Police walk up and down streets, knock on doors and ask for the footage. Sometimes they get lucky. Sometimes no one is home.

It is the same method used since civil police forces began, knocking on doors looking for witnesses, in this case electronic ones.

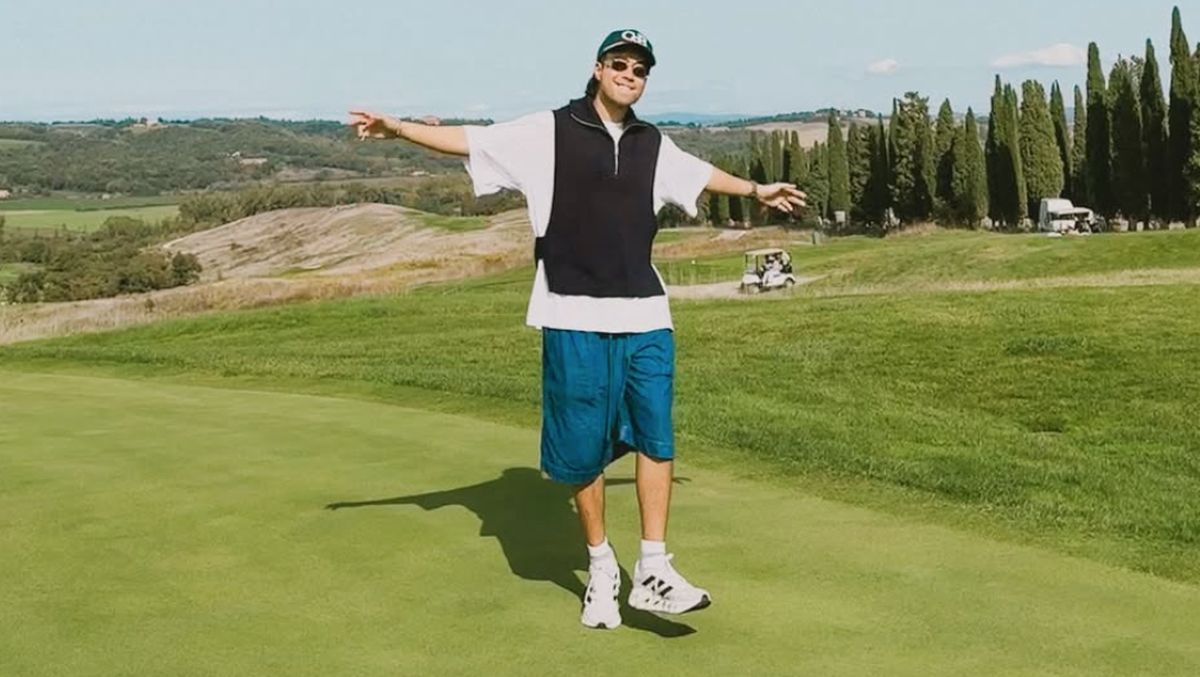

David Bartlett, founder and managing director of Safer Places Network.

If they find footage it is loaded onto the police system to be viewed by investigators.

David Bartlett is a former Victorian detective, who has used technology to expose organised crime gangs and international money-laundering gangs. He is also a Churchill fellow who became an expert at planting secret informers inside international crime cartels that needed money launderers.

The former detective believes he has a better way to capture CCTV evidence at a fraction of the cost. He says in big cities just about every major public crime is captured electronically, which means the crime rate should be going down, not up.

He uses the tragic example of the 2012 CCTV footage that captured Jill Meagher in Sydney Road, Brunswick, being stalked by her killer Adrian Ernest Bayley.

The Duchess Boutique footage that showed Adrian Bayley walking by.

“It took 85 hours to find the footage from the Duchess Boutique. We want a system that will take 85 minutes.”

He says there is an ocean of information out there, but the trouble is police are processing it through a straw.

Bartlett says there are 20 million cameras in Australia, including 8 million residential, 2 million dashcams, 3 million government and 6 million commercial.

And that does not include traffic cameras that have the capacity to be 24-hour surveillance posts.

More of that later.

Bartlett came from a hi-tech background, graduating from Swinburne University with a degree in multimedia (networks and computing).

He was settling into a career in the field when an old friend, who had joined the police, came to visit. It stirred childhood memories. When he was four, he was photographed standing proudly in a cut-down police uniform.

“As a child I always wanted to be a policeman,” David recalls, and in 2005 he joined up.

He was a general duties street cop for just a couple of years when astute bosses saw he would be a better asset if they could use his tech skills.

Because of his background he was quickly recruited in the covert intelligence area intercepting telephone conversations from organised crime figures for three years.

From there he went into counterterrorism, looking at ultra-right extremists and environmentalists with the potential to sabotage logging sites.

In 2012, he moved to the Australian Crime Commission with a brief to follow the money. It was a reverse of traditional policing where police target the crime.

Under the stunningly successful Operation Eligo, they targeted people who flew under the radar. “We would look at people with undisclosed wealth and work backwards to discover the source.”

Hand guns and drugs seized in operation Eligo.Credit: Australia Federal Police

International syndicates need to move money offshore, and they need corrupt money handlers to do it.

In Australia, there are around 6000 non-bank money movers, some honest and some not.

Eligo and sister operations identified 555 previously unknown crime figures, and charged 505 of them. It identified and disrupted 91 organised crime groups, seized $86 million, froze assets valued at $646 million, seized $1.8 billion in drugs and confiscated 80 guns.

As a result police found $3.2 million in cash in a bathtub, with another $1 million in the room. In one hotel suite they found $5.5 million carefully stacked in suitcases ready for distribution.

Money seized in 2014 after the 12-month covert operation, Eligo, by the Australian Crime Commission.Credit: Australia Federal Police

Some syndicates used new technologies such as encrypted mobile devices and the Dark Web.

Others used a system known as Halwala, an ancient Asian practice invented in the 8th century – a money swapping process based on trust.

A Middle Eastern, Indian or Asian broker connects someone who wants to move money out of Australia with someone who intends to bring cash in. The funds are swapped without being moved, leaving no internet trail from the country of origin. Bartlett recruited a network of informers, money movers who kept paper ledger records of the transactions.

One example involved more than $1 million swapped from India, picked up by a taxi driver in a McDonald’s car park and distributed in $80,000 and $100,000 lots to a series of clients.

Some syndicates buy dormant bank accounts set up by foreign students while in Australia, that are advertised on the Dark Web.

In Bartlett’s time frontmen were used to launder millions through casinos, some unaware the money was from Australian drug trafficking.

‘CCTV is now part of just about every criminal investigation, but there is no effective method of gathering it.’

David BartlettIn 2019, he returned to Victoria Police as a civilian expert to manage the IT for the surveillance and technical branch before moving into private enterprise.

But he had unfinished business in policing.

“CCTV is now part of just about every criminal investigation, but there is no effective method of gathering it.”

Loading

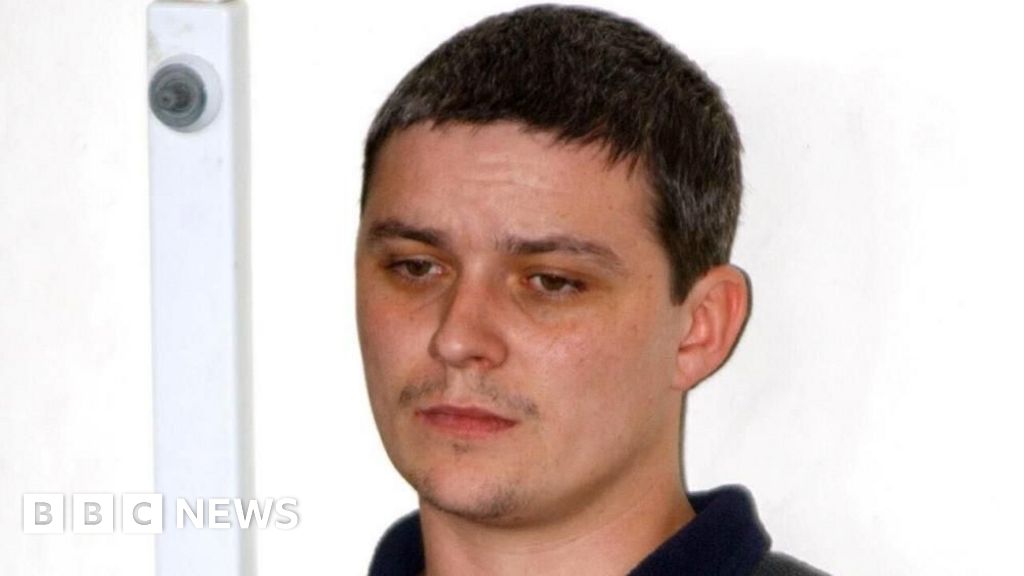

In 2015, schoolgirl Masa Vukotic was stabbed to death in a Doncaster park by Sean Christian Price.

Police at the time had no doubt if the murderer was not identified and captured, he would strike again. When footage of a suspect on a Doncaster bus was released a Justice Department caseworker recognised his tattoo.

That footage saved lives.

In an equally horrifying murder in 2018, Jaymes Todd followed young comedian Eurydice Dixon from her gig at Melbourne’s Highlander Bar more than five kilometres to Carlton’s Princes Park where she was attacked.

CCTV footage showed him stalking her from when she left the bar.

Jaymes Todd arriving at the Supreme Court for his sentencing in 2019.Credit: Joe Armao

Victoria is being battered in a crime storm with a surge of young offenders committing life-altering home invasions.

And while cameras are excellent at capturing evidence they are not deterring the crooks. (A survey of convicted burglars in Britain shows the biggest deterrence is a yappy dog.)

What Bartlett wants is a system of collecting recorded vision immediately while not giving police Big Brother powers to peek into everyone’s backyard.

The system is called the Safer Places Network and allows police to electronically request footage rather than knocking on empty doors.

Bartlett says home owners, retailers and companies will be asked to opt into a police network.

Police can log in and identify every participating camera within 500 metres of a crime scene but cannot access the footage. The camera owners are texted and emailed asking for the vision that can be downloaded into a drop box.

To be clear. They cannot access any vision without the camera owner’s permission.

“In extortions and homicides it is literally a matter of life and death,” Bartlett says.

So far, he has 23,000 cameras registered on the system with several major retailers having already joined.

Loading

He is offering Victoria Police a free six-month trial and is confident a national rollout could be federally funded.

While Victoria Police is not an official partner, a few dozen individual cops are using the platform to find registered cameras in their area.

One project discussed is to link the Melbourne City Council’s 220 Safe City cameras monitored around the clock inside a secure room in the Town Hall to police facial recognition systems to alert cops when professional shoplifters or convicted violent offenders enter Melbourne.

The investigative power of recorded vision is staggering. The journalism group Bellingcat, using open-source material, was able to prove that a Russian missile carrier was responsible for the 2014 downing of Malaysian flight MH17, killing 298 people.

Former chief commissioner Graham Ashton.Credit: Justin McManus

Former chief commissioner Graham Ashton, an adviser to the Safer Places Network, says it is “a game changer for crime prevention”.

“It allows law-abiding citizens and businesses to make the community safer. People can hook into the system to help police catch offenders before they reoffend. It really is the modern version of Neighbourhood Watch.

“David has worked hard on this to develop the program, and it would certainly make a difference.”

John Silvester lifts the lid on Australia’s criminal underworld. Subscribers can sign up to receive his Naked City newsletter every Thursday.