By Pat Sheil

October 1, 2025 — 12.00pm

Credit:

BIOGRAPHY

Collisions

Alec Nevala-Lee

Norton, $52.95

“Curious people,” according to Nobel Prize-winning physicist Luis Alvarez, “had the right to exhibit a controlled disrespect for authority.” In this revealing, and at times disturbing biography, Alec Nevala-Lee follows the tempestuous career of one of the most curious characters of 20th-century science. Both inquiring and peculiar. Curious.

As a physicist, Alvarez is best known for his work on the Manhattan Project, which led to the atomic weapons used in 1945, though his 1968 Nobel Prize was awarded for his discovery of “resonance states” in particle physics.

Readers should not be put off by the fact that they, like me until last week, have no idea what a resonance state was, is or even means. It doesn’t matter. This fascinating story isn’t about resonance states. It’s about Luis Alvarez.

Putting nuclear physics aside for the moment, many readers will have heard the name Alvarez in what seems at first blush to be an utterly unrelated piece of work, the asteroid impact theory of the extinction of the dinosaurs. In 1980, Alvarez and his geologist son, Walter, proclaimed to a deeply sceptical paleontological establishment that the disappearance of giant reptiles at the end of the Cretaceous period, some 65 million years ago, was caused by a massive chunk of space rock smashing into the earth.

A fortuitous family affair, it was Walter who noticed the subtle layer separating fossil-rich Cretaceous rocks from the fossil-poor strata piled above them, and his physicist father who worked out that by measuring isotopes of iridium (rare on earth, plentiful in asteroids), they could establish that the big lizards were killed off in very short order, not the millions of years of conventional wisdom.

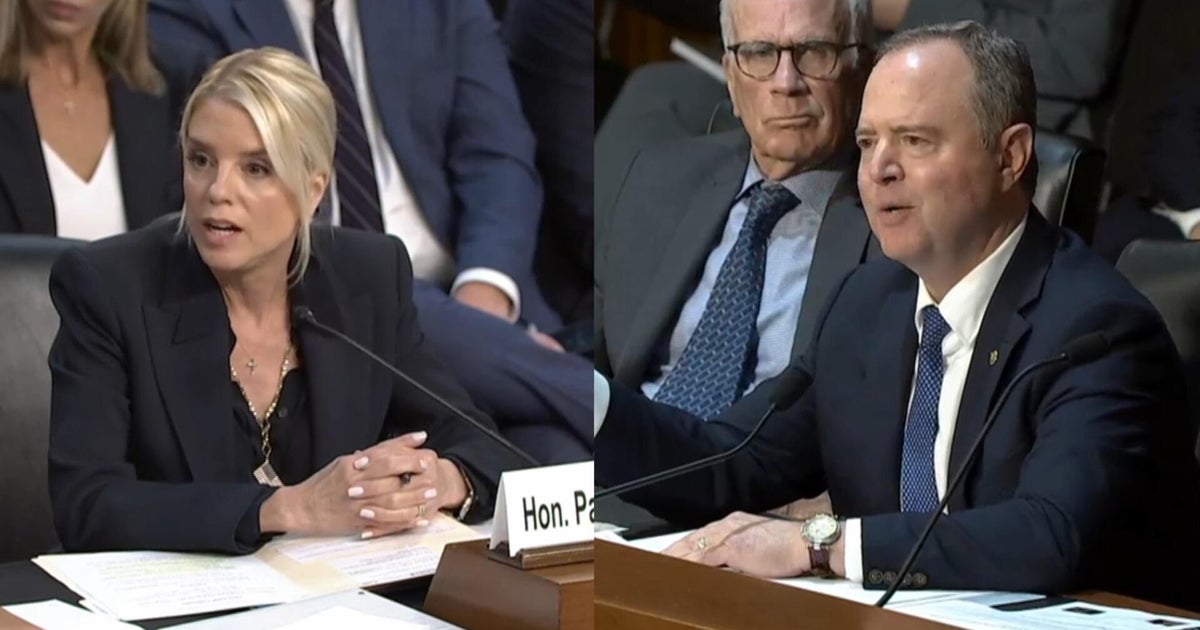

Alvarez (right) with his son Walter.Credit: Corbis/VCG via Getty Images

Nevala-Lee’s book is a fine example of intriguing, explanatory science writing as much as a biography, and as such traces his subject’s life through his work and the scientists he both collaborated and fought with. There is little here about his two marriages and four children (except Walter), and indeed, if his cantankerous reputation among his peers is anything to go by, Alvarez would not have been the easiest person to live with.

But if he was no diplomat, he was a brilliant physicist and a hands-on lab man of the old school. If he needed a piece of equipment that didn’t exist, he would twist arms to get the money and build the thing himself. By 1940, along with just about everyone with valued skills in physics and chemistry, he was up to his elbows in building weapons, in his case, radar navigation.

The radar antennae and bases used by the British to detect German bombers were big gadgets. Alvarez transformed them into airborne bomb sights and navigational aids to help planes land at night and in fog, making the success of the 1948 Berlin Airlift possible.

His genius was not that of a theorist, like Einstein or Dirac, but as an experimentalist, and it was his counterintuitive leaps into designing detectors and accelerators that led to his Nobel.

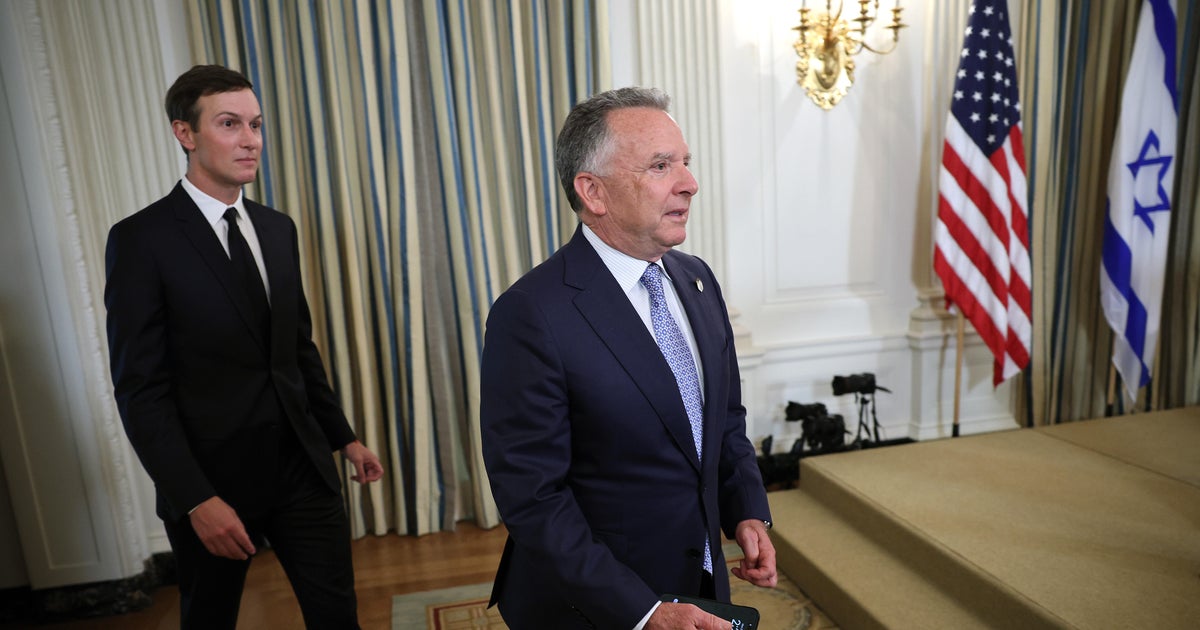

Alvarez (pictured in 1969) was famously grouchy, but brilliant.Credit: United Press International Photo

The “resonance state” work that won him his prize was for designing, building and using a device called a hydrogen bubble chamber to reveal new subatomic particles. When Alvarez started in physics, the atom was a fairly simple unit of matter, consisting of neutrons, protons and electrons. By the time of his death in 1988, hundreds of new particles had been discovered, many by Alvarez in his bespoke detectors.

If a theorist postulated a new creature to add to the growing “atomic zoo” of muons, mesons and anti-particles, Alvarez had a knack for building the contraption that would find it. Or find that it didn’t, or couldn’t, exist. Nevala-Lee performs a similar feat with his book – he takes us inside the mind of a driven, abrasive, gifted physicist who wanted, indeed needed, to be where the action was, and in his day, that was the physics lab at Berkeley University in California.

Loading

Unless it was at Los Alamos or, in August 1945 at Tinian airfield in the Pacific, where he signed his name on the side of the Hiroshima bomb Little Boy before boarding The Great Artiste, the observation plane that followed the Enola Gay to Japan.

When Hiroshima was destroyed, Alvarez was staring at an oscilloscope screen at the rear of the plane. The white flash filled the plane from the cockpit windows, but the wave form on his machine had told him what was about to happen.

Then the shock wave hit.

“Even at a distance of eleven miles, it was like sitting on a trash can that had been hit by a baseball bat. The whole plane seemed to crinkle, making a cracking sound like snapping sheet metal.”

Alec Nevala-Lee has written a fine book about a brilliant, if difficult, scientist. And yes, physics can be scary.

The Booklist is a weekly newsletter for book lovers from Jason Steger. Get it delivered every Friday.

Most Viewed in Culture

Loading