Only once have I seen my dad cry. He’d just said goodbye to his own dad, at the airport. The blue-green canvas shorts he was wearing made him look less than his five-foot-eight. As Mum took his hand, he looked like a little boy. At 15, suddenly I towered.

Two years later, on school camp, five or six kids sat in some kind of bonding circle. Casually enough, a girl asked me what my dad did for work. I told her he manned the Donut King in Rosebud, Victoria.

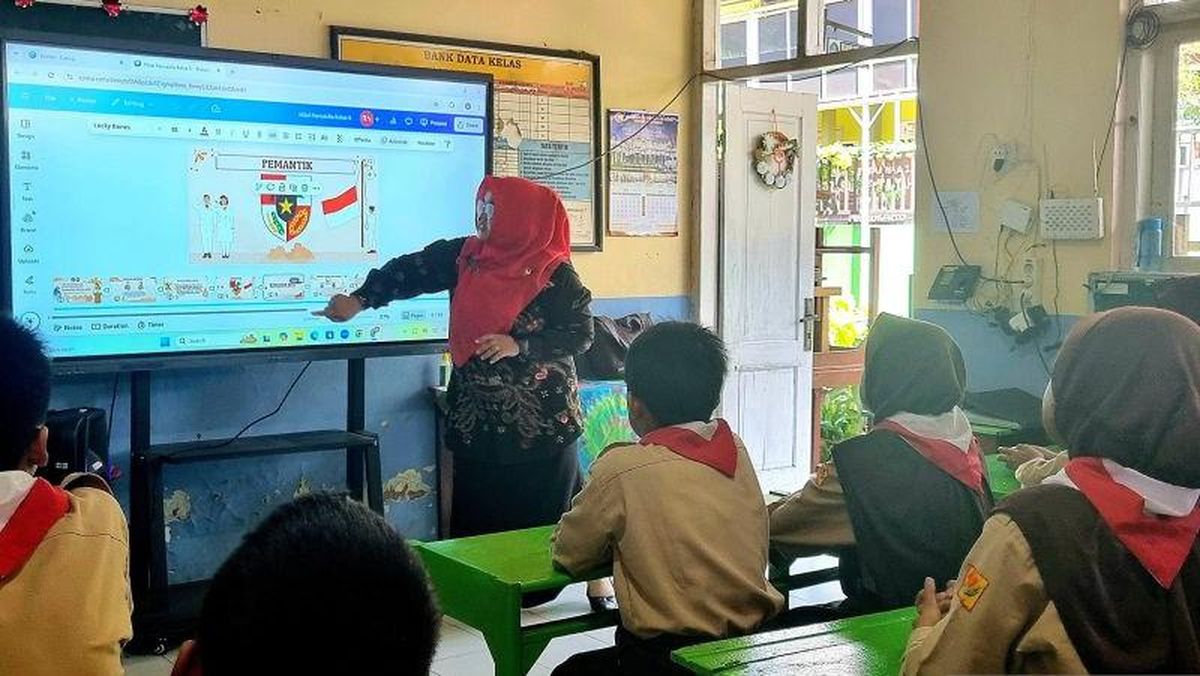

A young James Hughes with his father.

At this, another kid who knew the shopping centre expressed a kind of flabbergasted delight. “Every arvo I see this stumpy little bloke in shorts almost to his knees, sweeping up, and wonder how he does that job and what kind of thoughts bounce around his head at the end of a day,” the boy said.

Initially, I didn’t even object. The kid had a knack for blurting out blunt but mostly harmless affronts. And I was not renowned for any peacekeeping ways of my own. He persisted, as teenagers will. And I defended Dad, of course. But I didn’t exactly react with valour and pith. Who knows what to say and how to say it at 17? When you’re older, who knows when to say it and who the hell to say it to?

Donut King wasn’t Dad’s first left-turn, but he made it with his customary blend of blind gusto and black wit. Every night he came home bearing cardboard trays of experimental products: spongy stick-figures joined at the hip, bleeding jam; mini doughnuts iced traffic-light green; custard-plumped numbers as big as softballs; doughnuts shaped like dolphins.

How none of us were beach-ball-shaped is a mystery. Possibly, we’d been inoculated. Before the Donut King, Dad had worked for Big M – immunisation by strawberry milk.

When I look back on my dad’s muddled breadwinning map, I see a man who could turn his hand to anything: bookkeeping for a machinery firm; copywriting for a maker of locks and bolts; assembling refrigerated trucks; running an army barracks canteen; selling greeting cards; pasteurising; rattling around in a Cortina dragging a trailer loaded with mowers and shears and spades.

As with many fathers in that era, Dad’s weekends often included household maintenance. Why was that rubbery grey cord in the flywire door always coming loose?

JAMES HUGHESAs a Dubliner who landed in Melbourne in 1970, Dad’s never been an exemplar of sobriety. Nobody ever accused him of taking life too seriously. But he’s worked like a fiend and told a thousand ripping jokes to workmates. He showed up to all our primary school working bees, and when it was time for a beer, the other dads knew he was good for a laugh.

Junior cricket teams he coached won the most joyous premierships. I remember being in our rusty white Rover with half the team piled in, all of them thinking it was great fun going downhill – he could only stop with the help of the handbrake. For me, this was business as usual. For them, it was like being on a roller coaster with a driver cracking jokes while flicking ash out the side.

Loading

As with many fathers in that era, Dad’s weekends often included household maintenance. Why was that rubbery grey cord in the flywire door always coming loose? And why did the fence always need repairing?

Then there was the cord on the Victa; I can’t be the only one asked to give it a rip when the mower went on strike. A curiously appealing challenge, that – getting an exhausted contraption to work when stronger, calloused hands had failed. And if stubborn splutter shook to shuddery life, what a feat!

A whiff of two-stroke fuel always reminds me of Dad. In the heady days of “burning off”, he’d splash a little on the blaze. I’d stand disobediently close, loving the genie’s flare; trying to outfox the smoke, seeking a non-existent spot it wouldn’t go.

Still, in the sense-memory stakes, a sting of smoke in the eyes or a whiff of two-stroke will never touch the whiff of tomato leaves on a vine. For me, that scent is sacrosanct. In a modest garden, as well as tomatoes, Dad grew sweetcorn, silver beet, potatoes, cauliflower, carrots, pumpkin, lettuce and strawberries. All of it came to our table. I took it all for granted.

Now 84, the old man is still up at dawn. He has his senior moments – two years ago he binned a letter from Centrelink without opening it and they responded sympathetically by presuming him dead and cancelling his pension. Getting your father’s pension reinstated is a project unlikely to make anyone’s bucket list – take it from my sister, who took that thrilling adventure.

If he’s dead, nobody told him. He’s still smoking, alas. And still washing them down with moonshine concocted by another restless old character a few houses away. Dad does the bloke’s gardening, and in return receives whisky. What will life be like when all these resourceful, shambolic old men are gone?

I’ve seen dad cry just once. Doesn’t mean he hasn’t cried his share. His marriage to Mum ended just weeks before their 20th wedding anniversary. That was the year he took a shot at running Donut King. I remember he smelled of cinnamon sugar.

Get the best of Sunday Life magazine delivered to your inbox every Sunday morning. Sign up here for our free newsletter.

Most Viewed in Lifestyle

Loading