Peter Costello’s baby bonus encouraged Australians to have extra children, particularly among women on low or no incomes, the first research of its kind has confirmed, with each extra child costing taxpayers $86,000.

While the research, by the independent e61 think tank, suggests that in its first year of operation the bonus delivered an extra 16,250 babies, those behind the work cautioned such a generous handout may not work as well today given other financial supports in place for families.

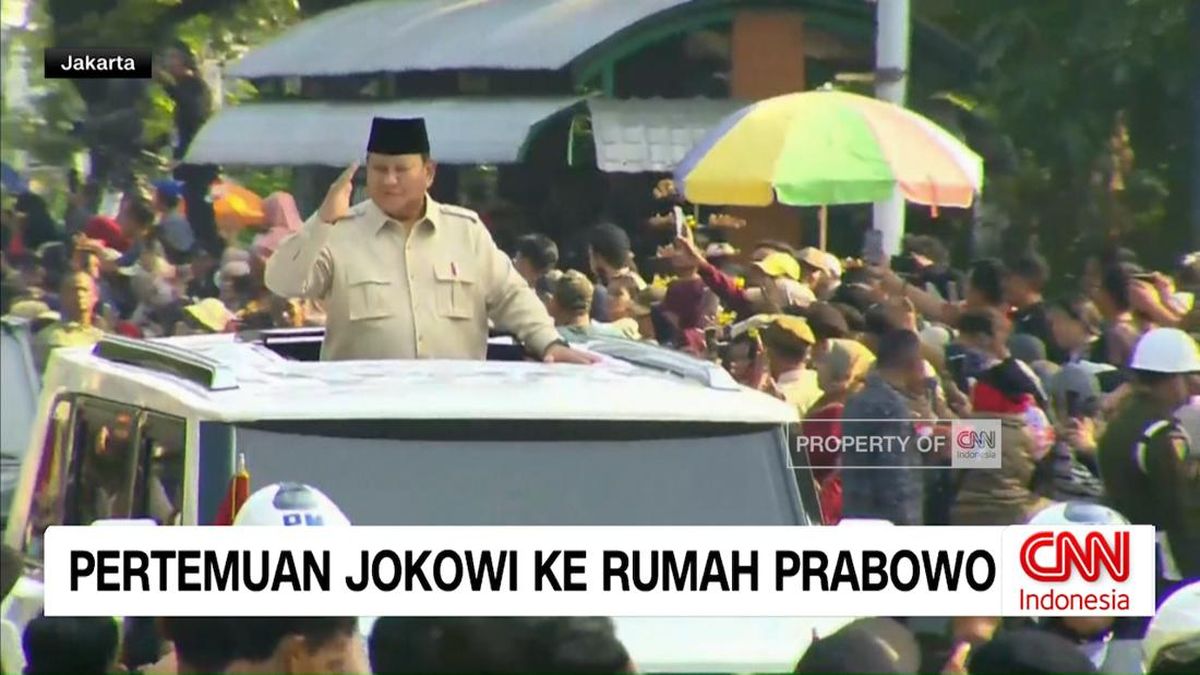

Former treasurer Peter Costello unveiled the baby bonus in 2004. New research it increased births by 1300 a month.Credit: Sandy Scheltema

And the research has already come under fire for ignoring long-term demographic trends and the failure of similar and even more generous pro-baby payment policies across the rest of the world.

The decade-long bonus started in mid-2004 when Costello famously encouraged Australians to have more children, declaring couples should “have one for your husband and one for your wife and one for the country”.

Ever since its introduction, there have been arguments over whether the bonus got Australian couples in the mood for more babies.

Loading

But research manager with e61, Pelin Akyol, said the baby bonus had lifted fertility among Australian women, with 16,250 additional children born in its first year of operation alone and the policy driving an extra 1300 babies a month.

“Women exposed to the policy were more likely to end up with three or more children in total,” she said.

“This is the first evidence that the baby bonus increased long-term family size, not just the timing of births.”

The nation recorded 251,161 births in the year before the bonus started. By 2008, births had climbed to 302,272, before peaking at 315,417 in 2018. Since then, births and total fertility rates have fallen, with 286,998 births recorded in 2023.

The baby bonus changed during the Howard government’s final years. Initially a payment of $3000, it was increased to $4000 and then $5000.

The study found the $3000 payment had the largest impact, with much more modest increases at the higher rates. The researchers also found the first child tax refund, worth up to $12,500 and which the bonus replaced, had “no detectable effect on fertility”.

The largest impact was on women who had not finished year 12, with an 8 per cent lift in births among this cohort. There was a 10 per cent lift among women with no taxable income, and an 8 per cent lift among women with below-median incomes.

The researchers found a 9 per cent increase in births of a third or a fourth child.

Every total additional birth attributable to the bonus program cost taxpayers, in today’s dollars, $86,000.

Akyol and fellow researcher Ali Vergili warned that a repeat of the baby bonus may not be successful today.

They noted that prospective families now had access to broader financial supports, such as paid parental leave (which did not exist when the bonus was introduced) and expanded childcare.

ANU demographer Liz Allen says demographic destiny rather than the baby bonus accounted for early 2000s lift in fertility.Credit: Alex Ellinghausen

But Australian National University demographer Liz Allen said there were substantial doubts over the study’s findings, which were counter to the muted impact of even more generous policies over recent years.

Many nations have introduced a suite of pro-baby policies. Hungary, for instance, now offers large interest-free loans to childbearing woman, subsidised minivans and a lifelong exemption from income tax for mothers with at least four children. But its fertility rate continues to fall and is now around just 1.4 children per woman.

Loading

Allen said the research ignored the “demographic echoes” that had lifted Australia’s fertility rate in the early 2000s.

Australia’s post-World War Two fertility rate peaked at 3.55 in 1961 and then fell before rallying again in the early 1970s as Baby Boomers started their families. From that point, fertility fell to its lowest level on record in 2001 just as Generation X women moved into their prime child-rearing years.

Between 2001 and 2008, Australia’s fertility rate increased 16 per cent to 2.02. But between 2008 and 2014, even with the bonus continuing, the nation’s fertility rate dropped by 11 per cent.

“The baby bonus and other programs did not lead to a baby boom. It was demographic destiny that played out,” Allen said.

“It’s gob-smacking to think that we in Australia are an outlier to the rest of the world, which is going even further with financial incentives.”

Allen said a host of issues, from the cost of housing to economic insecurity to climate change, was behind the drop in fertility.

She argued for those people who want children, the impediments just continue to grow.

“The evidence is clear we need a suite of policies if we are going to turn around the train wreck that we have playing out. It’s going to be stubbornly difficult to turn around, and we probably can’t do that,” she said.

Most Viewed in Politics

Loading