In July, David Sacks, one of the Trump administration’s top technology officials, beamed as he strode onstage at a neoclassical auditorium just blocks from the White House. He had convened top government officials and Silicon Valley executives for a forum on the booming business of artificial intelligence.

The guest of honour was President Donald Trump, who unveiled an “AI Action Plan” that was drafted in part by Sacks, a longtime venture capitalist. In a nearly hour-long speech, Trump declared that AI was “one of the most important technological revolutions in the history of the world”. Then he picked up his pen and signed executive orders to fast-track the industry.

Almost everyone in the high-powered audience – which included the CEOs of chipmakers Nvidia and AMD, as well as Sacks’ tech friends, colleagues and business partners – were poised to profit from Trump’s directives.

Among the winners was Sacks himself.

Loading

Since January, Sacks, 53, has occupied one of the most advantageous moonlighting roles in the federal government, influencing policy for Silicon Valley in Washington while simultaneously working in Silicon Valley as an investor. Among his actions as the White House’s artificial intelligence and crypto tsar:

- Sacks has offered astonishing White House access to his tech industry compatriots and pushed to eliminate government obstacles facing AI companies. That has set up giants like Nvidia to reap an estimate of as much as $US200 billion ($300 billion) in new sales.

- Sacks has recommended AI policies that have sometimes run counter to national security recommendations, alarming some of his White House colleagues and raising questions about his priorities.

- Sacks has positioned himself to personally benefit. He has 708 tech investments, including at least 449 stakes in companies with ties to artificial intelligence that could be aided directly or indirectly by his policies, according to a New York Times analysis of his financial disclosures.

- His public filings designate 438 of his tech investments as software or hardware companies, even though the firms promote themselves as AI enterprises, offer AI services or have AI in their names, the Times found.

- Sacks has raised the profile of his weekly podcast, All-In, through his government role, and expanded its business.

No event better illustrates Sacks’ ethical complexities and how his intertwined interests have come together than the July AI summit. Sacks initially planned for the forum to be hosted by All-In, which he leads with other tech investors. All-In asked potential sponsors to each pay it $US1 million for access to a private reception and other events at the summit “bringing together President Donald Trump and leading AI innovators”, according to a proposal viewed by the Times.

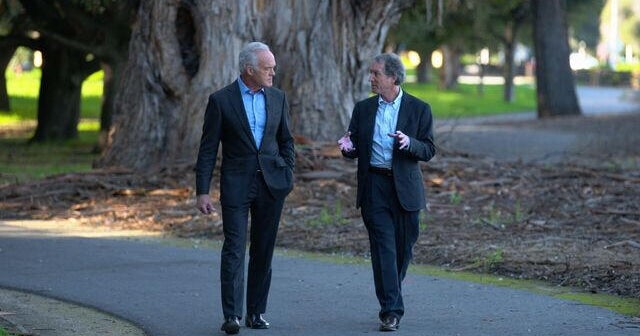

David Sacks, Trump’s AI and crypto tsar, has continued to work as a Silicon Valley investor.Credit: NYT

The plan so worried some officials that Susie Wiles, the White House chief of staff, intervened to prevent All-In from serving as the sole host of the forum, two people with knowledge of the episode said.

Steve Bannon, a former adviser to Trump and a critic of Silicon Valley billionaires, said Sacks was a quintessential example of ethical conflicts in an administration where “the tech bros are out of control”.

“They are leading the White House down the road to perdition with this ascendant technocratic oligarchy,” he said.

Sacks has been allowed to serve in government while working in private industry because he is a “special government employee”, a title the White House typically confers on experts who temporarily advise the government. He is not paid for his work for the administration.

In March, Sacks received two White House ethics waivers, which said he was selling or had sold most of his crypto and AI assets. His remaining investments, the waivers said, were “not so substantial” as to influence his government service.

But Sacks stands out as a special government employee because of his hundreds of investments in tech companies, which can benefit from policies that he influences. His public ethics filings, which are based on self-reported information, do not disclose the value of those remaining stakes in crypto and AI-related companies. They also omit when he sold assets he said he would divest, making it difficult to determine whether his government service has netted him profits.

White House spokeswoman Liz Huston said Sacks had addressed potential conflicts. His insights were “an invaluable asset for President Trump’s agenda of cementing American technology dominance”, she said.

Jessica Hoffman, a spokeswoman for Sacks, said that “this conflict of interest narrative is false”. Sacks had complied with special government employee rules and the Office of Government Ethics determined that he should sell investments in certain types of AI companies but not others, she said. His government role had cost him, not benefited him, she added.

White House chief of staff Susie Wiles was concerned by Sacks’ plan for his podcast, All-In, to host an AI summit in July.Credit: Bloomberg

At a White House dinner for tech executives in September, Sacks said he was grateful to work in both technology and government. It was “a great honour to have a foot in each one of these worlds”, he said.

‘David’s House’

Sacks’ road to the White House began in Silicon Valley.

He arrived in the tech heartland in 1990 as an undergraduate at Stanford University, where he met fellow students including Peter Thiel. Sacks later joined Thiel at a start-up that became the electronic payments firm PayPal, alongside Elon Musk.

Loading

After eBay bought PayPal for $US1.5 billion in 2002, the men invested in one another. Sacks helped fund Musk’s rocket company, SpaceX, as well as Palantir, the data analysis firm co-founded by Thiel. In turn, Thiel backed Yammer, Sacks’ business communications start-up that was sold to Microsoft in 2012 for $US1.2 billion.

In 2017, Sacks began Craft Ventures, a firm that has invested in hundreds of start-ups, including some owned by his friends. He also started the All-In podcast three years later with friends and fellow investors Jason Calacanis, Chamath Palihapitiya and David Friedberg.

Sacks became a major player in Republican politics in 2022, when he donated $US1 million to a super political action committee supporting the Senate run of JD Vance, a former tech investor who worked for Thiel and now the vice president.

Last year, Sacks hosted a $US12 million fundraiser for Trump at his San Francisco mansion. The dinner made an impression on the presidential candidate.

“I love David’s house,” Trump said on All-In two weeks later. “What a house.”

After the election, Trump’s team asked Sacks to join the administration. He said he would, as long as he could continue working at Craft – and got his wish.

“It’s exactly what I requested,” Sacks said of his dual position in December.

Allying with Nvidia

Sacks opened the door of the White House to Silicon Valley leaders. Among the most prominent visitors was Jensen Huang, Nvidia’s CEO.

Sacks and Huang, who had not met before Sacks joined the administration, forged a tight bond this spring, said three people familiar with the men, who were not authorised to discuss their interactions.

Both stood to benefit. Huang, 62, wanted government clearance to sell Nvidia’s highly coveted AI chips around the world, despite security concerns that the components could bolster China’s economy and military. Huang argued that restricting exports of Nvidia’s chips would push Chinese companies to develop more powerful alternatives. And spreading Nvidia’s technology would expand the AI industry, aiding the AI investments owned by Sacks and his friends.

Steve Bannon, a former adviser to Trump and a critic of Silicon Valley billionaires, says Sacks is a quintessential example of ethical conflicts in an administration where “the tech bros are out of control”.Credit: Bloomberg

In White House meetings, Sacks echoed Huang’s ideas that the best way to beat China would be to flood the world with American technology. Sacks worked to eliminate Biden-era restrictions on Nvidia and other American chip companies’ sales to foreign countries. He also opposed rules that would have made it difficult for foreign companies to buy US chips for international data centres, five people with knowledge of the White House discussions said.

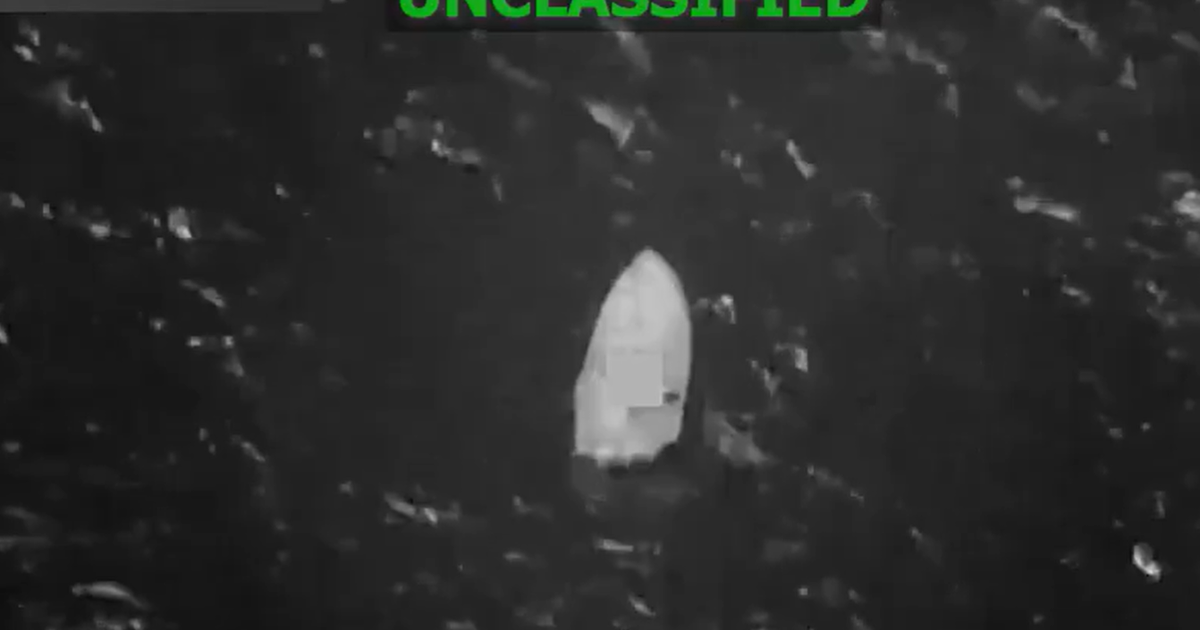

Free of those restrictions, Sacks flew to the Middle East in May and struck a deal to send 500,000 American AI chips – mostly from Nvidia – to the United Arab Emirates. The large number alarmed some White House officials, who feared that China, an ally of the UAE, would gain access to the technology, these people said.

But the deal was a win for Nvidia. Analysts estimated that it could make as much as $US200 billion from the chip sales.

Hoffman said Sacks developed his thinking by talking to many people, not just Huang, and “wants the entire American tech stack to win”. None of his holdings benefited from the UAE deal, she said.

Nvidia spokeswoman Mylene Mangalindan said Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick was the company’s primary contact for AI chip sales abroad.

The Sacks Portfolio

The White House has praised Sacks, saying he minimised his financial conflicts of interest.

Loading

The ethics waivers that Sacks received said he and Craft Ventures had sold more than $US200 million in crypto positions, including investments in bitcoin, and were divesting stakes in AI-related companies including Meta, Amazon and xAI.

Sacks had started or completed sales of “over 99 per cent” of his “holdings in companies that could potentially raise a conflict of interest concern”, the White House said.

Huston, the White House spokeswoman, said Sacks was “recused from participating in any matters that could affect his financial interests until he was able to divest of conflicting interests or until he received a waiver”.

But Sacks’ waivers provide an incomplete picture of his wealth and do not say when he sold his holdings in Meta, Amazon and other companies.

What is clear is that Sacks, directly or through Craft, has retained 20 crypto and 449 AI-related investments, according to the Times analysis.

Of the AI-related investments, 11 were designated in one waiver as “AI Interests”. The other 438 were classified as software or hardware makers, even though they promote AI offerings or services on their websites. In one example, the waiver categorised Palantir as “software as a service”, while the company’s website says it provides “AI-Powered Automation for Every Decision”. Forty-one of the companies have AI in their names, such as Resemble.AI and CrewAI.

In one of the waivers, the White House said many of the software companies “do not currently use AI-related applications in their core business in any material way”, but added that “many of them are likely to at some point in the future”.

Policies that Sacks supported at the White House have laid the groundwork for his investments to flourish.

The AI Action Plan promoted domestic production of autonomous drones and other AI inventions for the Pentagon. Sacks has stakes in defence tech start-ups such as Anduril, Firestorm Labs and Swarm Aero that make drones and other products, according to his filings. In September, Anduril announced a $US159 million contract with the US Army to build a new type of night vision goggles with AI.

Sacks at his then home in Los Angeles in 2005. His road to the White House began in Silicon Valley. Credit: NYT

Shannon Prior, an Anduril spokesperson, said the company had a relationship with the army before the AI Action Plan and that it received the contract because its founder, Palmer Luckey, is “the world’s best virtual reality headset designer”. Hoffman said it was an “obvious idea” to include the military use of AI in the policy plan.

This spring, Sacks also backed a bill called the GENIUS Act to regulate stablecoins, a type of cryptocurrency designed to maintain a constant price of $US1. Sacks promoted the legislation on CNBC and worked to advance it through Congress.

After the bill passed in July, Sacks called it “historic” and “momentous” on All-In. It is poised to significantly expand the stablecoin business.

One of Craft’s crypto investments is BitGo, a company that works with issuers of stablecoins. BitGo celebrated the GENIUS Act on its website and promptly capitalised, declaring that its service “fit perfectly” with the new guidelines. “The wait is over,” the site said.

Trump at the White House crypto summit in March with (from left) Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, a staff member, Sacks and Bo Hines, a member of the presidential council of advisers for digital assets.Credit: AP

In September, BitGo filed for an initial public offering. Craft owns 7.8 per cent of the company, according to financial filings, which would be worth more than $US130 million at BitGo’s 2023 valuation.

BitGo declined to comment. Hoffman said the GENIUS Act’s passage “contained no specific benefit for BitGo”.

Going All-In

In an All-In episode in March, two of the podcasts’ hosts, Friedberg and Palihapitiya, stood outside the East Wing.

They had been “running around” the White House, Palihapitiya said, as the show spliced in photos of them walking through wainscoted rooms and joining Sacks in the portico dividing the East and West wings.

The podcasters then interviewed Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent about economic policy. Days later, they returned with a nearly two-hour interview with Lutnick. Two months after that, they interviewed the secretaries of agriculture and the interior. In September, All-In posted a video of a private Oval Office tour with Trump.

Loading

Sacks’ government work has boosted the profile of the podcast, which is downloaded 6 million times a month. Its annual conference in Los Angeles generated roughly $US21 million in ticket sales this year, up from $US15 million last year, based on its $US7500 ticket price and public attendance estimates. In June, the podcast introduced a $US1200 All-In-branded tequila.

Sacks has forgone AI and crypto-related revenues, such as from sponsorships, but can share in sales from tequila and event tickets, Hoffman said. Jon Haile, the podcast’s CEO, did not respond to a request for comment.

Sacks’ personal business and policy work came together at the July AI event in Washington, which he tapped All-In to host.

In the keynote speech, Trump described Sacks as “great” before signing executive orders to speed the building of data centres and exports of AI systems.

Then he handed Sacks the presidential pen.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

The Business Briefing newsletter delivers major stories, exclusive coverage and expert opinion. Sign up to get it every weekday morning.