As someone who spent a good deal of their teen years lying in the dark listening to Unknown Pleasures on high rotation (yes, my parents were worried), I could only shake my head at Opposition Leader Sussan Ley’s criticism of the prime minister’s decision to emerge from a plane wearing a Joy Division T-shirt.

In the House of Representatives on Tuesday, Ley condemned the T-shirt Albanese was photographed wearing last Thursday – the cover of the acclaimed band’s first album, released in 1979 – as he landed from his trip to the United States to meet president Donald Trump.

What did Ley say?

She claimed Albanese was “displaying the wrong values” by choosing to wear a T-shirt celebrating a band whose origins were “steeped in antisemitism”, and whose name was “taken from the wing of a Nazi concentration camp where Jewish women were forced into sexual slavery”.

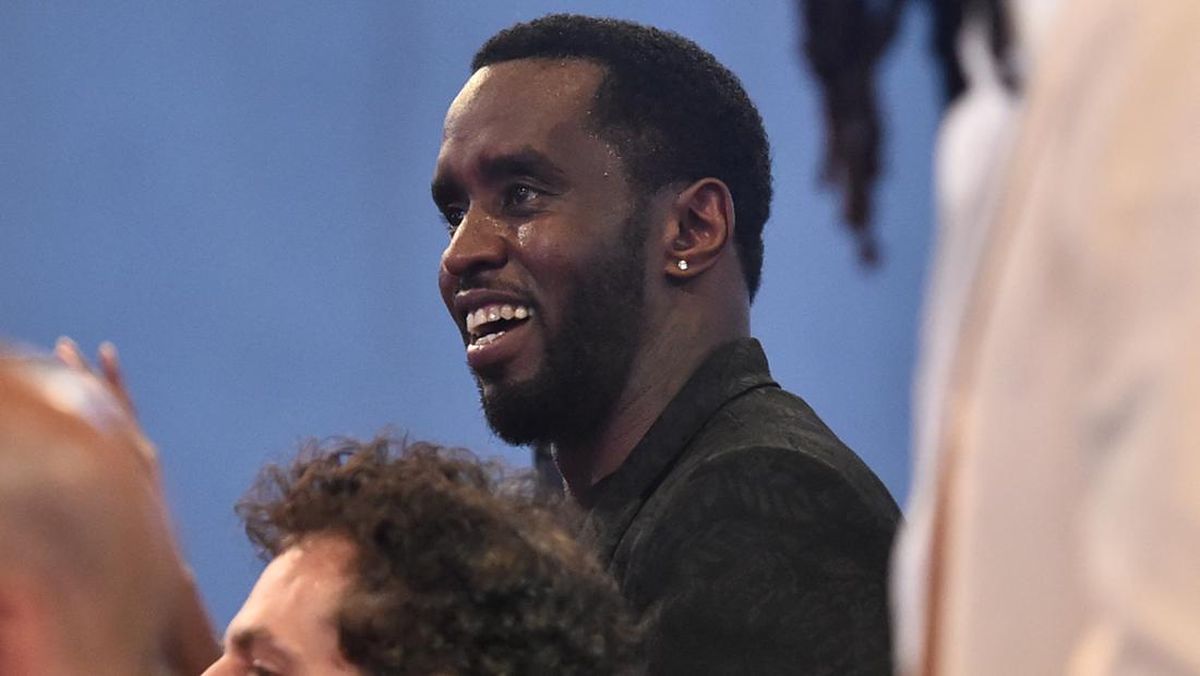

Loading

She accused the PM of choosing “to parade an image derived from hatred and suffering”, adding it was “not a slip of judgment” as he had been told three years ago about the origins of the name.

“He cannot claim ignorance,” Ley thundered. “He knew, he understood, and still he wore the T-shirt.”

It was pure political theatre, and Australian Jewish groups have noticeably declined to comment.

But does Ley have a point?

Who were Joy Division?

Joy Division emerged during the punk explosion in England in 1976, though their music is usually labelled post-punk or industrial rock. Bernard Sumner (guitar, vocals) and Peter Hook (bass) were inspired to start a band after seeing the Sex Pistols play in their hometown of Manchester in June 1976. A friend who had been at the gig signed up to play drums, and after advertising for a singer, they eventually found Ian Curtis, who would also become their lyricist.

They played their first gig under the name Warsaw (inspired by a David Bowie song from the album Low) in May 1977, supporting Manchester punk legends Buzzcocks. By August, Stephen Morris had joined on drums, and the line-up was settled. In early 1978, to avoid confusion with a London band called Warsaw Pakt, they changed their name to Joy Division.

Joy Division (from left), Stephen Morris, Peter Hook, Bernard Sumner and Ian Curtis.Credit: Kevin Cummins

They released Unknown Pleasures, their debut album, in April 1979. In March 1980, they recorded the follow-up, Closer, which was released in July; the non-album single Love Will Tear Us Apart, for which they are best known, came out in June. But by then, Curtis, who suffered from epilepsy and depression, had hung himself, bringing the Joy Division era to an end.

The three surviving members, joined by Gillian Gilbert on keyboards, would eventually re-emerge as New Order and become one of the biggest dance-rock acts of the 1980s and beyond.

Where did the name come from?

The phrase “joy division” comes from the 1953 novel House of Dolls, written by Ka-tztenik 135633, the pen name of Auschwitz survivor Yehiel De-Nur (the author’s name combines the Yiddish phrase for “concentration camp survivor” and his camp number). It tells the tale of a Jewish woman who is forced into prostitution for German soldiers in Auschwitz.

Both Sumner and Curtis were reading the book before they chose the band name, and Curtis included a spoken-word passage from it in the 1977 Warsaw song No Love Lost.

De-Nur presented his book as based on fact.

There were indeed “joy divisions” in Auschwitz and nine other camps, but the exact nature of these divisions has been debated by some historians.

What about the band’s beliefs?

Rather than the suggestion that the members of Joy Division held or hold antisemitic views, their politics, when visible, appear to lean the other way. In October 1978, Joy Division performed at a Rock Against Racism benefit in Manchester. In 1984, New Order headlined a concert in support of the striking miners in Thatcher’s Britain. The band has frequently been associated with the LGBTQ+ community and causes.

But there’s no doubt they’ve flirted with iconography associated with Nazi Germany over the years. The names Joy Division and New Order both have links to Hitler’s regime; the cover of the band’s first EP, An Ideal For Living, features a drawing of a Hitler youth banging a drum; as recently as this year, New Order included footage of divers at the 1936 Berlin Olympics from Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia during their Australian concerts.

Bernard Sumner on stage during New Order’s Australian tour in March.Credit: Ken Leanfore

In the depressed post-industrial Britain of the 1970s, imagery from World War II and the Cold War was frequently appropriated by punk and post-punk artists. It was a way of placing themselves in opposition to their parents’ generation, it had shock value, it was about liberating symbols from their supposedly “fixed meaning”, all in service of upending the old order.

Ian Curtis was certainly fascinated by the war and its horrors. In her memoir Touching From a Distance, his widow, Deborah Curtis, reflects on his fascination with Nazi imagery. But, she adds, “I think Ian’s obsession with the Nazi uniform had more to do with his interest in style itself”.

Curtis was obsessed with the darker aspects of human existence. As Deborah writes, “all Ian’s time was spent reading and thinking about human suffering”.

[The name Joy Division] didn’t mean we were Nazis or had any kind of sympathy with them, because we didn’t.

Bernard SumnerIn his own memoir, Chapter and Verse, Bernard Sumner tackles the choice of band name, describing it as an aesthetic decision.

“It didn’t mean we were Nazis or had any kind of sympathy with them, because we didn’t,” he writes, adding: “Now, in my more mature years, I probably wouldn’t pick it, because I know it would offend and hurt people, but back then, I was very young and well, selfish. Calling ourselves Joy Division was a bit mischievous.”

What about the T-shirt itself?

The image on Albanese’s T-shirt is one of the most famous and widely reproduced in all of rock music. The wavy white lines on a black background – minus any type – was the cover of the band’s Unknown Pleasures album, and created by Peter Saville, the graphic designer responsible for the vast bulk of the Factory Records catalogue (and for all of Joy Division’s and New Order’s work).

The image on the cover of Joy Division’s Unknown Pleasures is a representation of the radio waves emitted by a pulsar.

The image itself is a representation of the radio waves emitted by a pulsar, first published in a doctoral thesis by Harold D Craft Jr in 1970.

It has since gone on to be used, in licensed form and bootleg, on everything from T-shirts to coffee mugs to bed linen … even, during the COVID pandemic, on face masks.

Credit: Matt Golding

Should Albanese have worn it?

Does wearing that T-shirt constitute “an insult to all”, as Ley argued? Not at all. But was it an appropriate choice for a prime minister who has been representing this country on the world stage? That’s a little more tricky.

No matter how much Albanese and Bernard Sumner increasingly look like twins separated at birth, aesthetically, that T-shirt and dark suit pants is not a great combo.

He should feel entirely free to wear a Joy Division T-shirt at home, at the beach, or wherever he spends his leisure time, free of spurious charges of stoking antisemitism. But while he’s being PM, just a touch more gravitas might be appropriate.

Most Viewed in Culture

Loading