Thorns tore at our clothing, and the air hung hot and oppressive, thick with insects. Sharp, broken rocks made a broken ankle all too likely, despite our hiking boots.

How, we cried, was it possible for starving men, wearing only loincloths, most of them barefoot and suffering debilitating illnesses, to survive in such a place, month after unbearable month?

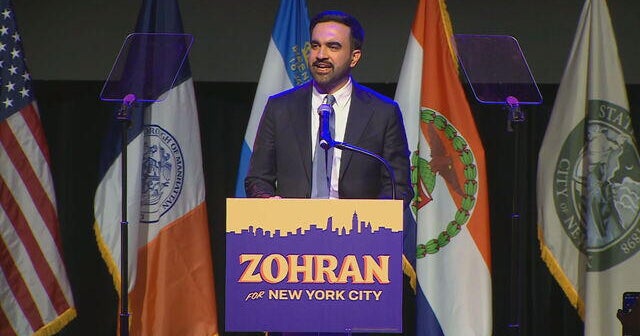

Edward “Weary” Dunlop battled to save the lives of the Australian men on the Thai-Burma Railway.Credit: Parkin Family/AWM

We were trekking in the unforgiving stone hills above the valley of the Khwae Noi river about 200 kilometres north-west of the Thai capital, Bangkok.

It was early 1987.

I was accompanied by Tim Fischer, who would become deputy prime minister in a few more years. The reason for us travelling to Thailand is a very Tim Fischer story itself.

Leading us was Ken Bradley, an Australian geologist who was planning to open up this lost place known as Hellfire Pass (also called Hammer and Tap or simply Konyu Cutting), in order that its hideous history might become accessible to ex-prisoners of war and a new generation of Australians and others.

Remembrance crosses bearing poppies at Hellfire Pass in Thailand.Credit: Kate Geraghty

I had a bit of knowledge of what the “Death Railway” meant.

I had an uncle who was all but ruined as a prisoner-of-war on the Thai-Burma railway. As a young reporter, I witnessed a man suffer a frightening emotional breakdown at a shire council meeting because the councillors were considering buying a Japanese-built pumping system. The shire president quietly explained the poor fellow had suffered torture at the hands of the Japanese on “the railway”, and requested I didn’t report the scene.

Now, stumbling through the empty Hellfire Pass and along the old track to the sites of long-disappeared wooden bridges, I needed to know more.

Loading

These years later, Australia’s biggest-selling non-fiction author and columnist of this masthead, Peter FitzSimons, has applied his distinctive style to explaining – in what I judge to be his best book – all that might be worth knowing about one POW who, through physical and moral strength and tenacious compassion, saved more of the men in his care than seems possible.

The Courageous Life of Weary Dunlop, FitzSimons has called his book, 540 pages in hardback, sub-titled “Surgeon, Prisoner-of-War, Life-Saving Leader and Legend of the Thai-Burma Railway”.

There were 106 Australian doctors captured by the Japanese in World War II, at least 44 of whom served on what became known as the “death railway”.

All of them, we can be sure, deserve a book, and FitzSimons has taken care to name all 44 doctors and the five dentists who brought mercy to the men fortunate enough to live in their self-sacrificing care.

The most famous of all remains “Weary”, a nickname given to him at university that was a play on Dunlop Tyres, whose slogan was “they never wear out”.

Sir Edward “Weary” Dunlop: depicted in Jack Chalker’s 1946 painting performing surgery in Chungkai hospital camp; visiting the Commonwealth war cemetery, in Kanchanaburi, Thailand, on Anzac Day in 1991.Credit: Fairfax Media

Much has been written about Dunlop’s immense natural leadership, of his willingness to stand between bayonets and his men, to shoulder the loads of others, to take beatings and suffer torture, all the while undertaking surgery and saving lives in almost impossible circumstances.

To many he saved, he was a secular saint. One of his men, Tom Uren, remembered for life his insistence that officers pooled the pay they received from the Japanese to buy medicines and food for the men from Thai traders. Uren passed on this collectivist wisdom to Anthony Albanese, now prime minister.

FitzSimons has used vast source material (there are 1388 footnotes in his book) to recreate Dunlop’s life from Benalla farm boy through Melbourne University (scholarships all the way), where he took up boxing and rugby and became a Wallaby, feared for his great strength and size (he stood 193 centimetres), and on to London as a young surgeon.

Then came World War II. Dunlop served as a medical officer in Greece, Crete and North Africa before sailing to Indonesia, where he was taken prisoner of the Japanese on Java.

Loading

Much of FitzSimons’ book focuses on Colonel Dunlop’s long months of 1943 as commanding officer of hundreds of men as they established slave camps at Konyu, near the Khwae Noi river, and then at what was called the Hintok Mountain Camp.

As Fischer, Bradley and I picked our way through Hellfire Pass, a lonely slash in the Thai landscape 25 metres deep and 75 metres long, cut by hand, sledgehammer, agony and death, we knew the Dunlop Force Hintok Mountain Camp had existed somewhere above us.

We could barely imagine the horror of it, which FitzSimons brings to harrowing life in his book.

Each dawn, the gaunt prisoners woke, gobbled down a few ounces of rice, scooped a little more into their pannikins for lunch and set off up the face of the mountain so steep they built a ladder from a giant teak tree.

It was a trek of six kilometres before they even began their back-breaking work at Hellfire Pass or building great wooden trestle bridges, and the same “home” before they could fall unconscious on their bamboo “beds”.

Hellfire Pass got its name because to the POW slaves, it felt like a circle of Dante’s Hell. During a killing period of frantic activity called “speedo”, they were forced to work far into the night, fires in barrels casting hideous shadows.

Dunlop used his force of will on the Japanese to try – often enough unsuccessfully – to keep the sickest of his men from such excruciating work, knowing it was a death sentence.

To collapse was to invite a merciless beating; to complain was a guarantee of a rifle butt to the face and a kicking, and to succumb to the urge to strike back meant a long period of extreme torture and slow death.

A hospital ward in Singapore showing members of the 8th Division released from the Changi POW camp, 1945.Credit: Australian War Memorial

The mere scratch of a thorn or a cut from a stone was likely to become an agonising tropical ulcer, which could lead to the amputation of a leg without anything approaching modern surgical equipment. Or worse.

Some 2800 Australians were among the 12,500 Allied POWs who died on the railway.

South-East Asian labourers suffered and died in huge numbers, estimated to be up to 100,000.

Weary Dunlop died in Melbourne on July 2, 1993. More than 10,000 people witnessed his state funeral.

Part of his ashes were interred in Hellfire Pass, and some were floated down the Khwae Noi.

- The Courageous Life of Weary Dunlop, by Peter FitzSimons; $49.99. Hachette Australia.

Start the day with a summary of the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up for our Morning Edition newsletter.

Most Viewed in World

Loading