The squiggle lives.

For 40 years Norman Hetherington was known for his creation, Mr Squiggle, a blue-haired man from the moon who used his pencil nose to turn a child’s squiggle into a giggle.

From 1959 to 1999 on ABC television, Mr Squiggle, a puppet made, voiced and operated by Hetherington, transformed 10,000 children’s drawings into what they saw as masterpieces.

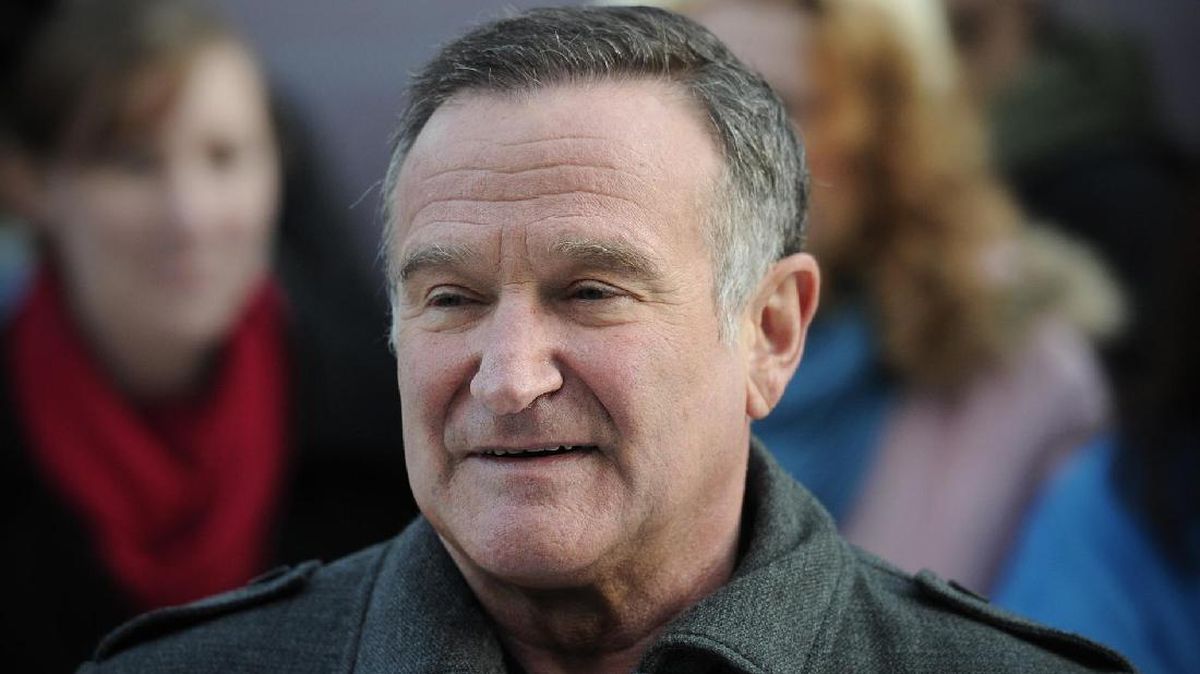

Rebecca Hetherington with some of her father’s creations, including Mr Squiggle.Credit: NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AUSTRALIA

“It’s a duck that wants to be a ballet dancer,” he said of one. Very often they were drawn upside down.

Now the next generation can have a squiggle. A new exhibition, Mr Squiggle and Friends, The Creative World of Norman Hetherington opening at the National Museum of Australia on Friday includes an interactive screen where a new generation can turn an original squiggle into a drawing of their own.

It includes nearly 300 objects from the Hetherington collection of more than 800 items, including hundreds of puppets, and was curated by museum deputy director Dr Sophie Jensen.

Jensen said that as a unique piece of Australian history, it was hard to imagine another television program that had touched as many people as Mr Squiggle.

“It doesn’t matter who you talk to,” she said, someone will have been on the show, watched it or knew someone who was on it. “It’s part of its magic. You only get that with a show that was on the air for 40 years, that covers generations. And 1959 to 1999 was a pretty remarkable stretch in Australian life.

“And I love that about Mr Squiggle. If I think about the impact that he might have had over the period – that’s 10,000 kids who would have sat glued to that screen just hoping their name would appear on the screen.”

Jensen said it was a tribute to the power of children’s television. “I think we engage with it in a really emotional way. It is a safe place, something that becomes embedded in our memories … Mr Squiggle was talking directly to children about something they were creating together. And it was not like winning a prize – it was just that moment of absolute beautiful, artistic connection between this unique character and generations of Australian children.”

Childhood memories were anchored to the show and its presenters. “Everyone dates themselves by the presenter: you are either a Miss Pat person (Pat Lovell), a Miss Jane, or a Roxanne or Rebecca person.”

Over the years, changes in the names, the clothes and how we talked were reflected in the show. “By the time we get to Roxanne and Rebecca, we have dropped the Miss.”

Hetherington’s daughter Rebecca, the last presenter, told Australian Story that the line between her father and Mr Squiggle was blurred: “There is no Mr Squiggle without him, but there is no Hetherington without Mr Squiggle.”

The show was an all-consuming family affair, with his wife Margaret eventually taking over scriptwriting. The tradition continues today. Norman’s grandson Tom is also a puppeteer and features in the exhibition.

Loading

When Hetherington died aged 89 in 2010, he left behind a studio full of hundreds of handmade puppets – often made from bits of leftover materials – including the well-known cast of Mr Squiggle, the one-eyed Blackboard, Rocket, Bill the Steam Shovel, and Gus the Snail.

Hetherington honed his skills in the army entertainment unit in World War II performing and drawing soldiers caricatures on stage. Though Mr Squiggle didn’t debut until 1959, his puppets Nicky and Noodle, debuted on the opening night of ABC TV in 1956, while his other creations, Jolly Jean and his fun machine premiered with Channel Seven in 1957.

Many puppets of the that time were angry and aggressive. But Jensen said Hetherington deliberately crafted a character who wanted his hand held. “I think that’s what you’re responding to, is that just the beautiful, gentle nature that Squiggle brought to the screen.”

Mr Squiggle liked to joke and pun. “You like it?” Mr Squiggle asked Miss Pat in a 1959 episode where he tricked her into thinking he was drawing an owl. When Miss Pat said she did, Mr Squiggle replied, “The owl does give a hoot,” and turned the sketch of an owl into a cat.

Mr Squiggle would always acknowledge the child by name. It was the Sydney Morning Herald journalist Michael Ruffles’ first byline. Ruffles recalls his excitement as a preschooler in the 1980s when he saw his name flashing across the screen. He expected Mr Squiggle would turn his drawing into clouds. Instead it was turned into a drawing of bumpy tracks for the character Bill the Steam Shovel. As a senior editor he often channels the grumpy catchcry of another puppet, Blackboard, to urge reporters to “Hurry Up!”

Start the day with a summary of the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up for our Morning Edition newsletter.

Most Viewed in National

Loading