This is the story about Central Australia we don’t hear enough. More than 30 art centres across an area of two million square kilometres that support thousands of artists, going back decades. Not only do we see great work produced in these places, the artists are also generating income for their communities that’s used across an array of social initiatives.”

Curator Hetti Perkins (Arrernte / Kalkadoon) is taking me through the final installation of Desert Mob 2025, the annual exhibition held in Mparntwe / Alice Springs which showcases work from Australia’s vast, diverse desert environments. The galleries in Araluen Arts Centre pulse with colour and movement, from APY Lands’ large, intricate landscapes, and Ernabella Arts’ sturdy elegant pots, to the playful sculptures of Tjanpi Desert Weavers who this year created a sports triptych featuring wild-haired fibre figures playing ball games on woven tjanpi (desert grasses).

The 2025 Desert Mob Marketplace at the Araluen Arts Centre.Credit: Sara Maiorino, courtesy of Desart

Begun in 1991, now run by advocacy organisation Desart, Desert Mob has grown to include an opening night party, artist talks, a marketplace, public programs and satellite events. Drawing from 16 or more language groups, the festival reminds us Australia is a continent of many nations. Desert Mob could therefore more accurately be described as an international gathering at which East Coast urbanites such as myself are foreign guests.

The main exhibition now extends through several large galleries, with satellite events in town at cultural centres such as Purple House. Visitors can engage with the art not only by purchasing works from the literal source, but also by hearing from the artists about their work more broadly.

Coralie Williams with her work, “Sandhill Camp, family’s home, Ntaria” 2025, at Desert Mob 2025. Credit: Sara Maiorino, courtesy of Desart

Over the opening weekend, as artists roll into town from long journeys across rugged country, excitement grows. People are seeing their work hung, sometimes for the first time, catching up with family, meeting peers from distant communities. The centre is abuzz with language, translators in attendance. Many artists are elderly, some sick, in wheelchairs, yet their mere presence is testament to the success of the art centres.

Chief executive Philip Watkins (Larrakia / Arrernte) emphasises: “Often, things every Australian should have – access to health services, to housing, education, good water – don’t exist or are limited in these communities. And often the art centre picks that up.”

Marcus Camphoo Kemarre’s “Untitled 2025”.Credit: Fiona Morrison, courtesy of Desart

Quietly spoken, with short Centralian vowels, Watkins has lived most of his life within three kilometres of where we are seated in the gardens of Araluen Art Centre. Of the same generation as Perkins, he remembers “significant change, when Aboriginal people’s rights were finally being recognised.” Citizenship, equal wages. “I remember the emergence of the town camps, land rights, the establishment of Legal Aid, CAAMA Media and, of course, the so-called dot painting art movement that emerged out of the western desert. I grew up with all this, I’m fully grounded here, and passionate about the work I do ’cause it’s a continuation of what my old people did, enabling me to be where I am now.”

A common, often fatal, ailment in the region is kidney disease caused by poverty and lack of healthcare, and necessitating regular dialysis. Perkins’ own father, Arrernte activist Charlie Perkins suffered from this, and at Hetti’s ground-breaking Papunya Tula exhibition at Art Gallery of New South Wales in 2000, more than $1 million was raised.

Mervyn Rubuntja’s ‘Tjoritja (West MacDonnell Ranges), NT 2025’.Credit: Fiona Morrison, courtesy of Desart

For decades now, art centres have raised money to build dialysis centres. Purple House, a social enterprise for dialysis patients in Mparntwe, celebrates its 25th anniversary this year with an exhibition of ceramics made from white mud (yarltiri walya). Serena Nakamarra Shannon’s works stood out for their assured spacious designs and were all the more precious for the fact that the artist recently passed away.

There are also the Purple Trucks, mobile clinics that service people in remote communities. They are jaunty, glamorous vehicles, one painted by the late Pintupi artist Patrick Tjungurrayi in his striking, bright blocky style.

In front of an untitled painting by Marcus Camphoo Kemarre (Kaytetye / Alyawarr), a grid of fat, red, confident brushstrokes, I spoke to Harry Price, manager of Arlpwe Art and Cultural Centre. Arlpwe is in country threatened by the largest water licence the Northern Territory government may grant to mining. If it goes ahead, the water table will drop 40 metres, displacing four nations for a second time.

Selinda Davidson’s “Tali tjuta 2025”.Credit: Fiona Morrison, courtesy of Desart

Kemarre is a member of Tennant Creek Brio, the men’s collective who wowed the 2020 Sydney Biennale and ACCA in Melbourne with their gutted, speared pokie machines, punky installations and charged, feral paintings.

“Kemarre has a disability and doesn’t talk about his work, except maybe the colours. These works on paper are new for him. If anything they relate to art history.”

Another example of the positive impact of art centres is how these men have stayed out of jail for most of the past decade, dried out, and found hope for the future.

Alison Milyika Carroll, director of NPY Women’s Council, speaking at Desert Mob Artist Talks.Credit: Sara Maiorino, courtesy of Desart

Artists often move between centres, following kinship obligations, or custodianship of stories on distant country, or perhaps to facilitate a change of media. Innovation and experimentation are constant. Clifford Thompson Japaljarri, another TCB artist, who draws from traditional Warlpiri designs and graffiti, is showing this year with Nyinkka Nyunyu Art Centre. His floor installation of short fracking signs struck through with black horizontal lines is a staunch repudiation of gas exploitation on Warumungu Lands, in solidarity with the same crisis on Indigenous lands in Canada.

The intergenerational representation in Desert Mob is, Perkins and Watkins tell me, the strongest it’s ever been. Selinda Davidson from Ninuku Arts is from a family of artists. She articulates her tali tjuta (sandhills) on canvas and on glass, the latter in collaboration with artist Clare Belfrage from the JamFactory. Davidson is only in her 30s but her shimmering waves of tiny striations show a dexterity and mastery of tone, the painting in the Araluen Arts Centre using graded hues of blue and ochre, the vases emerald green and cobalt blue.

The most striking painting from Papunya Tula Artists was by Angelina Marks Nungurrayi, who departed from the traditional Western Desert style she’s used to date, to create Marnpi, south of Walungurru. This large square canvas of black and charcoal with an undulating divide, a small yellow speckled shape afloat on each side, imprints itself on your memory as starkly as anything by late Gija artist Mabel Juli. Marnpi is the story of marsupial mice that Nungurrayi inherited from her father, Mick Namarari Tjapaltjarri, one of the 1970s pioneers of Papunya whose masterpieces now adorn the walls of institutions across the continent and beyond.

Angelina Marks Nungurrayi’s ‘Marnpi, south of Walungurru (Kintore) 2025’.Credit: Fiona Morrison, courtesy of Desart

Nungurrayi completes her paintings in a couple of days, each rendition of the same story differing greatly. The Marnpi selected for Desert Mob had a confidence, refinement and command greater than her works in Papunya Tula in town, perhaps indicating the significance of Desert Mob to artists. At Desert Mob for the first time, Nungurrayi was nervous when I spoke to her at the opening but by the end of the weekend, aware of her impact and the status of her legacy, she was waving with excitement. “I’m gonna go home, get some really big canvas now!”

Perkins spoke about the increasingly collaborative process of curating Desert Mob. The sagacious eye of her and Aspen Beattie (Luritja / Warumungu / Yawuru) co-curating, were evident in the choices of prolific or known artists such as Nungurrayi, or Grace Kemarre Robinya from Tangentyere Artists, who paints rainheads: chunky white clouds releasing blue driving rain.

Tjanpi Desert Weavers “Tjapu-tjapu inkama! (Play ball!)” 2025. Credit: Fiona Morrison, courtesy of Desart

Or Vanessa Inkamala and Mervyn Rubuntja from Iltja Ntjarra Many Hands Arts Centre, who participated in a project directed by Tony Albert to reinterpret the Albert Namatjiras which were made into postage stamps in 2002. These rich, subtle watercolours of Tjoritja (West Macdonnell Ranges), postmarked 45¢, undulated along one wall like the mountains themselves, reinventions of reinventions, their uncanny likeness echoed again by the actual landform visible every day from town.

A week before Desert Mob began, four hours drive north-west, Utopia Art Centre opened a new building providing climate-controlled spaces for the artists who previously worked in makeshift sheds. Built with a combination of sales – their greatest star being the late Emily Kam Kngwarray (Anmatyerr) – and state and federal government funds, the building is a hallmark of community and cultural resilience, and hope for the future.

Contradictions abound. The tremendous economic success of art centres does not palliate the demands on these communities. The cost of travel, materials, goods and services is extremely high. And while Creative Australia’s recent national cultural policy, Revive, places First Nations as the first pillar of that policy, it only mentions art centres once.

Loading

“Every Australian has the right to workplaces fit for purpose,” Watkins says. “But many centres are in old buildings, poorly ventilated and insulated. In view of the rise in temperatures, we need more long-term investment in jobs, in work skills programs for instance.”

Harry Price concurs. “It’s still not easy. It’s stressful living in places like Tennant Creek, it’s really industrial. They’re standing up to mining, they’ve got big obligations to their communities, a lot of people to support, medical bills. Two of the fellas are chairing an organisation to build sustainable housing all funded with their artwork.”

With temperatures set to rise three degrees because of climate change, many are afraid of more forced movement. As Watkins says: “Without art centres, the platforms for communities to share these stories with the world would not exist.”

And so the story continues.

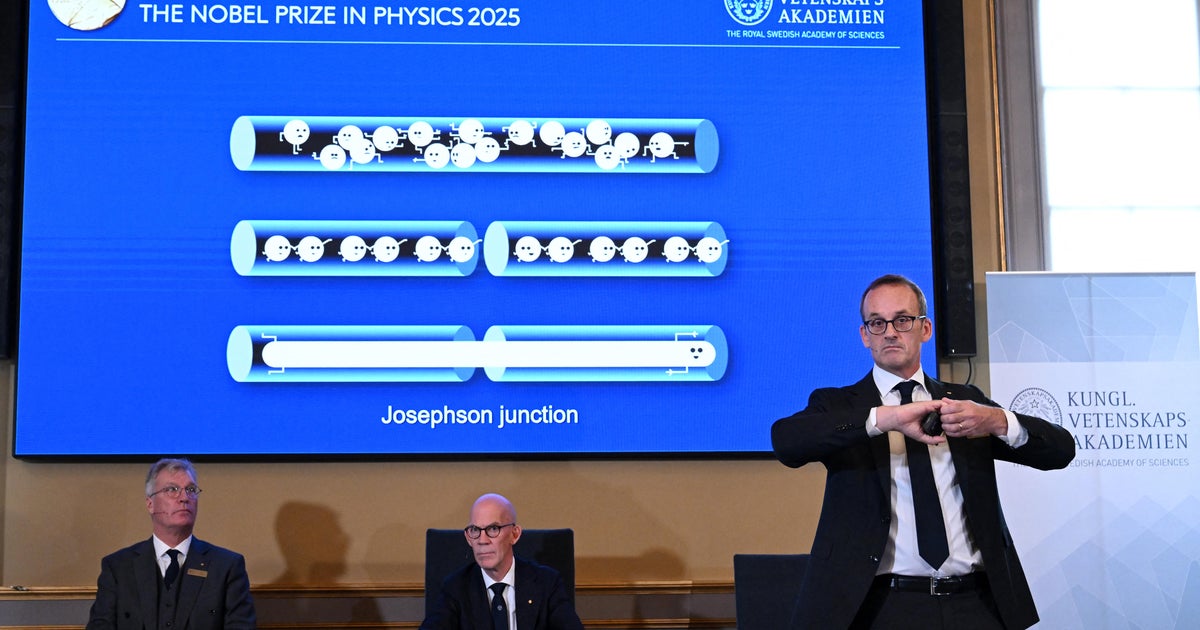

Desert Mob takes place in Mparntwe / Alice Springs until October 26.