By Declan Fry

October 1, 2025 — 12.00am

FICTION/MEMOIR

The Möbius Book

Catherine Lacey

Granta, $36.99

The best book I’ve read this year crept up unannounced. I was just going about my life – and boom, there it was. No introduction. No witchy presentiment. Not even an earth tremor.

Having finished Catherine Lacey’s new novel, I find my world changed. Enlarged, a little. It is inside of me now. Once a good book does that, you can’t go back.

The Mobius Book is composed of two parts. One is fiction, the other is memoir. The reader can choose either entrance. Each half refracts the themes and subjects of its neighbour. Strange correspondences and seemingly incidental connections appear across the two parts: a climactic event at sea. Broken teacups. Violent partners. The effect is akin to telling a story and realising, once you return to the beginning, that there were actually little connections, unknown in advance, all along.

In the fictional half, two friends, Marie and Edie, meet up for drinks. Edie is a parallel avatar of Lacey in the memoir, fleeing from one love toward another.

Edie reports the speech and ideas of her new boyfriend as though they were her own. It’s an unnerving self-transformation: all her opinions conveyed within the parameters of her partner’s, as if he had educated her in a language she might never have otherwise found. There was “nothing anyone could say or do to a woman with that much faith in the fire she was happily setting”, Marie observes.

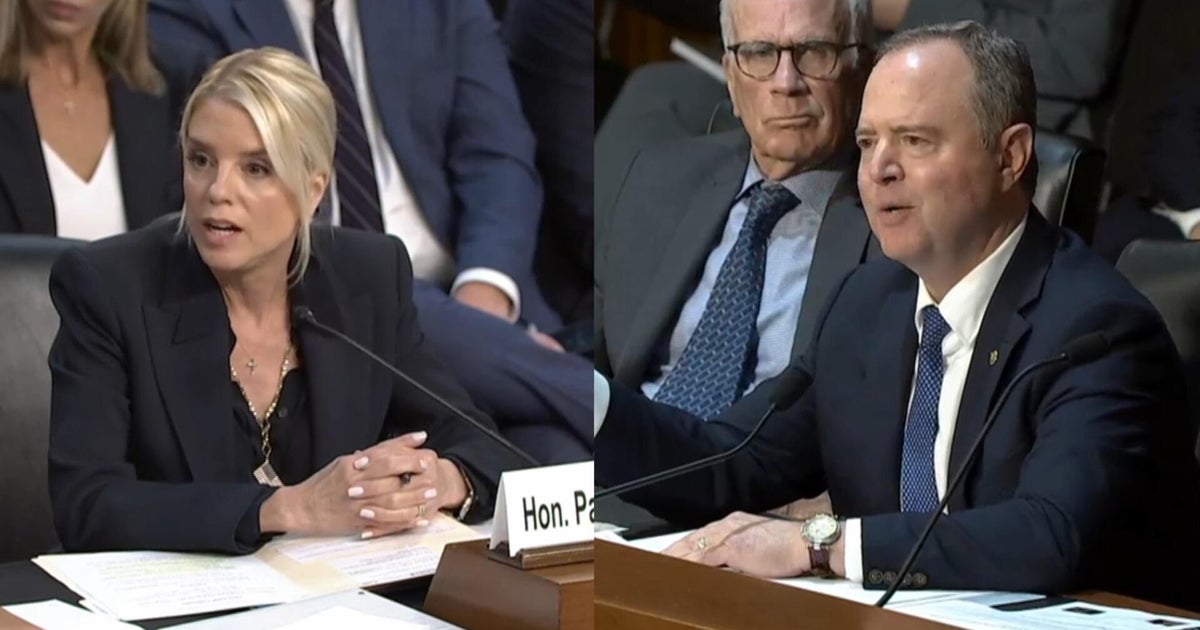

Catherine Lacey’s new hyrbid memoir/novel is a blazing, beautiful achievement.Credit: Daymon Gardner

In the memoir half, Lacey is recovering from the end of her own relationship. Crying jags regularly overtake her. Ordinary words are freighted with existential instruction. (Want to look at the copy on a jar of peanut butter for relationship advice? Go ahead. Separation is natural!)

To make sense of who she now is, she recalls past relationships, her lapsed Christian faith. Once, as a young woman, she starved like a medieval saint, her body an “altar to the Lord”. (One suitor, an androgyne atheist, tells her he is willing to wait forever – and does.) Yet religion waits a long time, too. Lacey finds herself missing “metaphysical certainty” – the riddles solved, “everything in its right place.”

Her self-worth, when she was with her old partner, was tied to his regard. He was protective, violently so, not only toward her but of her. The way he envisaged her became the way she envisaged herself. She wanted to become someone deserving of him, or at least “deserving” of the shapes he made for her to inhabit.

Loading

To be caught within a lover’s spell is to begin to see the possibility it can be broken, Lacey learns. Yet to break his spell is to lose one of the ways in which she has come to know herself. Protection, it seems, can double as possession. Now that the relationship is over, she must seek other reasons for living. (A happy thought: there is time for everything. Its correspondent, a little less joyful: everything has its time.)

Lacey’s memoir is wrenching. Call it a record of distortion: how a life can be made to fit the contours of someone else’s shape, until it is no longer capable of doing so. Deciding what truly belongs to her and what she must dispose of, Lacey grows sceptical. What if we are unable to ever really complete the task of knowing ourselves? What if disposal is an illusion, since nothing goes entirely, just as nothing stays?

The memoir’s gorgeous ending reveals this understanding as akin to the idea of finding and losing language – and, along with it, a particular sense of oneself. Loss is at once a salve and a stricture, something “quite common in disguise as something unforeseen”.

Loading

Lacey’s desire for fiction, as a reader and writer, slowly dissipates. She learns to give herself up in new ways, submitting not to a partner or sacred text but to the unknown. She finds small pockets of time and space where she can relearn what she needs.

The Mobius Book is a pas de deux, a resonant series of reflections on mortality, grief, loss, and the abiding search for what matters. Reading books like this – books you can live inside, that reconnect you to the possibilities of reading – I felt I was freed from the memories or times I had spent trundling a stick through the fences of books I couldn’t live in.

Reaching the last page of Lacey’s memoir, I found myself audibly whispering, F--k, it’s good. A real Neapolitan treat. (Elation! Anger! Joy!) Like love, hers is a delicate, blazing, beautiful achievement. And did I mention it’s extraordinarily funny, too?

I am in awe.

Most Viewed in Culture

Loading