a marker of her expertise that she’s carried the male voice so naturally for so long; and of her versatility that she’s changing now (Last One Out is narrated by a woman). But once again, Harper’s unimpressed by her own skill. “I just look for the person in the cast of characters whose point of view is most obvious, and sort of makes most sense to tell the story,” she says. “Ro Crowley [the main character of Last One Out] made sense, because of her history with the town and her relationship with her husband and her memory of raising her family there. She was the obvious choice.”

Harper’s characterisation, say reviewers (including multimillion-selling Irish writer Marian Keyes, who is a Harper super-fan and says her “mastery of genre and atmosphere means she transcends genre”) draws the reader close – sometimes disturbingly close. Even the killers are not crazed psychopaths beyond our understanding, but often ordinary people driven to murderous extremes. Editor Alex Saunders recalls reading Last One Out and thinking, “‘What if I was Ro Crowley and my son had gone missing?’ I’m not a mother,” says Saunders – who is, indeed, a man – putting one hand on his chest. “But if I was a mother reading that book, it would really take me there. So Jane is allowing readers to experience terrible things from a kind of remote safety.”

There are, however, things Harper won’t write about. Perhaps since having her own children, she won’t write about child murders [Crowley’s son is 21 when he dies]. “When I think back about the death of Billy Hadley in The Dry, who was six years old, I think it was the right thing for the book,” she admits. “And I mean I never regret a word of that book – it changed my life, I am so grateful to it and I love it and I’m so proud of it. But it was my first novel, and I’ve got more skills now. I never did it again after that book and I can’t see needing to do it again.”

Nor is she interested in mixing her journalistic and novelistic skills in true crime. “I actually quite hate true crime,” she confesses, putting the cat down and uncrossing her legs. The cat, wearing a martyred expression, jumps straight back into her lap. “I don’t listen to any of those podcasts; I don’t read any. It’s the realness,” she says after a moment. “When I was a journalist, you’d go on a door knock” – also known as a death knock, this involves literally knocking on the door of someone who’s just lost a person close to them – “and you see this incident that’s happened in this family and it has changed them forever. The whole spectrum of it is so sad and challenging. And I absolutely do not find it entertaining in any way. I just don’t. I mean, I guess no judgment. People enjoy all kinds of things I don’t enjoy. But it’s not for me.”

Enjoyment, perhaps oddly, is what she most wants everyone to get from her books. “I want them to be really gripping and I want people to feel the pain and all of the kind of emotional journey, but I don’t want it to be too sad,” she grins. “Not so sad they can’t go on. Because reading is supposed to be entertaining and enjoyable. It’s a hobby – you don’t want people to feel they’re being beaten around the head with a really difficult subject. I want people to be able to close the book and get on with their day.”

A dream job

Speaking of getting on with the day: our plan had been to go to a local café for lunch, but by the time we get organised, all the cafes are shut. Unfazed, Harper makes ham and cheese toasties in the kitchen, while I admire her son’s robot (or is it alien?) cardboard box costume by the bench. “Oh yes, he had very specific instructions,” says Harper, whose craft skills seem strong: she and her daughter have also been baking (baking skills less strong: “We made a cake I nearly forgot to take out of the oven, then I cracked it getting it out of the tin. She was quite annoyed at me”) and making scrunchies on a kid’s sewing machine delivered by her sister. “She got it from the op shop,” recalls Harper. “It definitely had an edge of someone having given it as a gift when they weren’t going to be responsible for actually using it – which was, I have to say, not totally unlike my sister giving it to us. But we did make a couple of really great scrunchies, which was incredibly satisfying. And also a Minecraft pillowslip for Ted, which we’re super proud of.”

I have to say, Harper looks every bit as thrilled by these achievements as she does by the delivery of the manuscript for Last One Out, after two years of work, to her three international editors a few months ago. Because she’s Jane Harper and, planning, she’d had the date in her diary all year; it arrived and she sent the manuscript off, absolutely on time. “I went and sat in the spa with a glass of champagne,” she recalls. “Well, actually Coke Zero – it was the middle of the day.” She laughs. “That was a good day.”

It was also a good day for her editors. “Honestly, I’m just reading as a reader the first time,” says Claire Craig. “Just for pleasure. And there’s so little you need to do.” Her international counterparts agree. “[The draft] felt incredibly clean and polished,” says Alex Saunders, “and she’s an incredible professional. Not sensitive, not needing lots of reassurance: she’s always saying, ‘Tell me the truth, don’t sugar-coat it, let’s make it the best book we can.’ ”

Loading

Harper herself says she relishes the editing process. “I always feel a real curiosity about what [the editors] think,” she says. A marker of her confidence, perhaps, is that dealing with all three editors together is not, apparently, wildly intimidating, but intriguing and helpful. “Seeing the areas where they agree or disagree is quite useful,” says Harper. “But if you go into the editing process with an open mind, it always elevates it. And sometimes there are things that you just actually can’t see yourself.”

Maybe she sees me looking sceptical, because she pauses and leans forward. “Honestly,” she says, “this whole thing,” she gestures around her, “is the best job I’ve ever had. I love it. I love seeing the books come together. I really enjoy being with the characters and story. I get to work with some really great people at the publishers, and then the readers are so wonderful and the booksellers as well, and the librarians. I actually get so many people just being so really positive and supportive. It’s so great.”

Harper sits back. So is it true, I ask, that the past nine years have really lived up to your childhood fantasies of what it would be like to write a book? She smiles and nods over her toastie. “It really has, absolutely,” she says. “I genuinely could not ask for more.”

To read more from Good Weekend magazine, visit our page at The Sydney Morning Herald,The Age and Brisbane Times.