On my first Father’s Day since losing Dad, the reality of becoming an orphan hits hard

I was seven years old when I first truly understood what it meant to be an orphan. The film adaptation of the Annie musical had been released and I was confronted with the unsettling reality that parents could die, leaving their children in the care of guardians or, as in the case of that curly-haired redhead, an orphanage.

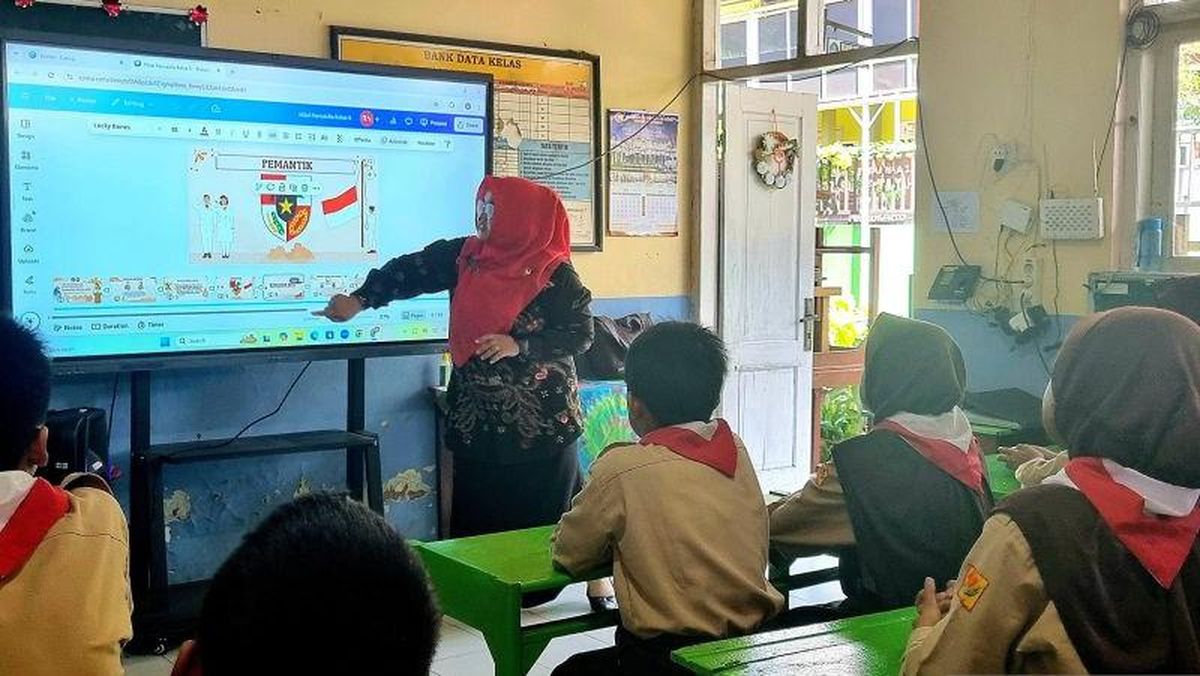

Genevieve Quigley and her father, Joe, less than two months before he died.

The idea shook me. My mum and dad were the biggest constant in my little life. How could I survive without them? Of all my early fears, it was this one that loomed the largest (even with the promise that the sun will come out tomorrow). My parents’ marriage didn’t survive my childhood, but thankfully for all our sakes they both did. It’s a good fortune not granted to all.

As they grew older, I knew it was getting closer to the time I would have to say goodbye to them. It’s the natural order of things. The alternative – the tragedy of a parent losing their child – is too devastating to contemplate. So in a sad and strange way, farewelling a parent is the goal. But logic has little to do with love and it can’t truly prepare you for the moment it actually happens.

I received the call that my darling dad had died. He’d simply fallen asleep and never woke up. He was as gentle in death as he was in life.

GENEVIEVE QUIGLEYDeep down, I’d always assumed it would be many years away. My maternal grandmother lived until age 99, so my mother was 75 before she became an orphan. I naively thought I’d be bestowed the same privilege. But when cancer took my mum just a few years after her own died, I found the odds were no longer in my favour. What was going for me was the health and vitality of my father. Even in his late 80s, he was living life to the fullest.

Loading

Then, six months ago, it happened. I received the call that my darling dad had died suddenly. No warning. No time to say goodbye. He’d simply fallen asleep and never woke up. He was as gentle in death as he was in life.

At 49 years old, with two grown-up children of my own, I was now an orphan. According to the official definition, you have to be under 18 to wear the title, but in that moment I felt seven years old again.

There is something profoundly unmooring about losing both parents. It feels like living in a house where the roof has been torn off. The walls are still standing but there’s nothing above. You feel exposed and left to navigate a world that suddenly feels much bigger – and emptier.

Of course I’m far from alone in this experience, but out of all the fellow adult orphans out there, no one understands my feelings as much as the one other person who has suffered the exact same loss as me: my sister. Even in our grief, we are struck by how many people have pointed out our new orphan status; a special shout out to the person who texted my sister, “You ate an orphan now.” (Damn you, autocorrect.) And as others remind us – perhaps a little too bluntly – with both our parents gone, we are next in line. They’re not wrong. With the roof gone, we’re suddenly closer to the great beyond.

The author as a child with her father.

In the last few months I found myself wanting to call my dad just to hear his voice, ask him a question, share my results in the Good Weekend quiz (he rarely scored below 20 out of 25) and, today, wish him a happy Father’s Day. The realisation that I never will again feels like being winded. My mother died almost five years ago and I still catch myself thinking, “I’ll call Mum.” Then, just as quickly, I remember.

Losing both parents isn’t just about missing them, it’s also about losing a sense of history. They were the keepers of so many stories: about my childhood, about our family, about themselves. Now those stories belong only to memory. So who will remind me of the things I was too young to remember? Who will answer the questions I never thought to ask?

There is also an odd sense of responsibility in the midst of the grief. Now that our parents are gone, the weight of family history now sits with my sister and me. It is up to us to pass down the stories, to share the photos and to answer the questions as best as we can.

I don’t know when this new reality will stop feeling so raw. Maybe it never does. But what I do know is that I carry my parents with me: in the love they gave me and in the way I love my own children. I guess that’s the real lesson of loss: the ones we love never really leave us. They remain in the countless ways they shaped who we are. The house still stands even without the roof. And I will keep standing, too. The sun will come out tomorrow.

Get the best of Sunday Life magazine delivered to your inbox every Sunday morning. Sign up here for our free newsletter.

Most Viewed in Lifestyle

Loading