In 1982, a young couple who had parked their car at the edge of a wood were shot through the car window. It was the eighth couple killing committed by an unknown serial killer known to the Italian public as “the Monster of Florence”. Some of the female victims were mutilated, indicating these were crimes of misogyny, but the Monster also killed a male couple: young German tourists shot in their campervan. What was beyond doubt was that they were all shot with the same weapon: a .22 Beretta.

Theories about the culprit continue to be debated to this day, but the creators of the four-part series called The Monster of Florence, Leonardo Fasoli and Stefano Sollima, were not interested in arguing a thesis or solving the mystery. “To recount [events] with honesty, respect and rigour must still carry meaning,” Sollima writes in his director’s notes. “Not to solve, not to explain, but simply to remember.” Delivering answers, he says when we meet, isn’t the point. “As a viewer myself, I prefer to see something that makes my mind ask questions.”

Francesca Olia as Barbara Locci in The Monster of Florence.

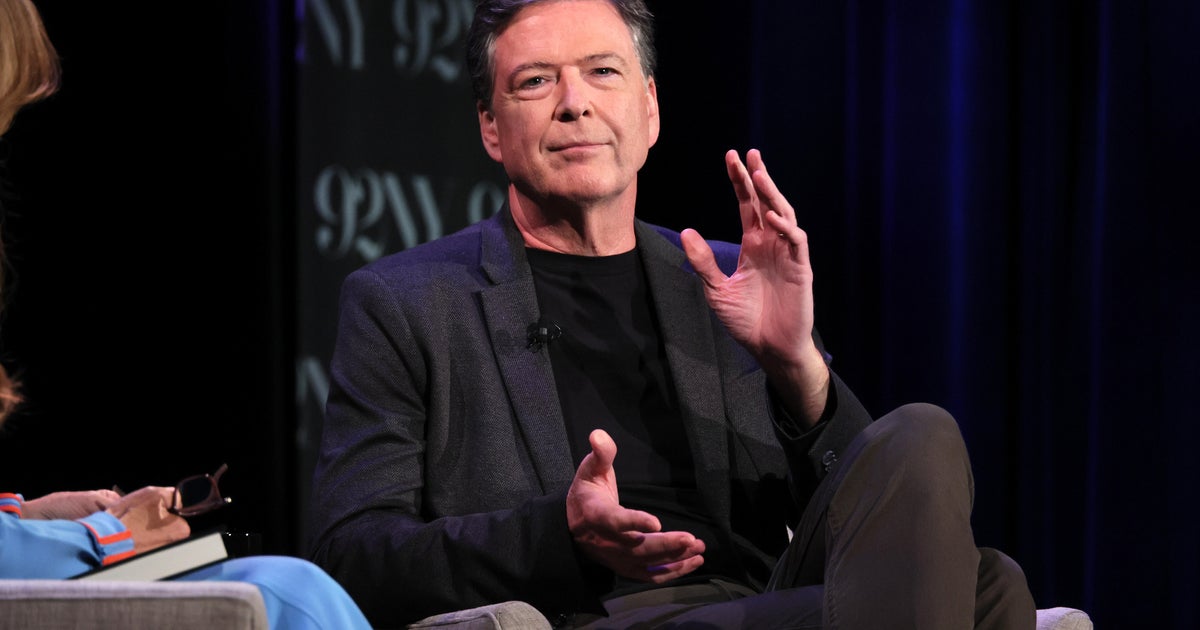

Sollima previously produced and was lead director on the long-running series Gomorrah, based on Roberto Saviano’s study of kids who sign up to organised crime in Naples. What struck him and his writing partner Fasoli about the story of the Monster, who apparently claimed his first victims in 1968, was what the case revealed about the society in which these murders could happen.

Loading

For Fasoli, it was a way to discuss a patriarchal culture that is associated with traditional village life, but remains entrenched. “There is a sort of co-existence of the old Italy – where this culture is predominant – and the new, where even young people still suffer from its persistence,” Fasoli says. Sollimi agrees. “Every day in the last year there is a woman killed, so this cultural mentality, where women are considered as objects, is still strong,” he says.

In many places, that machismo is woven into the regional identity. “If you go to Catania for example, it is a city with the symbol of an elephant,” says Fasoli. The Fontana Dell’ Elefante was built in the early 18th century in Catania’s Piazza del Duomo. “That elephant has testicles showing outside, which is not the case for real elephants. That elephant is the way it is because of Sicily’s sexist culture over the years. And it’s still there.”

After a prologue showing the most recent shooting, the story returns to 1959 in a scene that is dramatic and shocking. A woman in full bridal regalia runs across a field, pursued by suited men who wrestle her to the ground. These are the men of the Mele clan; Barbara has been promised to Stefano Mele, a man so passive he simply waits for his brothers to bring her back. Later, he will wait nervously in his house while his lodger, Salvatore Vinci, rapes a screaming Barbara in the marital bed.

Marco Bullitta, as the accused Stefano Mele, in The Monster of Florence.

Barbara changed after that, he will tell the police years later; she took one lover after another, soon gaining a reputation the Mele clan regarded as a stain on their family honour. In 1968, she and her boyfriend were killed while coming home from a movie; her son was asleep in the back seat. Stefano confessed to the murder. We see that a couple of canny police officers knew he was lying, but his conviction was inevitable.

Loading

“One reason the case was never solved is that at the beginning, they never thought about the murders all being committed by the same deviant person,” says Sollima. “They thought only about murders committed out of jealousy. This is also a cultural bias. If there is a woman making love in a wood and she is killed by someone else, then you are going immediately to think the husband did it. Because she had to be punished; she had broken the rules. So for the two first murders, the investigators only thought about that.”

It wasn’t until 1982, when detectives started to join the dots between subsequent murders, that Mele was questioned again. By that time, the police have homed in on another suspect, so Mele invents some new, utterly unconvincing lies.

The four episodes of The Monster of Florence, which zip up and down between the murders and their respective periods, have been adapted from contemporary police interviews, psychologists’ analyses and other documents. The writers built profiles of the successive suspects from these sources and relate the case as it happened; they say it was sheer good luck that the unfolding story hit the beats of a thriller. “Because I think the audience takes the point of view of the investigators, who arrest people in turn and then realise they don’t have the right person,” says Sollima.

For the writers, however, the hunt was secondary. “The story is about the suspects, each of whom might or might not be the Monster, but who were all monstrous,” says Sollima. Every suspect has his story; it often feels as if it could be any or all of them. “We didn’t want to give any answers. We didn’t even want to understand it. We just wanted to tell the story.”

They roundly reject comparisons with serial killer thrillers such as David Fincher’s Zodiac. “When you tell a true story, your characters are real and therefore you cannot get inspiration from anything,” says Sollima – but nor do they see it as “true crime”.

Valentino Mannias as Salvatore and Francesca Olia as Barbara in The Monster of Florence.

“I think of true crime as journalism, whereas this is more like genre,” says Sollima.

So it is a horror story, but one told without horror tropes: the violence is never graphic and the dead bodies are merely glimpsed in the dark, blood melting into the shadows. Sollima says they thought a good deal about how to show as little as possible. They didn’t want to turn suffering into entertainment; at the same time, they didn’t want to minimise it. If anything, they wanted to shift focus.

Fasoli chips in. “I once read that [French author Guy de] Maupassant, for example, was reading the legal cases of his time for inspiration,” he says. “The same for [Russian novelist Fyodor] Dostoevsky. When a man does something wrong, this is what really interests us.”

The Monster of Florence is now streaming on Netflix.