As a stay-at-home mum with family interstate and no childcare support, Rachel Gold found herself relying on digital devices to keep her daughter occupied.

“I definitely leant on screen time to give me that little bit of reprieve, so I felt like I could take a breath,” she says.

“Even though the recommendation is for kids to not have screen time before two, I’d seen all over social media that it was very normal for babies and toddlers to have some form of screen time.”

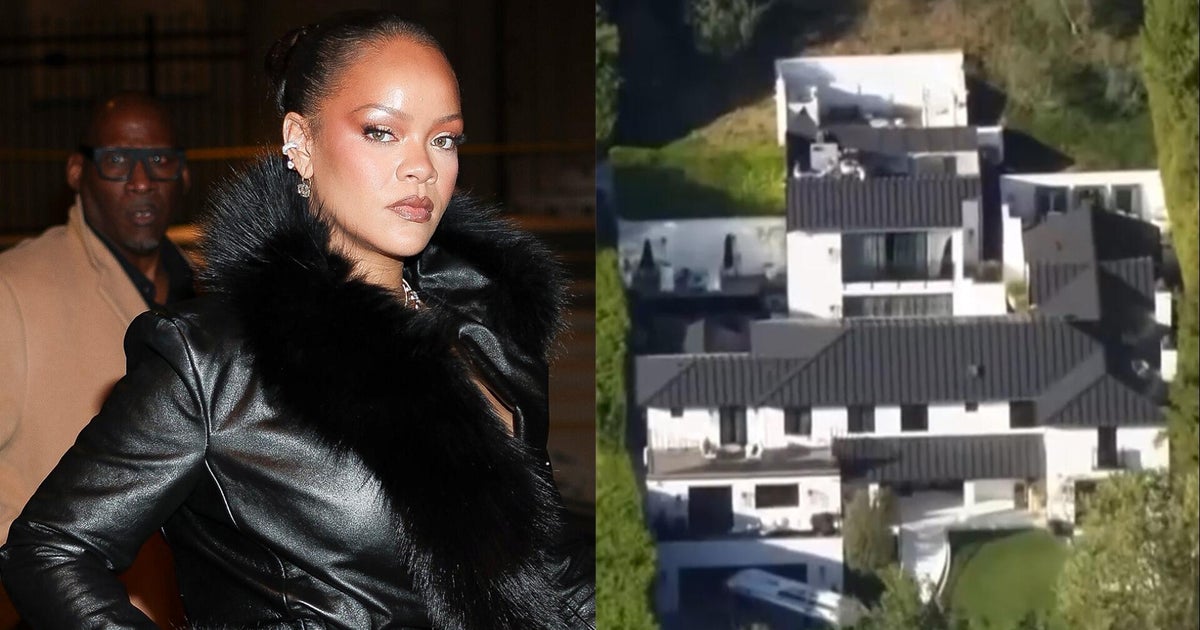

Sydney mother Rachel Gold with her youngest daughter.Credit: Louise Kennerley

But as her daughter got older, Gold became concerned with her “engaging with shows for longer” and “getting upset when I switched them off”.

So, with a six-week-old at home (her second daughter) – “the worst possible time”, as she says – Gold decided to cut her toddler’s screen time cold turkey.

Loading

She was surprised to discover how quickly her daughter, now four, adjusted. The change was harder on her.

“Screen time is not for them, it’s for us. We’re the ones that struggle. It’s like, ‘Oh, well now she hasn’t got this other thing to entertain her, so it’s all on me and my husband to guide her into other things’.”

More than six months on, Gold has noticed a marked improvement in her daughter’s patience and independence. She can now happily play alone.

“At first, it might be that initial frustration, but now she can quickly find a way to entertain herself, whereas before it would just be a complete meltdown,” she says.

What do the guidelines say?

National guidelines recommend no screen time for infants under two, no more than one hour per day for kids between two and five and less than two hours per day for those aged five to 17. The World Health Organisation recommends no more than an hour a day for two-year-olds, with less time preferred, and no more than an hour per day for three and four-year-olds.

Still, 90 per cent of Australian children aged five to 14 use screens, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics. Of this cohort, almost a quarter spent at least 20 hours per week on screens, or almost three hours per day.

For infants, an Australian study from 2023 found that at six months, children were exposed to an average of one hour and 16 minutes of screen time per day, which increased to an average of two hours and 28 minutes by 24 months.

The pressures of modern parenting

Dr Sumudu Mallawaarachchi, a research fellow at the Australian Research Council’s Centre of Excellence for the Digital Child, says time-based guidelines for screen use are overly simplistic, and were devised in the late 2000s before digital technology became deeply embedded in our lives.

She empathises with parents like Gold, whom she says are navigating rising cost of living pressures, the decline of the “village” and the changing role of technology in our lives.

A common theme in her research with parents is the sentiment “you’re damned if you do, damned if you don’t: they’re often judged for using devices, especially mothers in public places or by extended family, but if you don’t use devices, or if the child is misbehaving, then also you get blamed”.

Jacquelyn Harverson, a graduate researcher at Deakin University, agrees “parents today are juggling a lot of different priorities”.

Loading

“We’ve got work from home, which is wonderful, but it means that parents are present, but still not available ... screens are used in that babysitting capacity.”

In a 2021 poll from the Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne, excessive screen time was the top concern for parents, while research has found parental guilt over their kids’ screen time is common.

Given that women still carry out significantly more housework than men, mothers in particular can bear the brunt of this guilt.

Parents of multiple children can also find it harder to meet screen time guidelines.

Tash Ching is a paediatrician and mother of three boys aged two months, one and three. While she has always believed in low screen time for her kids – “they need to have the opportunity to be bored”, as she says – this hasn’t always been realistic, particularly after her second was born.

“It was just survival,” she says. “I think it started when my eldest just wanted to watch kids’ music videos. And I was like, ‘you know what? I’m falling asleep in the chair, so I’m going to let you watch my phone’. It definitely became a second parenting tool.”

Like Gold, she found her eldest can struggle when screens are taken away.

“There were a lot more tantrums, a lot more dysregulation and meltdowns occurring after screen time, especially if they’ve been prolonged. So that made us very mindful about bringing in healthier boundaries.”

Ching says she’s learnt to be kind to herself when it comes to screen time.

“We can’t parent out of an empty cup,” she says.

“If parents need to utilise small breaks with screens, then that actually can still make you a better parent.”

Tash Ching, a paediatrician and mother of three, wants parents to be kinder to themselves about managing screen time.Credit: Paul Jeffers

Screen time and children’s development

Too much screen time for kids has been linked to poorer outcomes in areas such as sleep, depression, language and cognitive development.

A systematic review from this year, co-authored by Harverson, found more digital technology use in children aged four to six was associated with poorer wellbeing outcomes across psychosocial wellbeing, social functioning, the parent-child relationship and behavioural functioning.

However, Harverson points out most research only looks at the impact of time use on development. Indeed, the systematic review also looked at emerging research that shows the relationship between technology and children’s wellbeing is complex.

She adds that time-based guidelines for screens have been developed in the context of guidelines for physical activity, with the assumption that screen time equals sedentary time.

“I was speaking to Foundation and Year One students about what they did with technology, and they talked about using technology to learn dances with their friends. So they’re doing that physical activity, as well as socialising and getting those amazing positive social skills,” she says.

Loading

Indeed, emerging research shows that not all screen time is created equal, says Mallawaarachchi, who calls for a more nuanced and holistic understanding of technology and kids.

A 2024 systematic review and meta-analysis of 100 studies worldwide, co-authored by Mallawaarachchi, found that context matters when it comes to screen time.

Program viewing (including television and YouTube) and background television exposure were associated with poorer psychosocial outcomes in children.

However, co-use (watching and/or discussing content with an adult) was positively associated with cognitive outcomes.

Similarly, the type of content children view matters, with research showing children’s and educational material can be positively associated with things like attention, executive function and language.

Today, Ching says one of the main times her eldest watches television is with his grandfather – and only after a trip to the park first. She’s selective about what her son watches too, favouring children’s shows like Bluey or Paw Patrol or YouTube videos of adults and kids building train sets.

Gold’s eldest now watches television once a week, while her youngest has not yet been exposed to screens.

How to help kids develop better screen habits

- Be intentional: Mallawaarachchi’s top tip for parents is to think about why you are using a screen. For example, are they watching a show that might encourage dancing or physical activity? Are they watching something like Bluey, that can contain important social messages? Or are they FaceTiming relatives, which can be a tool for social connection?

- Use devices together as much as possible: While it can be tricky, aim to find time to engage with screens with your child, which research shows can promote positive cognitive outcomes.

- Embrace imperfection: For Gold, dramatically reducing her daughter’s screen time has taught her to be more okay with “imperfection” as a parent, like not always having a tidy home.

- Model healthy habits: ”Parents have so much to do on their phones, but just be mindful that children are always watching us, so modelling healthy digital habits in a way that fits their lifestyle is important,” says Mallawaarachchi.

- Offer alternatives: If you are cutting out or reducing your kids’ screen time, make sure to frame the transition positively, by pitching an alternative activity.

- Prepare kids and offer them choices: For Ching, one of her best tips is preparing her kid for the end of screen time. Signposting properly, rather than abruptly ending a session, and offering a few options for new activities, can help reduce the dreaded “tech tantrums”.

- Be kind to yourself: Parenting is hard and time-based guidelines don’t always account for the realities of modern life. Don’t beat yourself up if your kids’ screen time is a little higher from time to time.

- Technology use does not need to be sedentary: If you are choosing to incorporate digital devices into your child’s life, consider ways they can still be active while using screens, like learning a new dance or getting out in nature and taking photos.

- Choose educational, age-appropriate content where possible.

- Bridge the real and the virtual: When coming up with non-screen based activities, think about games that might relate to some of their favourite shows or things. If they love Bluey, perhaps they could create their own comic-book episode of the show, or choreograph a dance to the theme song for KPop Demon Hunters.

Make the most of your health, relationships, fitness and nutrition with our Live Well newsletter. Get it in your inbox every Monday.

Most Viewed in Lifestyle

Loading