Of the hundreds of patients Natalie Bradford cared for during the 15 years she spent as a paediatric cancer nurse, a girl named Amy from country Queensland is still stuck in her brain decades later.

“She was a real character,” Bradford remembers.

“She would always come into the outpatients and want you to colour and draw with her, [or] come around the nurse’s desk and sit at the computer and see what you were doing.”

Amy was 10 years old when she learnt her cancer was incurable.

During one visit, she posed a heartbreaking question, asking if Bradford knew that she was going to die.

“[Amy] could see that I was [taken aback] and said: ‘It’s OK. You don’t need to be sad because when I die, I’m going to become the sunburst that you see through the clouds.’

“That was a long time ago but to this day, every time I see a sunburst coming through, I think of her.”

Bradford was 17 when she started nursing in the early ’90s at the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital. After a rotation in paediatrics during her training, she knew she wanted to work with kids.

Loading

“I’ve always enjoyed children. They have such a fresh perspective on life,” she says.

“No matter how sick they were, they always brought a brightness and energy to the space.”

Once she worked a couple of shifts on the children’s cancer ward, she developed a particular interest in helping these patients.

“You saw these families in a really difficult position at a really tricky time in their life, and you see that maybe there’s something you can do as a nurse to help that,” she said.

“People go into nursing because they inherently do want to help.”

For nearly two decades, Bradford rode the highs and lows of paediatric cancer care. There were moments of satisfaction – “being part of that process where you were able to treat the cancer and it to be cured” – and times of grief, such as in Amy’s case.

“Not all children are cured of cancer. Around 15 per cent will die,” Bradford says. “And so part of the work was palliative care and supporting families when a cure wasn’t going to be an option.”

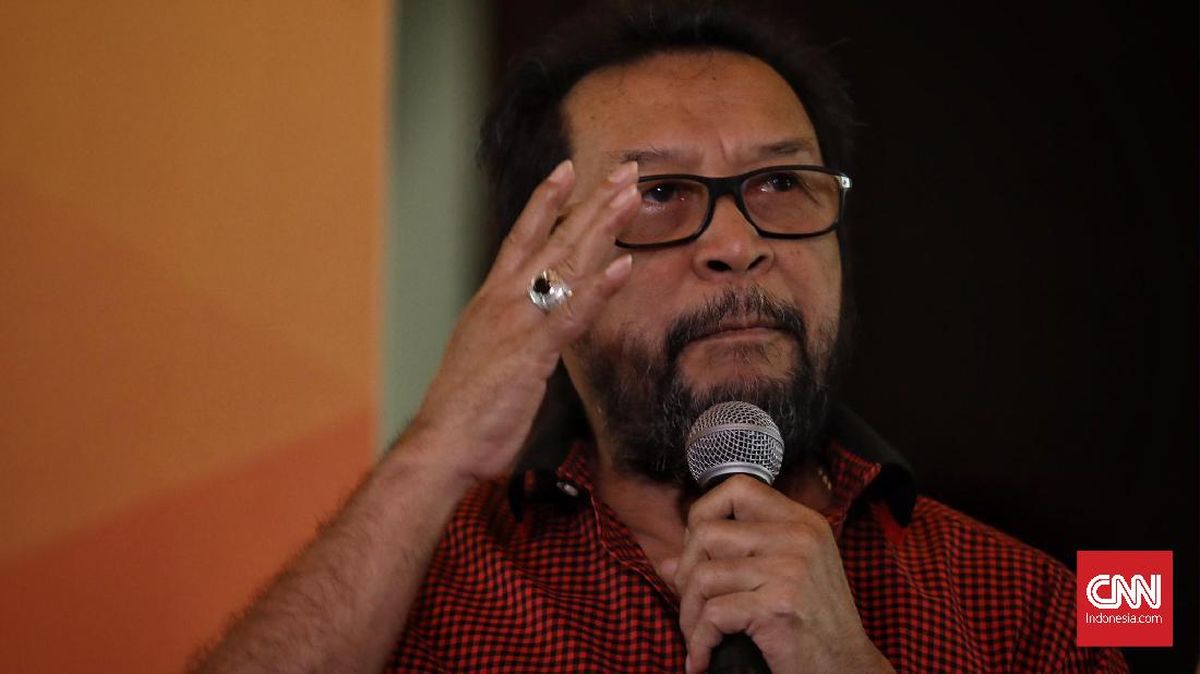

As a researcher, Dr Natalie Bradford works with young patients at the Queensland Children’s Hospital.Credit: The Kids’ Cancer Project

Amy’s family spent nine months in Brisbane after she became sick. “The impact that had on her parents and brothers and sisters, especially as she was getting sicker, [was] a reason to keep going and do what I can to improve things, where I can.”

Bradford eventually folded to the harsher realities of her work, and switched to research after nearly two decades of nursing.

“At the time, I didn’t realise that I was having symptoms of burnout,” she says. “I was processing events like they were happening to me.

“I went to the funeral of a little boy that I’d looked after and the first thing I thought was, ‘Oh, that’s the same size coffin that my son would need.’

“That’s not a helpful thing for anybody, and you’re not going to be a good nurse and support the families if you’re processing things the wrong way.”

Research allowed Bradford to stay close to the clinical work she loved. In contrast to her work in palliative care, her research over the past 20 years has focused on survivorship and the use of technology to improve care outcomes.

“I’ve always enjoyed children. No matter how sick they were, they always brought a brightness and energy to the space.”

In 2023, she received a three-year funding grant from The Kids’ Cancer Project for RECOVER, a program designed to address the long-term impacts of childhood cancer treatment.

“We know from studies in the UK, the US and through Europe that 80 per cent of childhood cancer survivors are likely to have a chronic health condition by the time they’re in their 30s and 40s,” she says.

“[Queensland Children’s Hospital] had a late effects clinic that would look at issues like fatigue or psychological problems, but the hospital closed that down.”

Queensland doesn’t have survivorship service for children after they finish cancer treatment, and the state’s $1.1 billion cancer centre planned for Herston has also been delayed by at least three years.

But Bradford is determined to continue working towards solutions for survivors of childhood cancer.

Loading

“For a long time, cancer has been treated as an acute disease … but everything else that happens after that then means that a young person might not be able to reach their full potential and contribute to society in a way they really want to.

“When somebody is diagnosed with cancer, we’ve got to start thinking right from that point onwards about what they’re going to need in survivorship.”

Start the day with a summary of the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up for our Morning Edition newsletter.